The stolen SUV roared through the quiet residential streets, its teenage driver racing at 90 miles an hour before crashing through the front of a north Minneapolis home.

Police arrived quickly, guns drawn, as two girls emerged from the tangled wreckage: Debra and her cousin Arriell, both 16.

Police ordered them to the ground. Both were arrested, handcuffed, put into the back of squad cars and taken to the juvenile detention center downtown.

But after that day in April 2021, each girl experienced starkly different versions of Minnesota's juvenile justice system.

Arriell was given a rare opportunity to turn her life around. Instead of being summoned to court to face criminal charges, she attended a series of monthly sessions in which victims of car thefts and other crimes described how they were traumatized by their experiences. Free mental health counseling helped Arriell address her struggles with anxiety. She wrote several apology letters to people affected by her crimes, and emerged from the program with a clean record.

Her cousin and best friend was not offered those services because she was the driver of the stolen vehicle. Instead, prosecutors charged Debra with a series of felonies, triggering a protracted legal case that dragged on for months without resolution.

Then, just before last Christmas, Debra joined a group of teenagers who stole a car at gunpoint. Again, a high-speed chase ensued and the driver lost control and crashed, severing the vehicle in half.

This time, Debra did not survive.

Each day, Minnesota judges and prosecutors make life-altering decisions about children who break the law. Most kids end up entangled in the county court system, where their cases can drag on for months or years.

But some youth are offered an alternative, known as diversion. Instead of cycling through court hearings and meetings with probation officers, teens can access a host of rehabilitative programs meant to address the root causes of their behavior and help keep them from reoffending.

A child's future can hinge on the path that is chosen. Those who complete diversion are more likely to stay in school and less likely to commit more crimes than young people who are criminally charged.

But in Minnesota, the promise of diversion is going largely unfulfilled.

State law requires every county to have a diversion program, but Minnesota has no uniform standards for who can participate, no guidelines about what services those programs should include, and little insight into whether they are working.

Local prosecutors and probation departments have wide discretion over whether to offer a child diversion, meaning the course of juvenile justice can vary widely from one ZIP code to the next.

A youth who steals a new iPhone in Anoka County would probably face criminal charges and end up having to meet regularly with a probation officer. Swipe that phone in neighboring Ramsey County, however, and the same youth might be able to avoid the criminal justice system entirely.

"Our whole process for making decisions about who does and doesn't qualify for diversion is shortsighted," said Judge JaPaul Harris, a Ramsey County juvenile judge. "We're too focused on the offenses — and not on what's best for the child and the family."

The quality, breadth and oversight of diversion programs also vary widely, sowing confusion and undermining public support for alternatives to criminal prosecution.

Many counties do not track whether children complete diversion or go on to commit more crimes, making it impossible to know whether the programs are effective. Crime victims are often left out of the diversion process, and the organizations that operate the programs are rarely held to performance standards by the counties that hire them.

A Minnesota law requiring counties to provide regular progress reports on their diversion programs — including which kids succeed or fail — is not being enforced.

"It's justice determined by ZIP code, not fairness," said Rep. Sandra Feist, DFL-New Brighton, who has proposed legislation that would expand state oversight of youth restorative justice programs, one form of diversion. "Each county can do what it wants, which means that no one understands how restorative justice works and its power."

A more intensive approach

Kaylee, 12, glanced nervously around the room, her sneakers dangling just above the floor.

In a voice barely above a whisper, she described the day she threatened a boy with a deadly weapon. Slowly and with gentle prodding, the girl revealed details of that summer afternoon: the heated argument by the lake, the grabbing of a knife from a picnic table, and the prolonged chase and death threats. A school counselor, a community member and a probation officer listened in silence.

When she finished speaking, the head of Pine County's juvenile diversion program, Terry Fawcett, slid a blank piece of paper across the table and asked Kaylee to write her name at the center. Then he asked her to list every person who "felt bad because of what she did" that August afternoon. Soon, the names of the boy she threatened, her parents, friends, police officer, lifeguard and other witnesses to her violent behavior poured onto the empty page.

Then, at Fawcett's urging, Kaylee drew lines connecting their names to hers.

"That's a pretty good list," Fawcett said with a smile, as he reviewed her work. "Now, why do you think we had you place your name in the middle of this paper?"

Kaylee twirled her long brown hair for several minutes before answering, "Because I was the one who did it?"

"Yes, that's exactly right," Fawcett said. "And because it's important for you to take full responsibility for what happened — and to know how many people were affected by your actions."

These group dialogues have become the standard way that officials in this central Minnesota county handle children who commit crimes.

