See

more of the story

See

more of the story

If it's not the end of fishing as we know it — and it might be — it's at least the beginning of a long, wavy boat ride into the unknown.

Already on some of Minnesota's best fishing lakes, boatloads of anglers are patrolling shorelines, underwater humps and other sub-surface structures, not casting or trolling, as they typically would during this prime month of Minnesota fishing.

In fact, they're not holding rods and reels at all.

Instead, with their heads down, they're watching video screens that show live images of what's going on beneath them, or ahead of them.

They might see a walleye hanging on a drop-off, or a largemouth bass lazing along a weed line . . .

Then a large muskie appears on the screen.

That's the fish we want!''

Only then do they grab their rods and reels and start "fishing.''

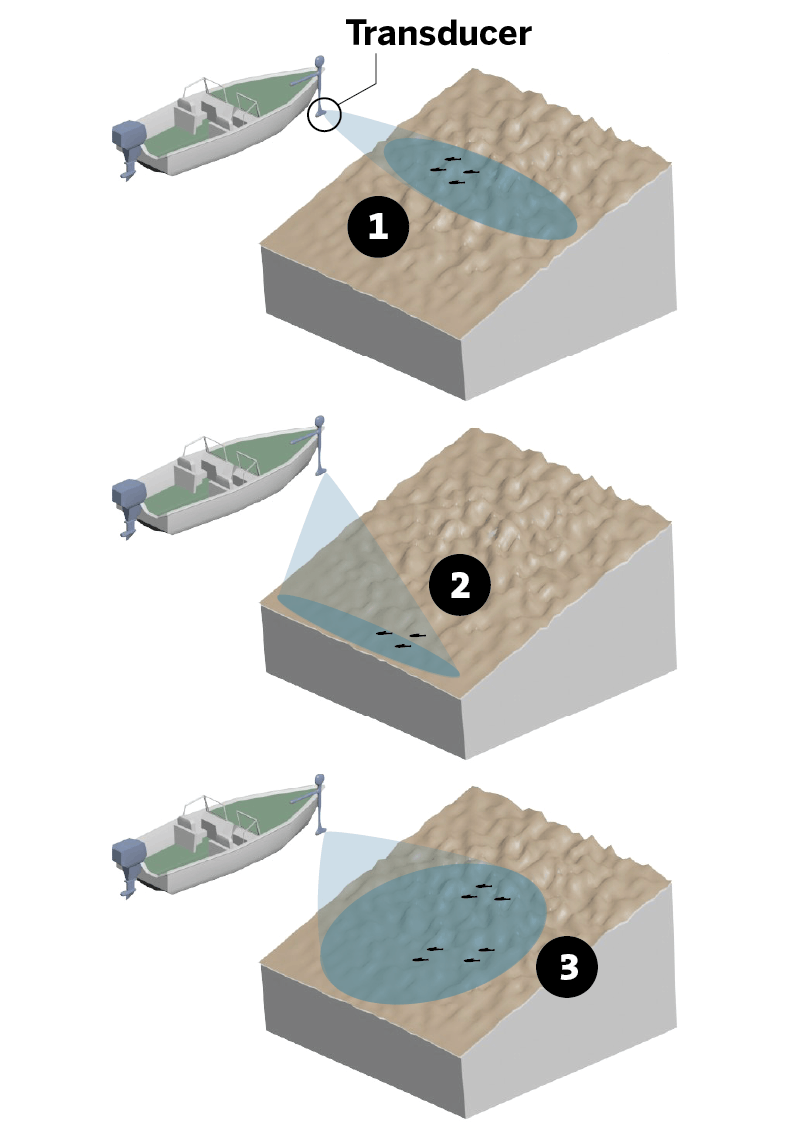

Called live sonar or forward-looking sonar, these latest angling gadgets are widely considered fishing game-changers. Easy to use, they allow anglers literally to scout a lake for the fish they want, right down to, in some cases, its weight and length, before making casts.

Real time sonar fish finder

"If you work as a team, with one guy watching the screen and the other guy with a rod and reel, you'll catch three times the number of fish you'd catch fishing the traditional way,'' said Paul Hartman, a Minnesota angler who owns the Muskie Expo held each spring in the Twin Cities.

"On live sonar, muskies show up like trucks,'' Hartman continued. "If one guy is on the graph and the other is casting, the guy on the graph can say, 'He's following your lure, pull it away,' or whatever is necessary to trigger a bite.''

