Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

The concrete towers clad in jauntily colored panels are among the most recognizable buildings in Minneapolis — equal parts playful and severe.

The Riverside Plaza apartment complex in Cedar-Riverside is a familiar sight to many Minnesotans as a hub for the Twin Cities' thriving East African community. Beyond Minnesota, it even briefly had a national profile as Mary Richards' home on "The Mary Tyler Moore Show."

But this modernist monument was supposed to be part of something much, much larger.

These buildings, originally known as Cedar Square West, were merely the opening act of a 10-stage grand plan to radically transform the neighborhood into a self-contained city within a city.

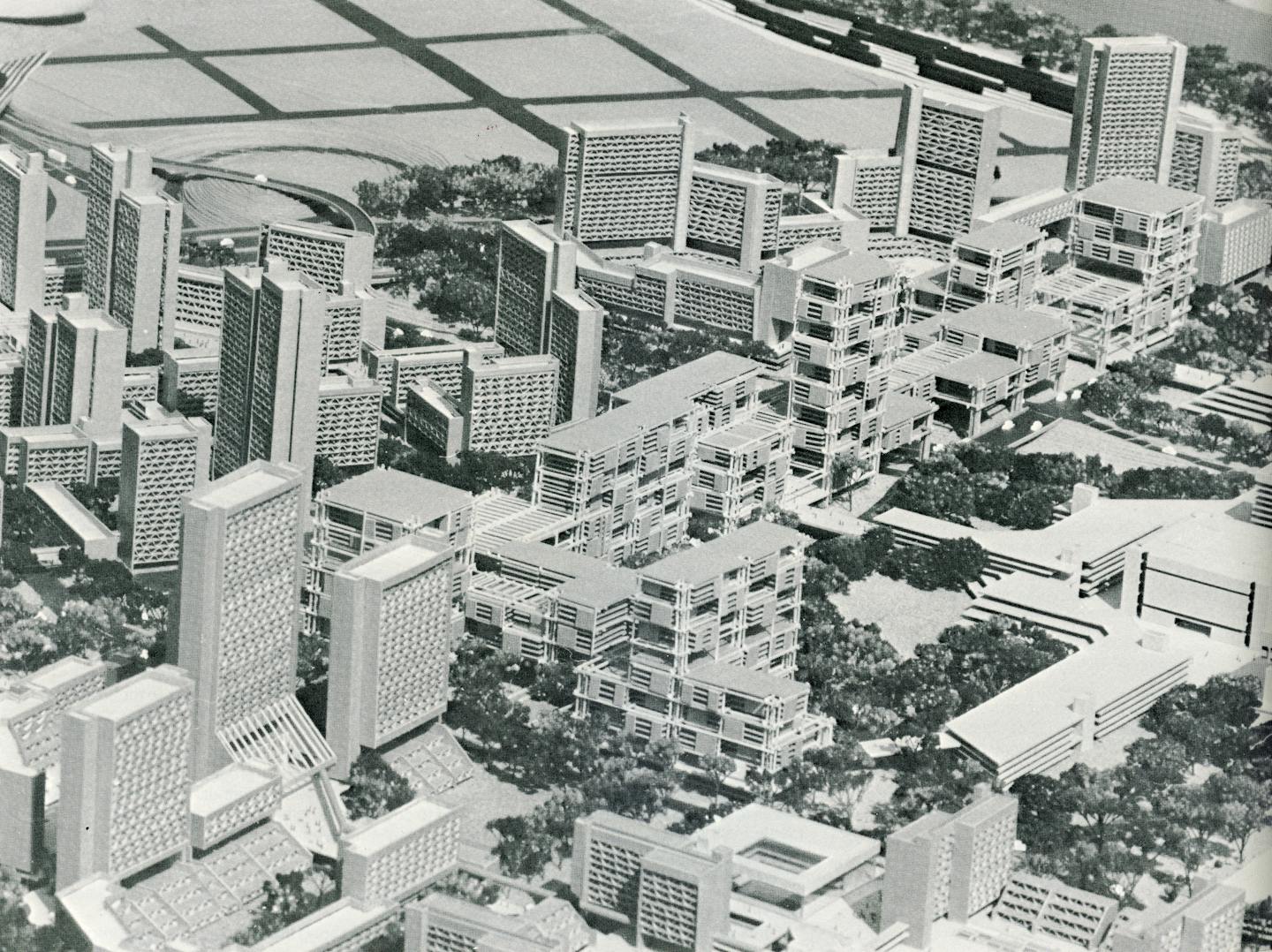

The goal was to create a diverse, integrated community peppered with urban amenities. Developers envisioned residential towers up to 40 stories high stretching across the neighborhood, linked by elevated pedestrian plazas and lined with commercial, educational and health facilities.

But as quickly as it came together, this utopian dream ground to a halt amid community opposition and troubled finances.

So, what happened?

Dave Feehan, a community activist who worked to halt the developers' plans in the 1970s, wanted the Star Tribune to tell the tumultuous tale behind the plan to reshape Cedar-Riverside. We are digging into it as part of Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

Developing a 'big vision'

They were the unlikeliest of developers. Gloria Segal was a homemaker involved in local DFL politics. Keith Heller was a University of Minnesota graduate student and business lecturer who did tax work on the side.

In 1962, Gloria Segal and her husband, Martin, were looking for a long-term investment opportunity. They asked Heller for advice.

Heller suggested the Segals buy apartments near the university, recognizing a coming demand for housing as the U expanded across the river.

