Mike Grant went with his dad to a doctor's visit not too long ago. Bud Grant was explaining his theories on how he had made it to his 95th birthday when he offered up something that sounded odd.

"And I chew my food," Bud told them.

"We're sitting there going, really Dad?" Mike recalled Sunday night. "He looks at me and says, 'You don't chew your food.' I said, 'How would you know if I chew my food?' He said, 'I'm an observer of men.' "

His dad used that phrase a lot in the final months of his life whenever expressing his thoughts or opinions on a particular topic. I'm an observer of men, he'd say.

Guess what?

"Now every time I eat," Mike noted, "I'm like, did I chew my food enough for what my dad thinks?"

Forever his dad, forever a coach.

“There was a lot of pressure being Bud Grant's son but there were a lot of benefits to being Bud Grant's son. There were so many positive things that it outweighed any of that pressure.”

Minnesota lost a giant with Bud Grant's death on Saturday. As a friend reminded Mike in a text later that day, "You're going to hear all about your dad and what he accomplished, but to you, he's dad."

Mike shared both tears and laughter during an hourlong conversation as he reflected on being the son of a Hall of Fame coach and legendary figure.

He followed his dad into coaching, not as a preordained career path, but as something of a secondary interest. Mike's ambition was to teach at a high school. When he landed that job, he accepted an invitation to coach multiple sports.

His dad never pushed or even encouraged him to pursue coaching. Mike says they never even discussed football when he was a kid.

"Noon game, he'd be home by 4," he said. "We had dinner on the table at 5:30 and we never talked about football or the game. Sid would be there half the time. Sid might want to talk about it, but my dad would be like, 'Sid, we don't talk about it here.' "

The sideline stoicism that made Grant so endearing to Vikings fans was ever-present at home, too. Mike can't remember his dad ever raising his voice. Never yelled at the kids, didn't use profanity. He kept his words to a minimum in the house as well.

So what made Bud laugh?

"A practical joke," Mike said. "A snake in Jerry Burns drawer at the office would make him laugh."

Apparently, Bud loved April Fools pranks.

Here's one: His daughter Laurie had a yellow canary as a pet that she kept in a cage in the kitchen. One day Bud trapped a sparrow in the garage and switched the birds.

"My sister was freaking out thinking her bird had changed colors," Mike said. "My mom probably got mad so I don't know how long he laughed."

Bud brought up that story with Mike recently. They had a good laugh remembering it.

His dad was supportive but not overbearing throughout Mike's own stellar coaching career. There were a few things that stirred a reaction though.

As a young assistant coach at Minnetonka in 1980, Mike called a quarterback sneak at the 1-yard line late in the game. The quarterback fumbled into the end zone. Bud was at the game and afterward told his son to never call a sneak from the goal line, rattling off several instances when that decision backfired in his career.

"I go, 'Dad, it would have been nice if you mentioned something before now,' " Mike recalled.

Nothing bothered Bud more than watching high school punt returners not catch the ball, allowing it to bounce and roll for extra yards. That message got relayed often to the special teams coach.

"You know it travels downhill," Mike would tell his assistant. "I'm getting it from up above. We've got to catch the punts."

Mike built a dynasty at Eden Prairie with 11 state championships, so he proved himself to be a mighty fine coach as well. His last name never felt like a burden.

"There was a lot of pressure being Bud Grant's son but there were a lot of benefits to being Bud Grant's son," he said. "There were so many positive things that it outweighed any of that pressure."

He made sure to observe his father in action as a training camp ball boy during his teenage years. The way he interacted and listened to his players and never embarrassed them with his critique. Mike has tried to incorporate those qualities into his coaching method.

"The older I have become," he said, "the more I hear my dad's voice in things that I say."

