Each morning, Eric Fobbe and his coworkers harness themselves into a red cylindrical cage that is then slowly lowered into a hole in the ground.

As it sinks farther beneath downtown Minneapolis, the sunlight gets swallowed up. The cage shakes as it makes it way down a metal-lined shaft into the earth, below the street, past the layer of limestone and into the sandstone below. The noise of traffic quickly dissipates and is replaced by the whirring sound of ventilated air.

Finally, about 80 feet below ground, a large cavernous room opens up. Bright white lights expose what looks like a grand building's rotunda made of light-colored sand. At the end of a short path, massive tunnels open to the left and right, big enough to accommodate a school bus. A team of workers is creating a new underground world.

"I've been down in tunnels a lot through my career here," Kevin Danen, Minneapolis sewer operations engineer, said after a recent tour of the new $57 million Central City Tunnel project. "But that one took my breath away. That was an impressive sight."

Unseen to most of the city above, crews are building a large stormwater tunnel below downtown that runs parallel to an existing one beneath Washington Avenue. Work began in September and is to be completed in June 2023.

Why are they building this?

The project is designed to alleviate flooding concerns in downtown Minneapolis.

When the current stormwater system was built in the 1930s, downtown still had homes, dirt streets and grass yards to soak up the rain. Now, concrete dominates the landscape, and some skyscrapers take up full city blocks. The extra water has nowhere to go except into the aging system.

"The tunnel system is pressurizing right now, because we're trying to put too much water in it. ... It's actually cracking the concrete," Danen said. Repairs would cost up to $600,000 annually.

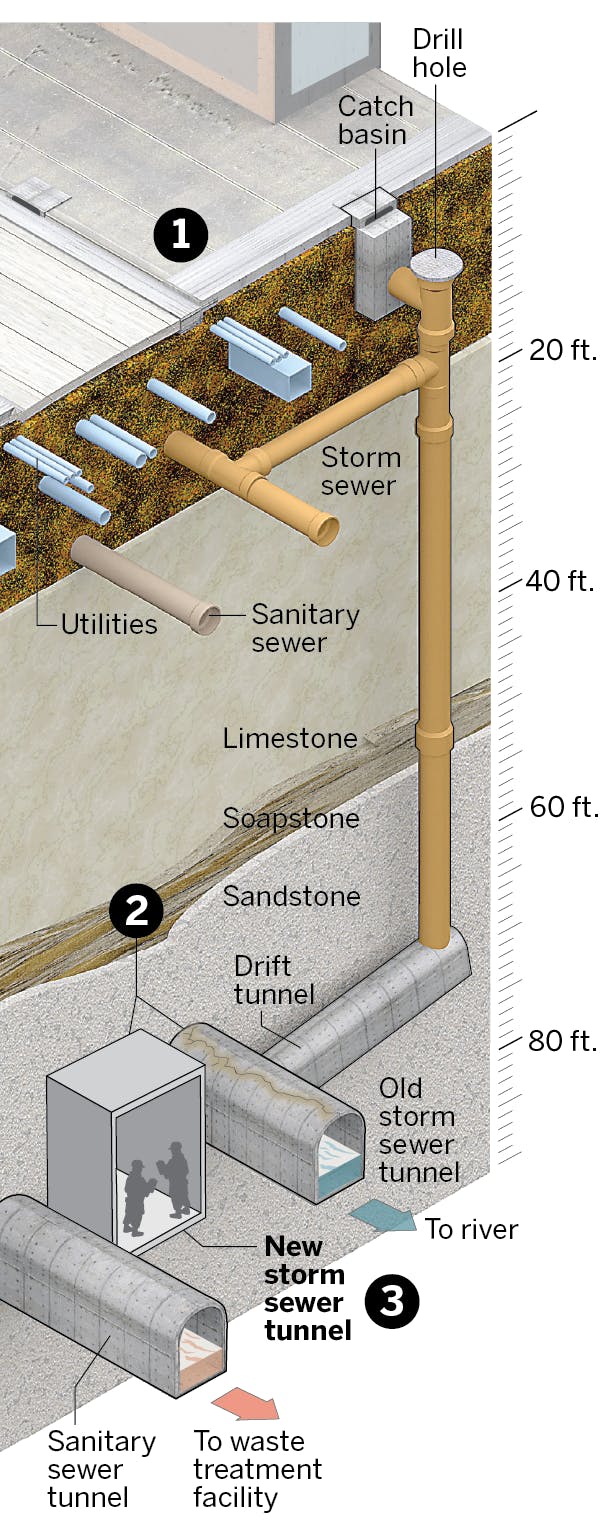

Minneapolis' storm tunnel upgrade

Beneath the streets of Minneapolis, there are 830 miles of sanitary sewers that take wastewater from homes to a treatment plant. There is also a system of more than 500 miles of storm pipes and 12 miles of deep tunnels to take rainwater from street inlets to nearby lakes or rivers. There are almost four miles of tunnels below downtown.

The current Central City Tunnel is 6 feet in diameter. When the new tunnel, which is about double that size, is complete, the two tunnels will work together.

"This is just kind of a good example of us reinvesting in our infrastructure and trying to be proactive about the changing climate conditions that we're experiencing," Danen said.

What is an average day?

The 46-year-old Fobbe, of Buffalo, has worked in tunnels for 12 years. When he goes to his job beneath Minneapolis, he has on a hard hat, face mask and googles. He uses a remote the size of a lunchbox to control a bright yellow-orange demolition robot called the Brokk. It uses grinders at the end of a long arm to knock free pieces of sandstone from the walls.

Green lasers draw the outline, so Fobbe knows what and where to grind.

His "style" is to carve out a cathedral shape to allow the sandstone to pack on top of itself at an arched point for additional support. Not all of the system being dug will have the same shape. Another tunnel portion is going into denser limestone, which can support a box shape.

Other workers use bulldozers — the size of a large lawnmower — or an excavator to clear the ground sandstone away. It has the texture of chalk or baby powder. It is eventually scooped into a tub that is lifted by a crane out of the tunnels and dumped onto the street. Workers then load it into a dump truck, taking it to a landfill or elsewhere to be reused.

The newly cleared tunnel walls are sprayed with sodium silicate to harden the sandstone overnight. Then, crews put up rebar, mesh and rock bolts to hold the sandstone in place. The work continues from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. almost every day.

The light-brown, soft sandstone is what makes this project unique for Bruce Wagener, CNA tunnel engineering consultant, who has worked on more than 300 tunnels.

"It's easier to dig but it takes a little more support just to keep it from collapsing," he said.

It is not a bad place to work, with temperatures kept at about 50 degrees — making it feel the same as a home basement. Yellow tubes run along the ceiling and up the shaft to provide ventilation.

Fresh air is exchanged every three minutes. Face masks are worn, though, to protect against breathing in toxic silica dust from the sandstone grinding.

Current progress

Construction is at the halfway point. The total Central City project covers about 4,200 feet. The new tunnel and current tunnel will connect at junction structures. Two of the four structures have been built.

Once the digging is done, workers will line the tunnels with concrete. Both tunnels will carry storm water to the Mississippi River, entering near the Stone Arch Bridge.

Weather conditions may cause a few roadblocks. In the case of heavy rain, workers will evacuate and wait for the current tunnel to flush out the water.Snowstorms could affect workers getting to the site or delay digging.

"All construction underground involves a lot more unknowns than construction above ground, because when you're working above ground, you can obviously see everything that you're dealing with," Danen said. "When you're underground things could change."

Eventually, the large machinery and other supplies underground will be lifted out through a shaft, the same way they — and the workers — got in.