Heller and Gloria Segal soon formed a real estate partnership, using loans to start buying property in Cedar-Riverside. They didn't have a lot of money, but they financed new purchases by repairing houses and remortgaging them, "sailing on inexperience and a shaky financial structure," according to a 1984 Star Tribune article.

Initially, the pair planned to build small apartment buildings among the homes they had renovated. But noted modernist architect Ralph Rapson, head of the U's architecture school, encouraged them to think bigger. By 1968, Segal and Heller's plan had grown into a full-scale transformation of Cedar-Riverside.

"My mom had a ton of energy and passion," said Gloria's daughter, Susan Segal, who is chief judge of the Minnesota Court of Appeals. "She just wanted to do something great. It was a slow evolution. But knowing my mom, it wasn't surprising that it became this big vision."

Meanwhile, the federal government had enacted new laws to subsidize new communities built from scratch, or "new towns," which were seen as a solution for endless sprawl. The Cedar-Riverside project would ultimately become the nation's first federally subsidized urban planned community — a "new town in town."

In 1969, Segal and Heller gained an ally in state Sen. Henry McKnight, who had developed the new planned community of Jonathan in present-day Chaska. McKnight brought much-needed clout and funding connections to the partnership, now called Cedar-Riverside Associates (CRA).

Community in mind

Segal and Heller felt a social responsibility toward the tenants in the buildings they owned, most of whom they knew well and saw regularly, according to author Judith Martin in her 1978 book, "Recycling the Central City."

While "urban renewal" generally meant wholesale clearing of what the city saw as blight, Segal and Heller sought to do things differently. Segal wanted "the existing community [to] be maintained and nurtured," she said in a 1970 Northwest Architect magazine interview.

