Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

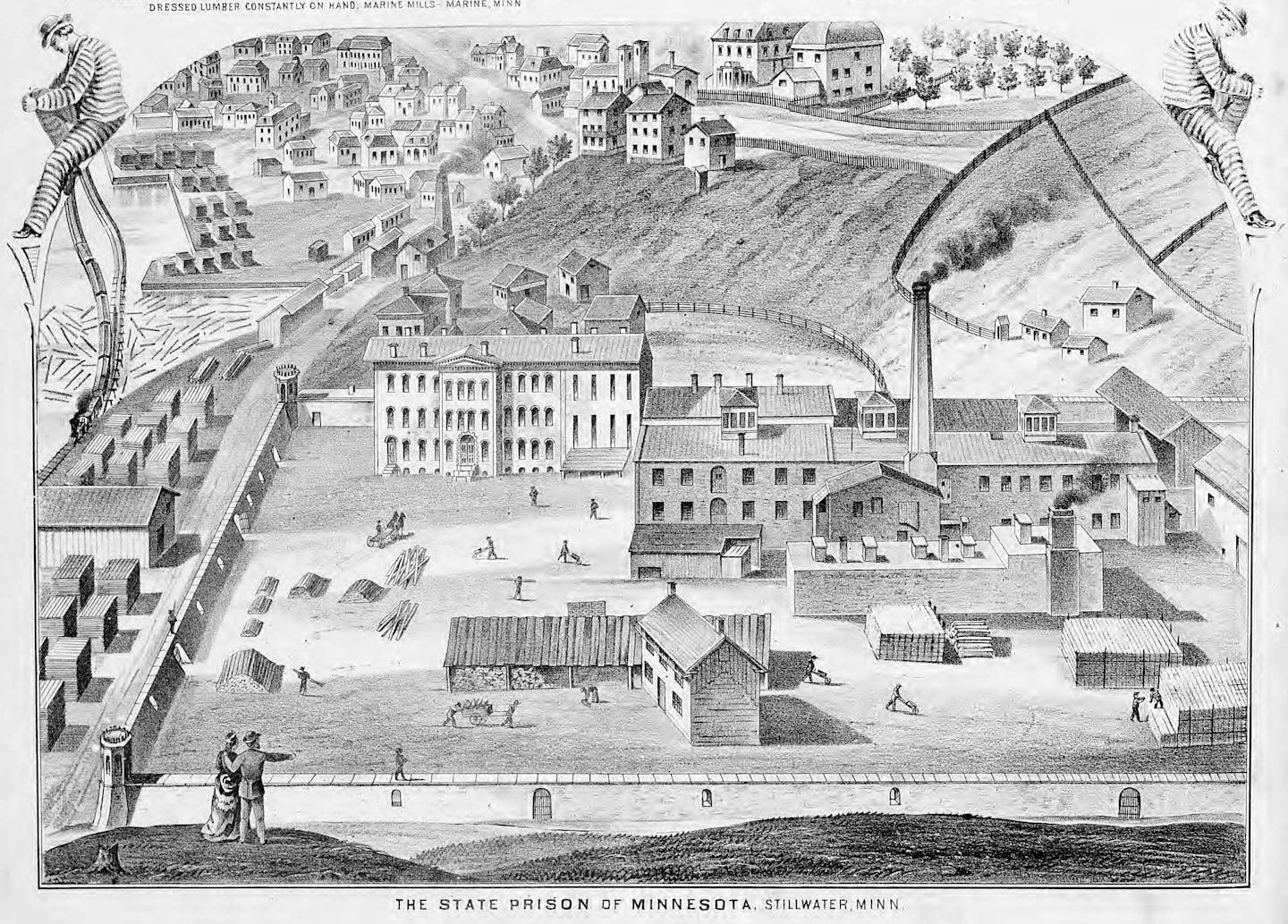

Minnesota's Department of Corrections operates 11 prisons scattered across the state, a system that traces its roots to a frontier facility in Stillwater.

A reader wrote to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project, saying he had learned in grade school that the newly formed territory of Minnesota needed a university, a capital and a prison. He was taught that Stillwater chose the prison first, and he wanted to know if that was true.

It doesn't appear that the prison's location was so neatly decided. Other locations were considered and rejected. And the sense that all three institutions were chosen simultaneously is "a myth," Washington County Historical Society executive director Brent Peterson said.

