Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

DULUTH – Two massive wildfires more than a century ago annihilated the landscape of northern Minnesota, killing hundreds of people and reducing entire towns to smoldering ashes.

Those fires remain among the largest disasters in state history. But a century later, wildfires like this summer's Greenwood blaze continue to threaten the North Woods. Elsewhere, fire-prone areas like California have seen historically large infernos in recent years.

Duluthian Tim Larson wondered whether the devastation from a century ago could repeat. It's been on his mind since reading "Minnesota, 1918: When Flu, Fire, and War Ravaged the State" by Star Tribune reporter Curt Brown.

"A hundred years later, we have had another pandemic as well as some [major] fires," Larson said. He sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by great reader questions.

Because Minnesota's ecosystem of boreal forests and prairie grasslands rely on occasional fires to remain healthy, it also makes them prone to large-scale wildfires. But forestry and wildfire experts said reformed logging practices, the modern landscape of rural Minnesota and better fire-response help prevent the devastation of a century ago from happening again.

Cities erased by fire

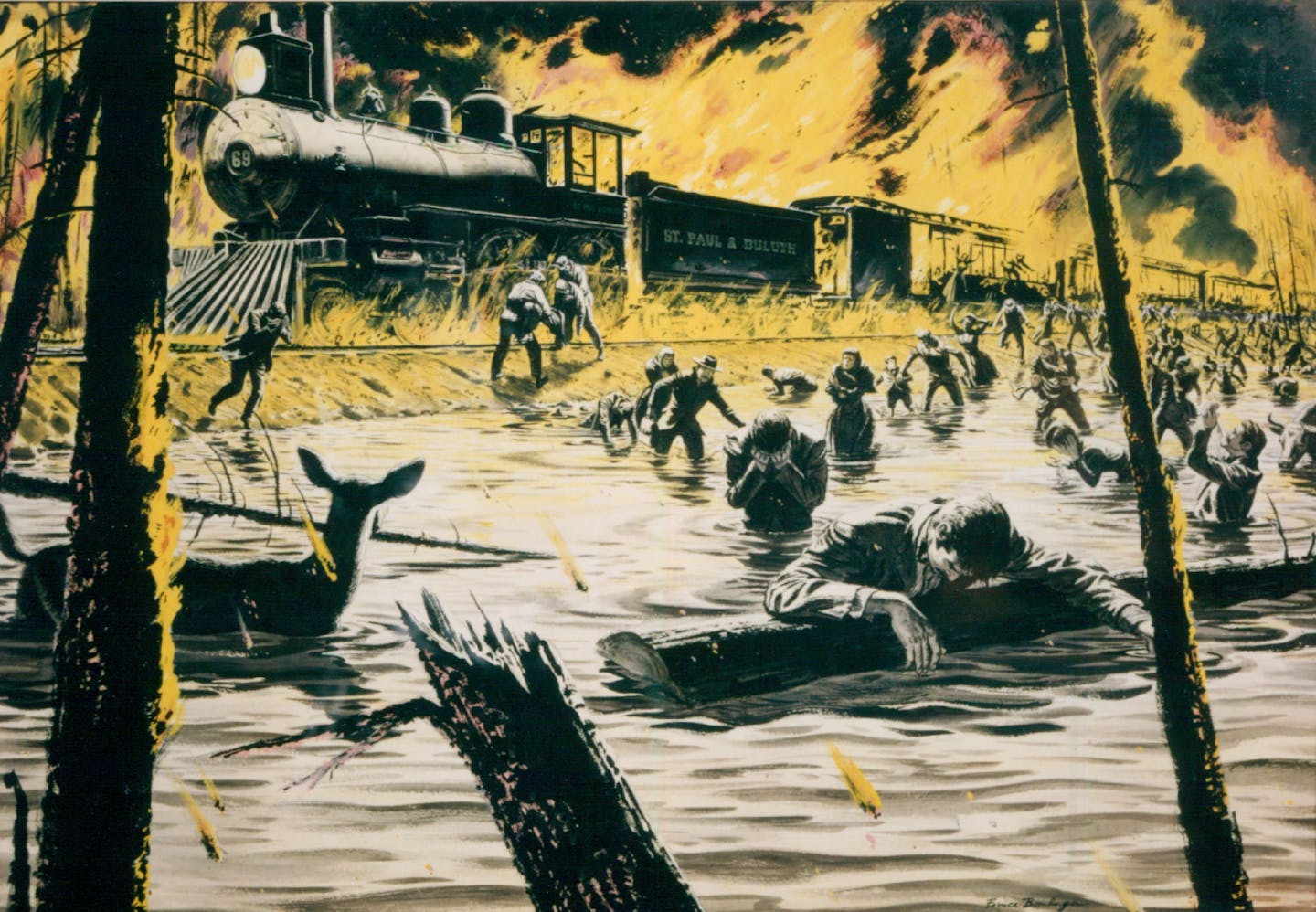

The Hinckley fire of 1894 and the Moose Lake-Cloquet fires of 1918 together burned more than 2,000 square miles — about 1.3 million acres. They killed more than 900 people, most of whom had no warning.