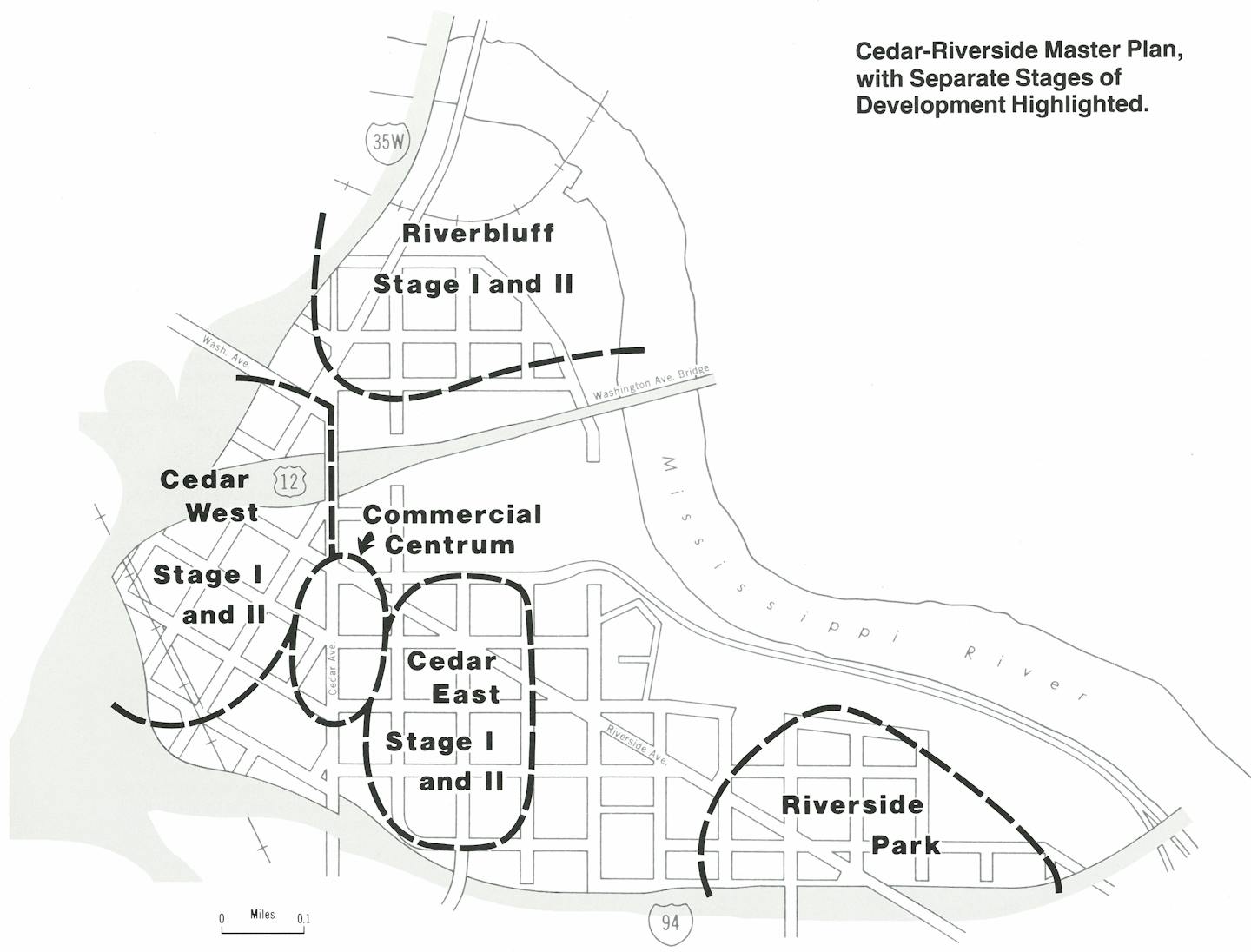

CRA soon unveiled a 20-year grand vision for Cedar-Riverside, designed by Rapson. It included 12,500 new residential units for 30,000 people, anchored by a commercial "centrum" with offices, retail and a hotel. The project would be financed in part by a $24 million federal loan.

Construction of Stage I — Cedar Square West — began in 1971 with 11 concrete buildings along Cedar Avenue. The 1,303 apartments ranged from efficiency to "semi-luxury," with the first residents arriving in April 1973.

The towers featured a novel quirk. Rapson dotted them with large, blank panels intended for residents to paint as they pleased. The federal government objected, however, fearing antiwar slogans or obscenities. As a compromise, they were painted the primary colors that appear today.