Here, young people accused of all types of offenses — from disorderly conduct to assault and sexual misconduct — can have their charges dropped if they agree to participate in a series of restorative talking circles with trained mediators. They must acknowledge the impact of their decisions and apologize to victims and community members. School administrators and social workers also work with the kids' families to help them access a host of services, from chemical dependency treatment to housing.

"The goal is to nip problems in the bud by surrounding these kids with good people — and then not letting them out of our sights," said Fawcett, a former high school football coach. "We are not afraid to take on difficult cases."

The program is popular with local judges and prosecutors in part because it is more demanding than court-imposed sanctions like probation.

Nearly 90% of the 138 young people who have completed Pine County's program since its inception six years ago did not commit further crimes in the year after they participated. Not a single participant in the county's diversion program has ended up in adult prison.

"There is a huge misunderstanding that restorative justice is a 'feel good' concept and the only way to hold kids accountable is by punishing them in court," said Pine County Attorney Reese Frederickson. "Nothing could be further from the truth. We're interested in what's going on with these kids' lives and how they're doing at school and at home — and you can't get that level of consideration in the courtroom."

Most kids not eligible

The idea of diverting kids to community programs instead of charging them in court is not new. Since 1995, Minnesota has required every county prosecutor's office in the state to establish a diversion program. The state also set forth broad goals for the programs, including minimizing crime and reducing caseload burdens on juvenile courts.

But most Minnesota counties stick with the traditional process of summoning the offending youth to court, and then turning to probation officers to supervise them.

The Hennepin County Attorney's Office has a wide array of juvenile diversion programs through 14 community-based providers. They offer mental health therapy, boxing classes, one-on-one mentorship and restorative talking circles.

Those efforts have proved successful in redirecting teens accused of low-level crimes. Data shows that fewer than 15% of kids who completed its diversion programs between 2016 and 2020 were charged with another crime within a year.

By comparison, the recidivism rate for young people charged and convicted in Hennepin County court has hovered near 40% for the past five years, records show.

The county's results mirror national trends.

An expansive study two years ago found that boys diverted after their first arrests were less likely to be arrested again, more likely to graduate from high school and have a more positive outlook on their futures than kids who had been formally charged in court. An earlier, widely cited study of 73 diversion programs across the country found that diverted youth were up to 2.5 times less likely to reoffend.

Despite this promising evidence, the share of diverted juvenile cases has fallen each of the past five years, according to federal data. In Hennepin, the state's most populous county, 25% of arrested youth are diverted from the courts, down from 35% four years ago, county records show.

Strict eligibility requirements bar most children from these services. Teens who commit carjackings, robberies and felony-level assaults are excluded, for example, even if they have no prior criminal record.

In many counties, elected officials are reluctant to expand diversion beyond petty crimes, fearing a lack of public support. Others believe leniency should be afforded only to those accused of nonviolent acts.

"Diversion, in my view, has never worked for the most serious crimes," Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman said in a recent interview. "Many of these kids, particularly the repeat offenders, need significant consequences."

In 2014, the Minneapolis Police Department rolled out a new program that diverted youth arrested for low-level crimes to one of several community-based organizations that would help them access a range of support services. More than 700 youth were referred to the program within the first few years.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota found that kids who participated were less than half as likely to reoffend than youth who went through the traditional court system.

But last year, the police sent only three dozen cases to restorative justice practitioners. Those referrals dwindled to two cases during the first six months of the year, records show.

Minneapolis Police Commander Giovanni Veliz, who oversees the department's juvenile unit, said police are seeing far fewer of the low-level crimes that would typically qualify for diversion. The departure of nearly 300 officers during the last two years also means prioritizing more serious juvenile cases like armed carjackings, department officials said.

"How can the community get behind programs that often feel random and arbitrary across the state?" said Cynthia Prosek, executive director of Restorative Justice Community Action, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit that organizes dialogues with youth and community members.

Numerous law enforcement leaders told the Star Tribune they believe in the merits of diversion, particularly to correct common "knucklehead" behavior by teenagers.

But if the offense escalates to violence, or involves a firearm, authorities agree the penalties must be more severe. "How many chances is too many before there are consequences?" said Shakopee Police Chief Jeff Tate. "If you're a 13-year-old who's filing a serial number off a gun, what is diversion going to do? There has to be some form of accountability that's equal to the facts of the case."