At the first meeting of the territorial Legislature in 1849, Gov. Alexander Ramsey urged leaders to lobby the federal government for money to build a lockup facility, according to a 1960 history authored by James Taylor Dunn, former chief librarian for the Minnesota Historical Society. At the time, "civilian malefactors" were held at Fort Snelling or Fort Ripley, Dunn wrote.

The settler's voices were heard, and Congress allocated $20,000 to build a prison in June 1850. But it would take several months to determine its location.

Finding a site

An early plan to place the prison in the village of St. Anthony (which later became part of Minneapolis) was roundly rejected by its residents "with the most marked contempt," Dunn quoted from the Jan. 30, 1851, edition of the Minnesota Pioneer of St. Paul.

A site farther away from populated areas was then considered, including Benton County in central Minnesota. But that was deemed too distant.

The prison site was still in play when the territorial Legislature met for the second time in 1851. Representatives from St. Paul, Stillwater and St. Anthony squared off in a bitter dispute over who would get the federal dollars flowing into the state for the creation of key public institutions, according to a 1935 history of the state, "Minnesota: the Land of Sky-Tinted Waters." An excerpt of the book, authored by Theodore Christianson, was provided to the Star Tribune by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library.

St. Paul had a distinct advantage in being named the capital. It had been designated as the site of the Minnesota Territory's first legislative assembly in 1849 by the act that created the territorial government. Still, the St. Anthony contingent wanted to move the capital upriver to their village. They lost their bid when St. Paul and Stillwater agreed to a deal: St. Paul would get the capital, and Stillwater would get the prison.

The vote was still close, according to Christianson's book.

Chagrined at their loss, the representatives from St. Anthony would eventually win another key public building project: the creation of a state university.

As for the prison's specific location on what would become N. Main Street, that was thanks to the man who would become Stillwater's first mayor, John McKusick. The owner of a sawmill with significant land holdings, McKusick sold a marshy plot ringed on three sides by cliffs to the territorial government for the prison. The spot was known as Battle Hollow because of a bloody clash there in 1839 between Dakota and Ojibwe Indians.

'A disgrace'

Using stone from nearby quarries, the Jesse Taylor Co. built a three-story prison with six cells, two dungeons, an office and a workshop. The buildings were complete by 1853, and Francis R. Delano, one of the Taylor Co. contractors, became the first warden.

But the new facility couldn't contain its inhabitants very well. The prison was notorious for escapes, with eight made in ten months in 1856.

"Their methods of escape varied," Dunn wrote. "The hall floor was pried up; an iron cell door was lifted from loosened hinges; a burglar's bar was smuggled in, according to the warden's record book, by 'unknown hands'; locks and shackles were picked; iron window bars were sawed; holes were dug through the outside wall."

The Stillwater Messenger of Feb. 10, 1858, gave it this review: "Our Penitentiary is a great humbug. There is no security about it — it is a cheat, a swindle, a disgrace."

Lawsuits followed. Indictments were brought against prison officials, but they were eventually dropped and Delano retired.

The prison relocates

Stillwater lumberman and politician Henry N. Setzer brought about reforms, which included ordering six muskets and bayonets from the state armory for use by prison guards. He also complained about the prison's location as cramped and marshy, conditions that would eventually have the state abandon the Stillwater site in 1914 and relocate the prison to its current site in Bayport, a few miles south.

Much of the original prison was torn down in 1936, but a set of factory buildings were left standing for a cordage business that had long operated within the prison. Prisoners continued to make twine there into the 1970s. A dairy operation took over and operated at the site until it was sold to Stillwater in 1996.

But disaster struck in 2002, amid plans to renovate the buildings for condominiums. A teenager who had been exploring the complex with friends started a fire, and the buildings were destroyed.

Today, the warden's house at 602 Main Street N., along with a stone wall and the base of a guard tower, is the only piece of the prison complex that remains. It is now operated as the Warden's House Museum by the Washington County Historical Society.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Did political shenanigans derail an effort to move Minnesota's capital from St. Paul?

Why is Uptown south of downtown in Minneapolis?

West, North, South, Park: Why are there so many suburbs named St. Paul?

Was Minnesota home to nuclear missiles during the Cold War?

Why do inland cities like St. Paul have so many seagulls?

Why do tiny cities like Lauderdale, Landfall, Lilydale, & Falcon Heights exist?