Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Minnesota is known for its flat prairies and rolling grasslands, but one area of the state diverges from the norm.

The awe-inspiring bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River in southeast Minnesota draw many to that region, including nature enthusiasts looking for biking trails, canoeing and hiking opportunities.

Amanda Lewandoski loves driving down Hwy. 61 and admiring the bluffs. She wondered how they came to be.

"Sometimes you can see layers on the bluffs and I'm really just curious what it all means and how long ago it all happened," she said. Lewandoski submitted the question to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by reader questions.

The short answer is that the lack of glacial activity in this corner of the state during the last Ice Age created a unique topography that was then amplified by later floods from melting glaciers elsewhere.

The great flattening

Glaciers had a large role in forming Minnesota's topography, gradually altering the landscape over millions of years.

Glaciers came and went in Minnesota over the course of many ice ages. These gargantuan masses of ice traveled slowly across the plains and reshaped the land around them, smoothing the ground like a bulldozer, according to Dylan Blumentritt, a Winona State University geoscience professor.

"They fill in the low areas, they erode from the high areas and they flatten the landscape," Blumentritt said.

But glaciers didn't touch southeast Minnesota during the latest Ice Age, more than 10,000 years ago, creating a more varied topography there.

This allowed rivers to form in what is known as Bluff Country or the Driftless Area. These rivers eventually filled with massive amounts of melted glacial ice, which etched out larger valleys throughout the Mississippi and Minnesota River system compared with other waterways throughout the state.

"As glaciation continued northward, Lake Superior became so full of melt water that sediment-free water overflowed into the Mississippi via the St. Croix River," the late Winona State biologist Calvin Fremling wrote in a 1984 report on Lake Winona. "The sediment load of the Mississippi River was thus reduced and it was able to export sediments faster than its tributaries brought them in."

Those deep cuts happened over thousands of years. Drivers like Lewandoski can see the layers of stone within the bluffs as well as the terraces, like giant steps, leading to the river. These are the result of the sediment-free water trenching the land.

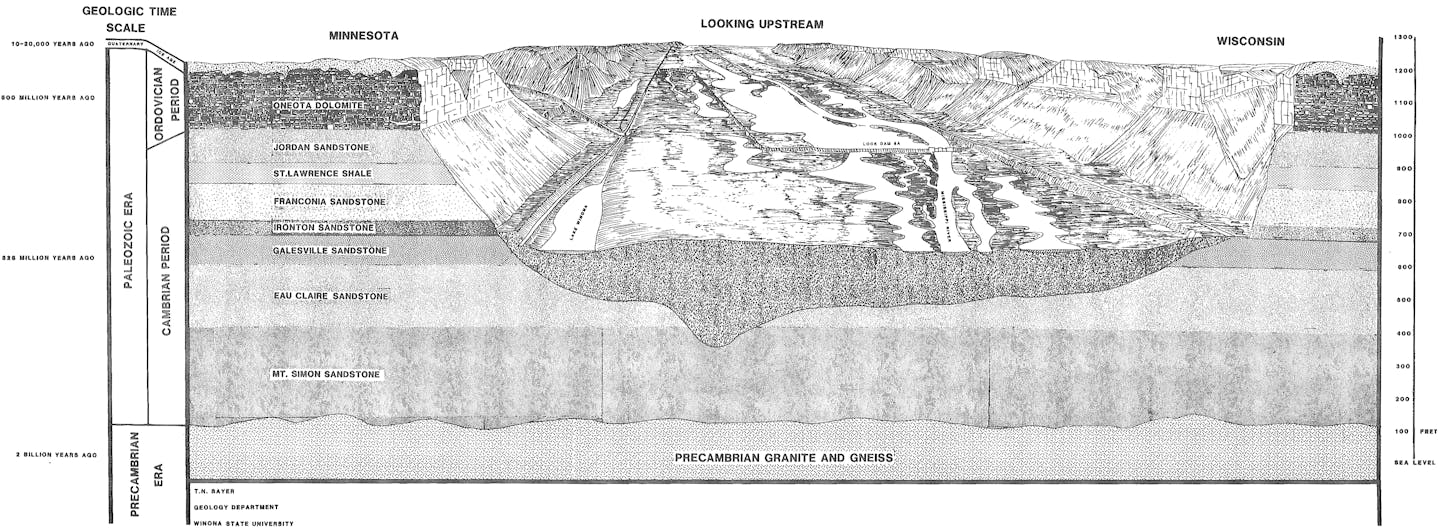

That erosion exposed layers of ancient rock.

At the bottom of the valley is sandstone from the Cambrian Period more than 500 million years ago, when the land that formed Minnesota was barren and without much plant life to hold the dirt in place. As vegetation grew and water covered and then receded from the land, different types of rock formed, leading to the shale, mudstone, dolostone and limestone that make up the bluffs.

Human-caused erosion

Natural erosion continues to shape the bluffs, but human activity has accelerated the changes. It's thought that human activity over the past 200 years has changed the structure of the bluffs at a faster pace than usual.

That started when Europeans settled Minnesota. By the 1850s, when permanent settlers came to the Driftless Area, they clear-cut trees and raised livestock on the bluffs. Pulling out the vegetation holding soil and rock in place added massive amounts of sediment to the bottom of the river valleys. That led to more pollution in the rivers, as well as more soil erosion nearby.

"We call that legacy sediment," Blumentritt said. "It's the legacy that was left behind by those settlers. They didn't know that it would have lasting effects, but it did."

Blumentritt will work with geologists at the University of Minnesota and Minnesota State University, Mankato in an upcoming study to see how settlers affected the Whitewater River Valley in the southeast part of the state — a tributary to the Mississippi.

Other geologists have studied bluffs throughout the state in recent years, in part to see how climate change and increasingly severe weather patterns are affecting the landscape.

Geologists were prompted to examine river valleys in the wake of a 2013 landslide at Lilydale Regional Park in St. Paul that killed two young students. Researchers concluded the landslide was likely caused by recent rain and soil erosion, but it led local and state officials to authorize a massive landslide study in 2018.

That study found some parts of the state, such as the Minnesota River Valley, were far more prone to landslides and geological changes because of a lack of vegetation holding the ground in place. This is exacerbated by more severe rain events due to climate change.

Which means there will be more opportunities for the bluffs to dramatically change in the future.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Who dug the sandstone caves along St. Paul's riverfront?

Is Minnesota's tiny Lake Itasca the true source of the Mississippi River?

Is it safe to swim in Twin Cities rivers, or are they all too polluted?

What did the topography of the Iron Range look like before it was mined?