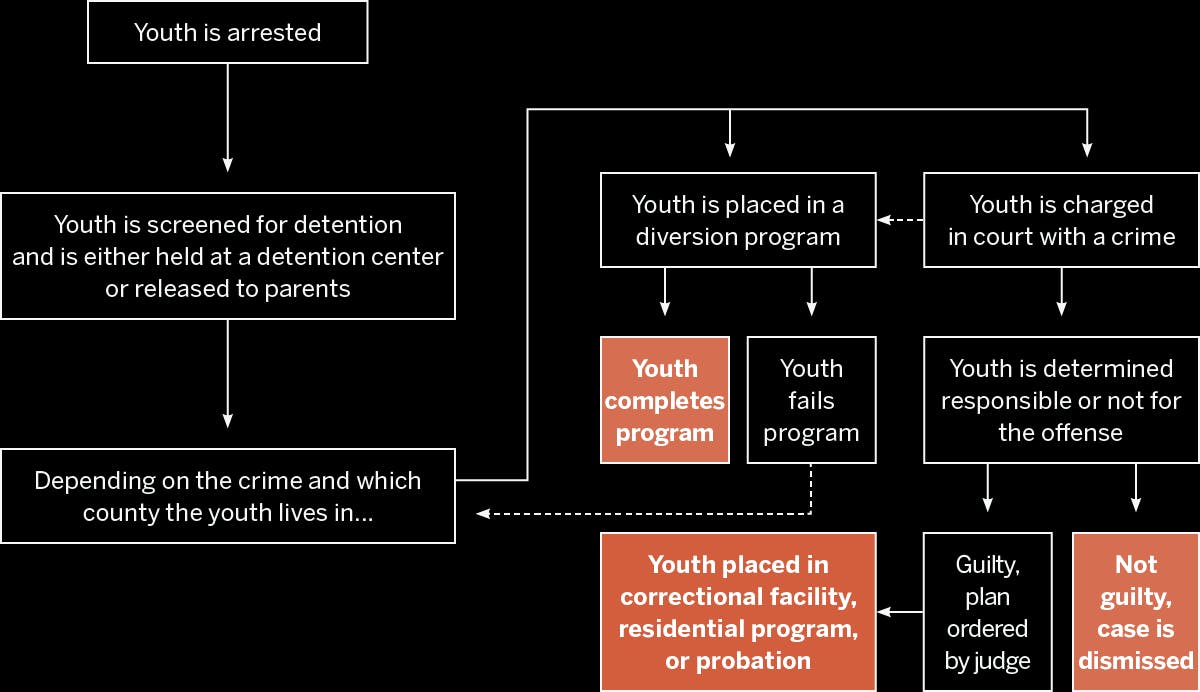

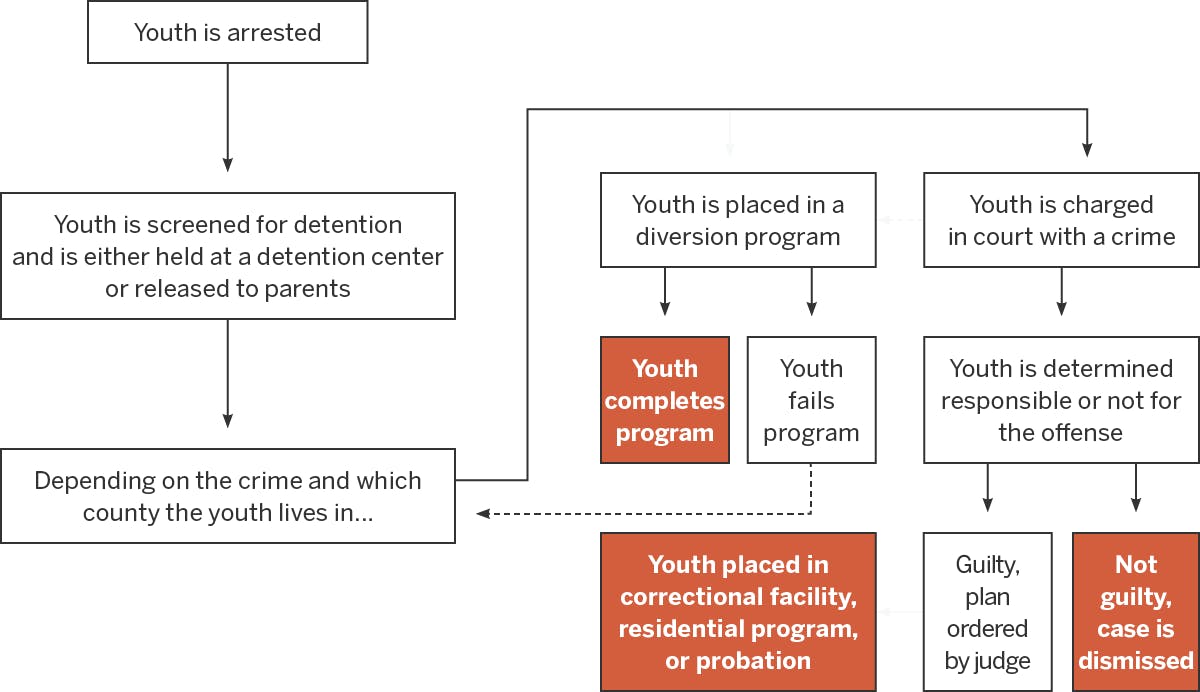

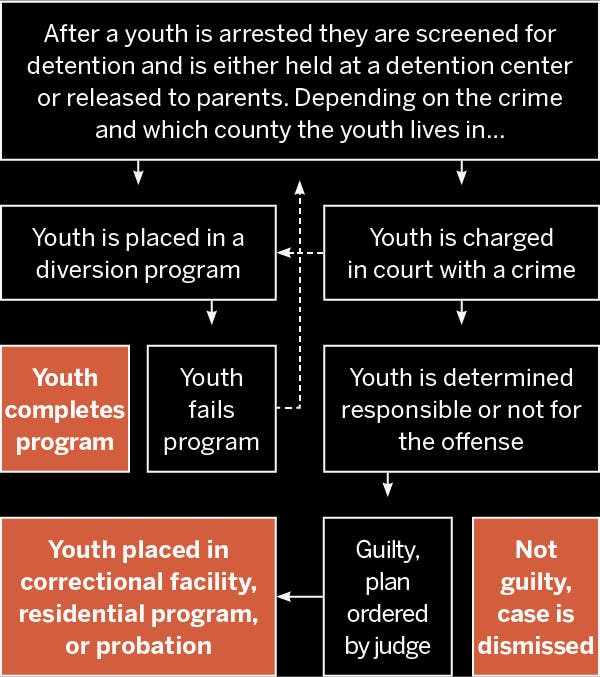

Different paths after arrest

Minnesota requires each county to have a juvenile diversion program but has no uniform standards on which children qualify. Eligibility varies by county based on the severity of the crime.

Different paths after arrest

Minnesota requires each county to have a juvenile diversion program but has no uniform standards on which children qualify. Eligibility varies by county based on the severity of the crime.

Restorative justice 'still the Wild West'

For victims of youth crime, diversion can be frustrating and opaque.

Sheila Hubbard, 71, was getting into her car one Monday morning when four teenage girls assaulted her. One jumped in the back seat and yanked on Hubbard's hair, while another repeatedly punched Hubbard before stealing her keys and wallet.

Hubbard screamed so loud — "like a wounded animal," she recalls — that a dozen neighbors chased the girls through her south Minneapolis neighborhood until they were caught by police. The assault strained Hubbard's neck and left one side of her body badly bruised.

Five months after the attack, Hubbard received a form letter from Hennepin County stating that one of her assailants, who was 12 years old, qualified for a juvenile diversion program. The letter spelled out the many benefits of diversion — that the girl would have to admit responsibility for her actions and "stay out of trouble," while receiving counseling and a variety of other support services.