Only two inches of rain fell in central Minnesota the summer of the Hinckley fire. On Sept. 1, 1894, high winds turned a typical forest fire into a moving firestorm that consumed the 1,200-person logging town and surrounding areas.

Trains could barely keep ahead of the inferno. At least 418 people died, but a few survived by hunkering down in lakes and wells or a gravel pit. The death toll does not include many Native Americans who were living in the area, according to the Hinckley Fire Museum.

"Today [Hinckley] is a desert waste," the Minneapolis Tribune reported at the time. "And all that indicates that it was once an active business center is the smoking ruins, scores of horses wandering aimlessly about, and hundreds of persons, anxious and bruised and burned searching amid the multitude of dead."

The 1918 fires, which swept violently from Moose Lake to Duluth over three days, killed at least 453 people as many tried to flee on foot, horse and buggy, train or car. In Moose Lake, dozens who tried driving to escape the 65 mile-per-hour blaze died when smoke obscured a curve in a road.

More than 40 towns or villages were damaged or destroyed. The city of Cloquet, population 9,000, was "all but wiped out," according to an account in the Tribune. Moose Lake was "a waste of ashes."

"Over all the countryside, on highways and bypaths, near farmhouse ruins and beside railway tracks, lay blackened corpses," the Tribune reported.

Logging industry reforms

The 1894 and 1918 fires both began in the late summer, early fall during periods of low humidity, strong winds and hot temperatures; perfect conditions to brew a raging inferno.

Those conditions easily exist today, especially with a changing climate, said Allissa Reynolds, acting wildfire prevention supervisor for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

"The big difference back then is these [historical] fires followed the logging boom where 'slash' was left in the woods," she said, referring to the tops, limbs and branches that loggers once abandoned on the forest floor.

Trees also weren't replanted by timber barons, who quickly harvested lumber to "build the great cities of the Midwest," said John DuPlissis, silviculture research program manager at the University of Minnesota Duluth's Natural Resources Research Institute.

When a coal-burning rail car sparked the 1918 fire, that forest slash helped the fire grow rapidly as it merged with other fires and ravaged northeastern Minnesota.

Practices began to change in the 1920s, and logging companies today make use of entire trees. Now the bigger worry is drought and large stands of trees killed off by spruce budworm and emerald ash borer.

"That stuff burns very easily," DuPlissis said. All it takes is a tossed cigarette butt or errant firework to spark a wildfire, he added.

Modern fire response

Kyle Gill, forest manager and research coordinator of the Cloquet Forestry Center, said that rural population centers today have fragmented forests, major openings in woodland areas for power lines, roads and buildings, as well as less fuel lying around. Those factors inhibit fires from growing hot enough to create their own weather and jump open spaces.

The same is not true for areas like the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, a portion of which saw severe fire damage this summer. It's also why California and other western states experience such enormous fires; greater expanses of land with no breaks in flammable brush and dead trees (and the added problem of no monthslong snowpack).

But modern technology also helps reduce the likelihood of fires raging out of control.

Fire response and community notification is faster. Fire towers and lookouts have been replaced by aircraft, satellites and cellphones. Planes, too, help extinguish aggressive fires more quickly by dropping water or fire retardant in hard-to-reach places. Fire response now comes from a variety of agencies, including national, state and local entities.

Weather, including wind speed, is also monitored regularly for indicators of potential fire and crews know what kind of vegetation will ignite and how quickly.

"Wildland firefighting and preparedness have come a long way," said Leanne Langeberg, public information officer with the Minnesota Interagency Fire Center in Grand Rapids.

Ultimately, people play the largest part in reducing devastation. Roads and housing — if properly maintained — can work to block advancing wildfires. Keeping trees 30 or more feet from structures, reducing brush, and maintaining cut and watered grass can all prevent property loss if a fire moves through.

And heeding burning restrictions on campfires is critical, said Reynolds of the DNR.

"We, as humans, cause 98% of wildfires in Minnesota," Reynolds said. Lightning, by comparison, causes only 2%.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How did early settlers survive their first Minnesota winters?

Is Duluth the most inland seaport in North America?

What's the truth behind Minnesota's Kensington Runestone?

What was the most destructive tornado in Minnesota history?