Cracks in the plan

Segal and Heller had imagined a diverse, harmonious mix of residents at Cedar Square West. But divisions appeared from the start.

First, federal housing rules forced all of the semi-luxury units into one building that included extra amenities closed to other residents. This led to the "flowering of an 'us' versus 'them' mentality within the complex," Martin wrote.

A second building housed many of the complex's residents of color, who had asked to live near people of their own race despite the developers' intentions for racial integration.

Forty percent of the complex's residents were students, so turnover was expected. But a survey of first-year tenants found that 80% of all residents planned on staying two years or less — no recipe for community building.

There was discord beyond Cedar Square West as well.

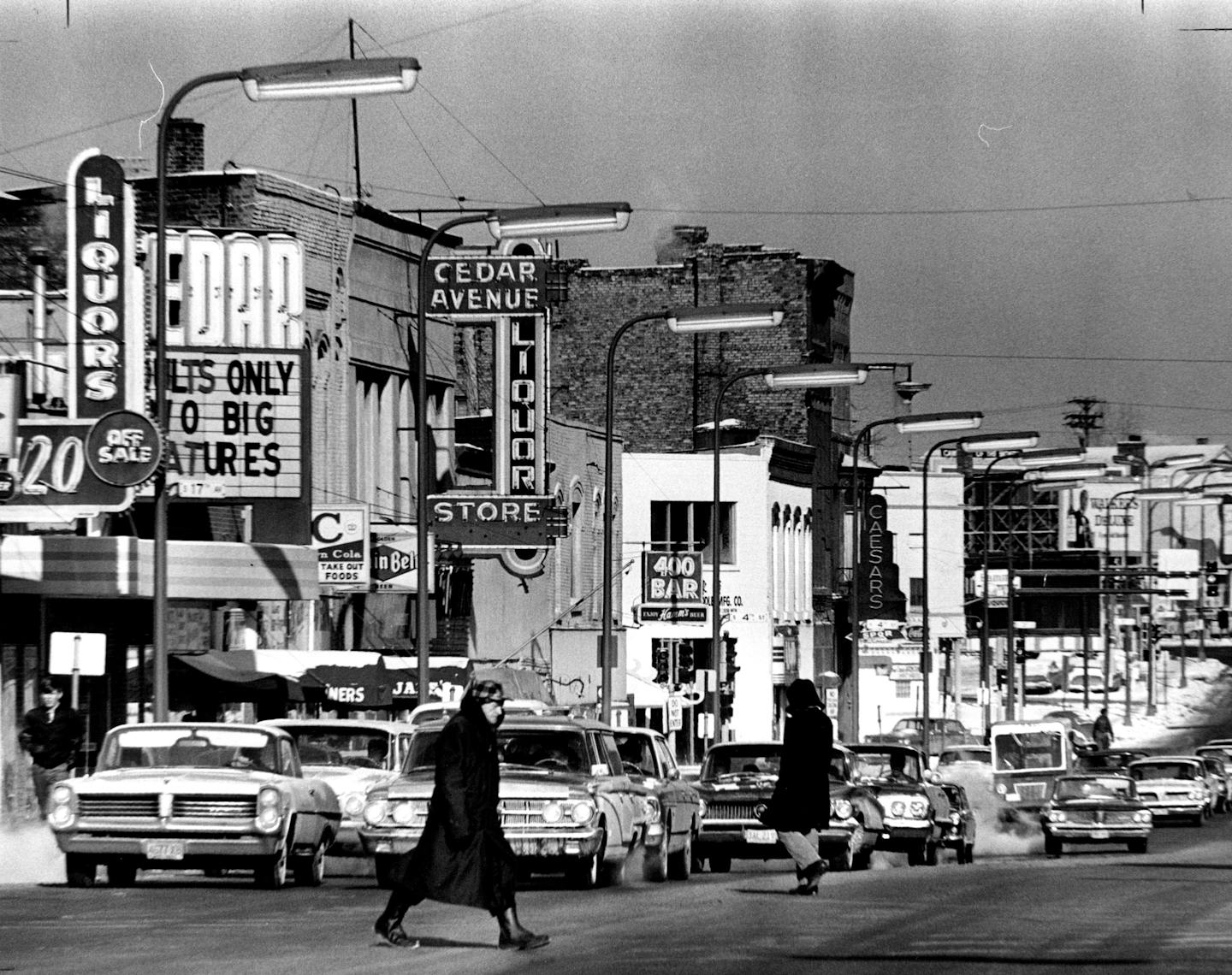

Early on, Segal and Heller had focused on rehabilitation of older buildings. Community organizers expected a plan that would preserve much of Cedar-Riverside's historic character. They were dismayed by what they saw.

Although CRA touted its vision as being on a "human scale," it was unlike anything that came before it. At 39 stories, Cedar Square West's McKnight Tower was Minnesota's third-tallest building, and it cast a long shadow over Cedar-Riverside.

"[The developers'] vision completely ignored the grassroots organizing going on," said Steve Parliament, who led the group that ultimately challenged the plan. "This was two competing visions of utopia that were diametrically opposed."

Susan Segal said her mother saw it differently. Gloria Segal was invested in the community and actively talking to people about its needs, she said. As a landlord, Gloria Segal had worked to replace saloons and adult theaters with arts organizations such as Theater in the Round and the Cedar Theater, according to her daughter.

"They were cultivating the neighborhood even as [the activists] were fighting them," Susan Segal said.

And fight, they did. Stage II of the plan, set to break ground in 1975, called for an 1,800-unit riverfront development nearby. The opposition pounced.

In December 1973, a new group called the Cedar-Riverside Environmental Defense Fund challenged plans for Stage II in court on environmental grounds, citing the effect of high-density development on social behavior, crime and children.