To Hubbard, the idea of an alternative form of justice — one that would hold a child accountable without incarceration — sounded promising. Yet more than two years have passed since the attack and Hubbard has received no formal apology from the girls. Her requests for basic information about the status of their cases sometimes went ignored. "I never imagined this process would drag on this long," she said.

Hubbard's experience highlights another shortcoming of diversion: the quality and rigor of the programs can vary dramatically.

Some last for up to six months and offer a range of "wraparound services" such as mental therapy and mentoring. Others consist of a single Zoom session. Youth are not always required to admit guilt or make amends to victims. And children may face few consequences if they drop out of a diversion program. In Ramsey County, they can rotate in and out of diversion programs multiple times, even if they do not successfully complete them, according to the county's guidelines.

"The restorative justice movement is not in a place where it's established best practices," said Mikhail Lyubansky, a restorative justice expert and psychology professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. "It's still the Wild West."

Public skepticism about the benefits of diversion also can undermine its effectiveness.

Tamara Mattison owns a St. Paul-based organization that conducts more than 100 restorative talking circles a year under contracts with counties in the Twin Cities metro area. To her dismay, victims only show up for the group dialogues about 15% of the time. Without their presence, children do not fully appreciate the impact of their crimes, she said.

"Restorative justice is about building trust, but too often it feels poorly explained and misunderstood," Mattison said. "Victims are what make the process authentic — and their nonparticipation is a major source of concern."