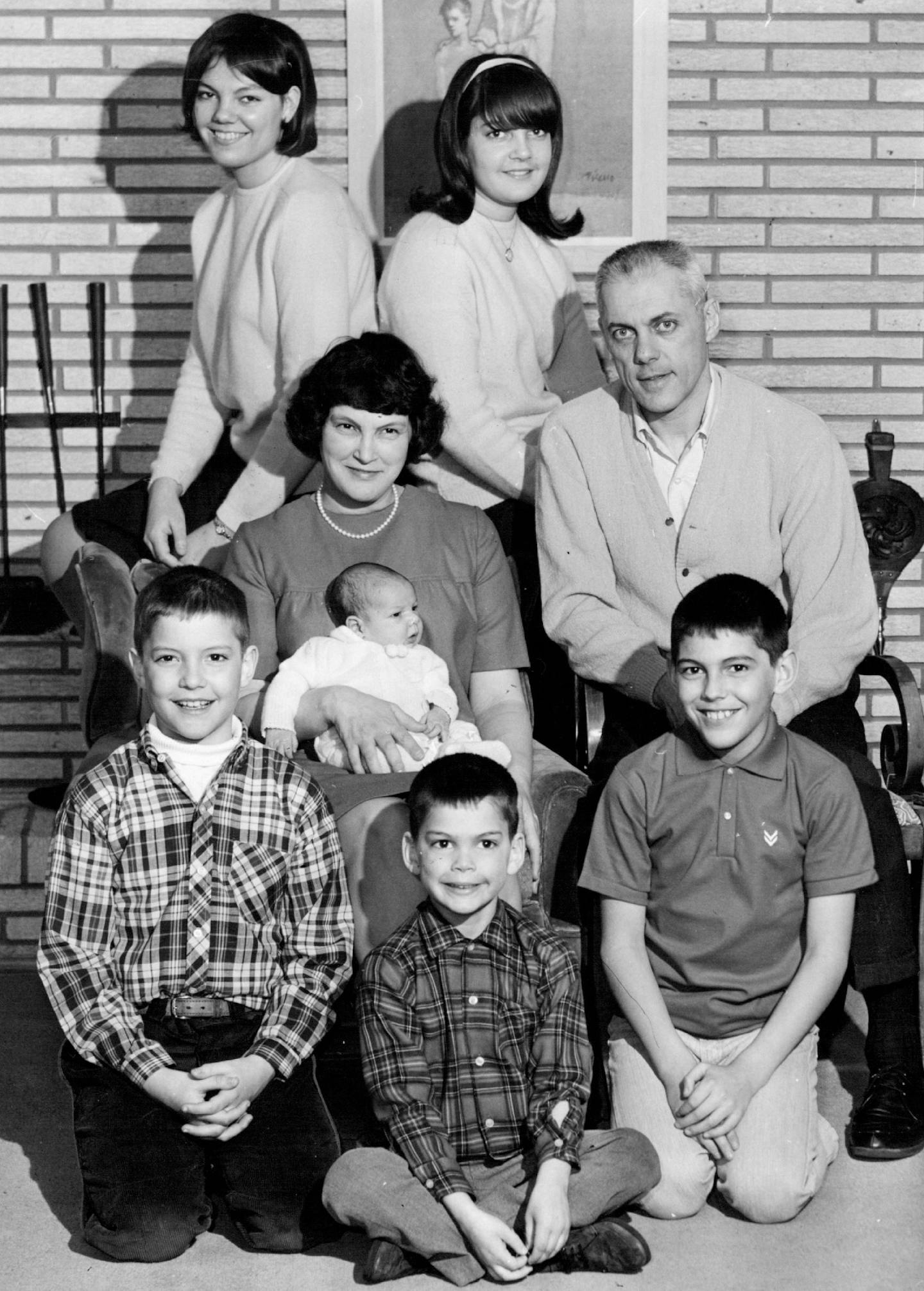

Those memories are providing him comfort right now. The fact that his dad got one final deer hunting trip last fall and a surprise gathering at his cabin over Fourth of July a few years ago. The entire family, including more than 20 grandkids and great-grandkids, pulled up at once with Bud sitting outside. He wept over that one.

As a kid, Mike didn't know his dad was capable of crying. He saw his emotions pour out all the time in his final years. Especially on Christmas Day when the whole family would visit his house. Bud loved that occasion every year.

Said Mike, "He would tell us, 'You are my best friends now.' "

Mike went to buy a copy of the paper Sunday morning. The sight of his dad's photo spread across the Star Tribune's front section made him pause.

"It showed me that he was all of Minnesota's coach," he said. "People loved him."

That realization makes him proud. That was his dad who everyone loved.