Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

The tale of an eccentric frontier legislator thwarting an attempt to move Minnesota's capital to St. Peter is among the most famous bits of early state folklore.

It is such a well-known story, in fact, that Larry Eisenstadt remembers hearing it from a friend while living in New York in the 1970s. Eisenstadt, a Brooklyn native, was preparing to move to Minnesota at the time.

Now a longtime Minnesotan, Eisenstadt wanted to know whether the "skullduggery" he had heard about was true. It seems out of character for a state with a reputation for clean politics, he said.

"We're so clean that we kind of squeak when we walk," said Eisenstadt, who sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by great reader questions.

The short version of the story is that a legislator in the 1850s ensured St. Paul remained the capital by hiding a physical bill from the Legislature — while staying at a nearby hotel. The consensus among historians who have studied the incident is that while significant elements of this story are true, the political stunt is not what sunk the proposal to relocate the capital.

"It's a classic case of dumbing down history," said historian William Lass, a prolific chronicler of early Minnesota history. "It takes something actually quite complex and it reduces it to sort of an asininity."

The true story begins in 1849, when the U.S. Congress created the Minnesota Territory — extending westward from the state's current borders to the Missouri River in the present-day Dakotas. The act creating the territory said legislators should meet in St. Paul and decide on a "temporary seat of government," with the option to relocate the capital through a public vote.

The Territorial Legislature voted to make St. Paul the temporary capital. This was the logical choice as St. Paul was then the region's primary settlement outside of Fort Snelling, said Brian Pease, who oversees the State Capitol for the Minnesota Historical Society.

But two treaties in 1851, taking land from the Dakota people, opened the floodgates to settlement in the southern portion of Minnesota. The population of the territory grew from 6,000 to more than 172,000 by the end of the decade, when Minnesota had become a state.

"People were basically creating paper towns," Pease said. "There's nothing there, but they platted out [and said], 'Here, invest in this land.'"

Among the speculators was the St. Peter Company, which bought a lot of land in what is now St. Peter. Its first president was Territorial Gov. Willis Gorman (appointed by president Franklin Pierce), who by 1857 was a large stockholder in the firm, according to Lass' account.

Some important context: This influx of residents in the south created competing visions of Minnesota's potential state boundaries. A Republican faction favored a more horizontal shape excluding the north woods, extending west to the Missouri River in present day South Dakota.

In 1857, the Legislature began debating a bill to move the capital to St. Peter. It passed the House and the Senate (then called the "council") and nearly landed on the desk of Governor Gorman.

But a fur trader and legislator from the northeast corner of modern day North Dakota, Joseph Rolette, had other plans. Instead of finalizing the bill as chair of the engrossing committee, he left the building with the document and went into hiding.

"He was telling people, 'If anyone comes looking for me, tell them I went back to Pembina,' " Pease said, referring to Rolette's district. Various versions of the story assert he was partying and playing poker, or at a brothel, but Pease said those claims haven't been verified.

Rolette's absence temporarily derailed the legislative proceedings. Legislators requested a roll call vote, which effectively forced them to remain in the chamber until Rolette could be found. Cots and food were delivered as the call dragged on for nearly five days, according to Lass' account.

Ultimately, the legislators decided to vote on a new version of the relocation bill. It passed, despite objections, and Gorman signed it into law.

"Gorman's motivation was quite simply he was going to get rich by selling town lots in St. Peter," Lass said. Gorman was among the strong proponents of the horizontal-shaped state, Lass noted, which would have made St. Peter a more centrally located capital in relation to the population.

Gorman initiated planning for a new capitol building in St. Peter, and the burgeoning town prepared to become the center of attention.

"People were receiving some incredibly substantial financial offers for property that they owned in St. Peter," said Bob Sandeen with the Nicollet County Historical Society. "There was considerable excitement in St. Peter at the time."

But Gorman soon lost his post as governor to an appointee of incoming U.S. President James Buchanan. The May 1 deadline to relocate the capital came and went. So the St. Peter Company went to court, hoping to enforce the law.

Judge Rensselaer Nelson of the Minnesota Territorial Supreme Court ruled that the law was unconstitutional, however, because the Legislature had already chosen a temporary capital. As Congress had outlined, a public referendum was needed to relocate the capital.

Despite the ruling, Rolette quickly became a hero to the citizens of St. Paul, Pease said. The story of his political maneuver has since been passed down for generations.

"It's a great story," Pease said. "But in the end [Rolette's actions] probably didn't have a huge impact over the fate of the location of the state capital."

St. Peter is not the state's only would-be capital. A separate 19th Century effort to move the capital to Kandiyohi County persisted for decades. The state even acquired land there from the federal government for that purpose.

But the plan never materialized. It is now memorialized on a "Capitol Hill" historical marker, located off a rural road southeast of Willmar.

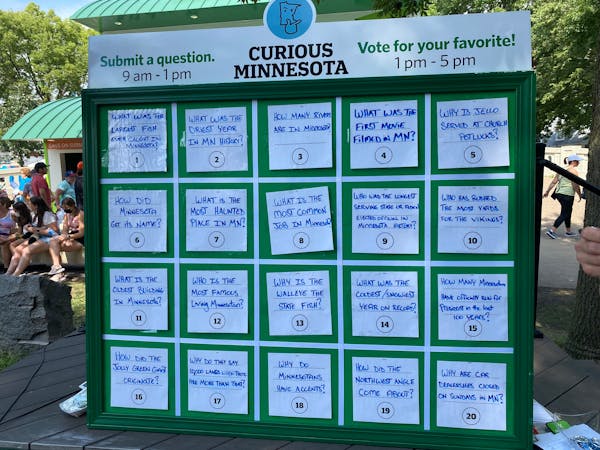

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How did Minnesota become the Gopher State?

Why does the Stone Arch Bridge cross the river at such an odd angle?

What's the truth behind Minnesota's Kensington Runestone?

Does Minn. or some other state have the best claim to Paul Bunyan?