Though still expensive, costing usually between $3,000 and $4,000, live sonar setups are increasingly popular in Minnesota, especially among muskie anglers, many of whom already have $75,000 or more invested in boats, motors and trailers.

Handy as the gadgets are to see below a lake's surface, they also can cause a stir on top of the water.

Sometimes boatloads of video-watching anglers cruise near and even cut off anglers who are casting to fishy looking spots as determined by more traditional methods, including time of day, water temperature and weed line locations.

"I came off the water one night last year and at the landing a couple of guys asked me why I was 'wasting' so many casts because they had already cruised the part of the lake where I was fishing and could see there were no muskies there,'' said one guide who didn't want to be named because of the growing chasm that separates "techie'' anglers from their more traditional counterparts,

"So now I'm 'wasting' casts?'' the guide asked rhetorically, "because I enjoy trying to figure out locations of muskies and how to make them bite, rather than watching a video screen all day?''

Minnesota fishing guide Tony Roach is a multi-species specialist who has used Lowrance Active Target live sonar for three summers. (Humminbird and Garmin, among others, manufacture similar units that are popular with Minnesota anglers.)

A longtime fish-conservation advocate, Roach is both fascinated by and worried about live sonar.

"Using it, I've learned a lot about fish I didn't know,'' Roach said. "One thing is how spooky fish are. Walleyes, for instance, you can see them 30 feet out, but the only time you can get on top of them is if the water is stained. If the water is clear, as soon as they hear or see the boat and motor, they're gone. So you have to hang back if you want to catch them.''

Fish can spook in winter, too, Roach said, another live-sonar lesson he learned.

"You can be watching fish, and if someone walks on the ice near your hole, oftentimes just the sound of the footsteps will spook the fish below.''

Roach worries that when live sonar prices drop, as they inevitably will, their popularity will increase dramatically — as will, possibly, their effect on Minnesota fish.

"I'm a huge advocate of technology, but when the price comes down on these things, it will change fishing 1,000 percent," he said. "I hope the DNR is on top of this and manages fish harvest as needed and doesn't react too late, saying they should have done something about this years ago."

The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is aware of the new fish-locating machines, but hasn't documented their effect, if any, on Minnesota fisheries, said the agency's fisheries chief, Brad Parsons.

"Using our creel surveys, we're trying to figure out what kind of electronics anglers are using,'' Parsons said. "Right now, these units are pretty expensive and there are not that many people who can afford them. But the prices will come down as time goes on.''

Parsons' concerns, like Roach's, extend to the machines' effects on winter fishing, for panfish particularly.

"Crappies will sometimes suspend 16 feet down or so in winter,'' he said. "People can drill one hole, look around, drill another hole and they're on the fish. This will definitely make fishing easier. I can't say yet that it's having a population effect on our fish. But if regulation changes are needed, we'll respond.''

Concerns about new fishing technology have surfaced many times before in Minnesota, beginning with the arrival here in 1968 of the Lowrance "Little Green Box'' depth finder.

Carl Lowrance himself delivered his breakthrough sonar unit to Al and Ron Lindner in Brainerd. Fantastic anglers before that time, the Lindners quickly became walleye-catching machines using Lowrance's invention.

In the years since, fishing-sonar improvements have been countless, including Humminbird's 2005 development for fishing of side imaging, a U.S. military invention dating to the late 1940s that allows anglers to see underwater up to 100 feet on either side of their boats.

"When I was first elected to the Legislature in the 1970s, as a guide myself I thought the whole fishing electronics thing had gone too far and that fish populations would be hurt,'' said retired State Sen. Bob Lessard of International Falls. "So I proposed we ban them. That idea never caught on, so instead I bought the best one I could afford for myself!''

To survive, some fish over time might learn to scatter from live sonar when it's shined on them — something Roach says he's seen already.

Perhaps, said Hartman. But until then, Minnesota fisheries can only take so much pressure.

"You can boycott live sonar or embrace it,'' Hartman said. "But if you boycott it, whether you're a casual fisherman, a guide or a competitive angler, no one is going to give you a break, or any credit for it. I don't have it in my boat, and I don't want it. But if people can afford it, most will buy it.''

The unnamed muskie guide quoted earlier agreed.

"You go on the north end of Mille Lacs and guys don't even cast anymore. They just patrol all night, looking for a muskie, and then they'll follow it and cast to it until it bites or they lose it or give up on it. It's like driving a car around until you see a deer, then getting out and shooting it. It's making zombies out of fishermen.''