What ensued was a tangle of lawsuits that pitted CRA, the Defense Fund, the city and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) against one another. CRA was already operating at a deficit and having to raise rents, and the fight added to the strain. In 1974, it missed payment on its federal loan.

Gloria Segal soon resigned as vice president at CRA, leaving Heller to manage the company.

"It was emotionally very difficult for her," Susan Segal said. "She was massively depressed. But then she pulled herself together and started doing projects here and there."

Decline — and revival

With CRA's finances foundering and the government threatening foreclosure, the dream of the "new town in town" was all but dead by 1978. In the end, Cedar Square West was the sole product. For years, a pedestrian bridge extended across Cedar Avenue, ready to connect with a future Cedar Square East. Today, just a stub remains.

After years of financial troubles under Heller's management, HUD foreclosed on Cedar Square West in 1984. At this point, the federal government was on the hook for more than $35 million. It sold the complex to the city of Minneapolis in 1987, which then sold it to developers, who renamed it Riverside Plaza.

Gloria Segal went on to win a state House seat in 1982, serving until cancer forced her to resign. She died in 1993. Heller died five years later.

Riverside Plaza was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010, allowing for tax credits to help fund a $134 million renovation — including restoration of the faded colored panels to their original hues. The complex is home to a clinic and grocery store, and a school operated on the plaza until 2021.

Echoing Cedar-Riverside's early Scandinavian immigrants and a thriving Vietnamese community at Cedar Square West in the 1970s and '80s, Riverside Plaza today is home to new group of newcomers — mostly from Somalia.

That would have made Gloria Segal proud, her daughter said.

"She would have loved that it became a Somali community, and that there was a school on the plaza," Susan Segal said. "That would have made her very happy."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why is Uptown south of downtown in Minneapolis?

Why do some major Twin Cities highways not connect directly?

Why did Minneapolis tear down its biggest train station?

How did Dinkytown in Minneapolis get its name?

What is the oldest building in Minnesota?

Why do Minnesotans call them 'parking ramps' instead of 'garages'?