Most Sunday mornings, Hubbard lights candles for the girls at a church near her home and prays that her attackers "find peace" in their lives. "All I want is to meet these girls, to look them in the eyes and see that they understand the pain they have caused," Hubbard said from her living room. "I'm not interested in seeing them punished. It's enough to hear them say, 'I'm sorry.'"

Justice by geography

Sarah Amand wonders why it took so long for her teenage daughter, Scarlet, to be offered the chance of a diversion program.

In ninth grade, Scarlet was charged with assault after she got into a fight at school. For the next year, she was summoned to hearing after hearing before a judge finally placed her on supervised probation. A probation officer would call every month, but otherwise left her alone. When Scarlet ran away for weeks at a time, Amand begged the probation officers to intervene and have her brought home — but they repeatedly refused, she said.

"It was terrifying not knowing where my daughter was," said Amand, a nurse from Brooklyn Park. "And it was all the more frustrating that the [juvenile] courts and probation didn't seem to care."

Then, months after the assault, an opportunity came that would reshape Scarlet's future.

Hennepin County offered to enroll her in an intensive restorative justice program known as the Power Program. Overnight, Scarlet gained access to a team of trained professionals, including a case manager who helped her find a job, return to school and begin to repair her fractured relationship with her mother. Twice-weekly group meetings and individual sessions with therapists taught her ways to cope with her impulsivity.

Scarlet was fortunate. Had she lived in the nearby counties of Anoka or Scott, she never would have been given the chance to participate in such an intensive support program. That's because those counties, like many across the state, exclude children from diversion if they have committed felony-level personal crimes.

Lack of money can also limit participation.

Even though Minnesota law requires that every county offer juvenile diversion, funding is left to individual counties. In many cases, county diversion programs are paid for through a mix of short-term grants.

Brown County in south-central Minnesota had to eliminate a promising teen court program after funding dried up. Officials in St. Louis County have dramatically scaled back its main restorative justice program after a $90,000 state grant ended in 2019. As a result, just one part-time staffer handles juvenile diversion cases for the state's sixth most populous county.

"It's had a huge impact on the amount of time and resources we can devote to these kids." said Laura Gapske, program director at Men as Peacemakers, a nonprofit that provides restorative justice programming for youth in St. Louis County.

In June, a joyful Scarlet — her long, red-dyed hair flowing from beneath her blue cap — arrived at her high school graduation ceremony in New Hope. Diploma in hand, she darted through a tunnel of screaming well-wishers until she found her mother. It was a moment that a tearful Amand once doubted she would ever see.

"To be honest, I probably would still be out on the streets, and nowhere near graduating, were it not for the love I got here," said Scarlet, speaking from the Power Program's meeting space in a north Minneapolis church. "The problem with the county and the courts — that whole world — is they focus on what you did, and not on the why, all the events that lead up to it."

Racial gap, revolving door

The boy arrived at the office beside his mother, then slumped in a chair with his hoodie pulled up and eyes cast down. He did not want to be there and had no intention of participating.

But he had no choice. Last fall, a Hennepin County judge ordered Jerome, a lanky 15-year-old from St. Louis Park, to complete the mentorship program as part of his probation after bringing a knife to school to confront a bully. No one was seriously injured, but the fight saddled him with a criminal record.

Trahern Pollard, 49, founder of the violence prevention group We Push for Peace, leaned forward from across the table, demanding attention. "Maybe you wanna be a doctor or a lawyer — you can't accomplish any of that shit with this," he said, waving a manila folder containing charges related to the assault.

Over the next hour, Pollard and his team of formerly incarcerated men urged Jerome to choose a different path, relying on personal anecdotes to convince him that felonies can plague young Black men for a lifetime.

And they would know.

During a tumultuous childhood on the South Side of Chicago, Pollard learned what it felt like to be on both ends of a bullet. Not long after surviving a gunshot wound, Pollard pulled the trigger on a rival gang member — a decision that ultimately earned him 13 years in prison.

That experience gives Pollard credibility with the troubled youth he now serves. Last year, his organization signed a $400,000 contract to provide mentorship and work readiness training for about 60 young adults as a form of post-charge diversion.

The goal: jam a crutch in the revolving door that disproportionately affects youth of color.

In both Hennepin and Ramsey counties, Black youth make up a larger share of kids charged, but they are significantly less likely to be offered diversion than white offenders, county data shows. Nationally, white youth are 30% more likely than Black children to have their delinquency cases diverted away from formal court processing, according to data from the National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Pollard acknowledges that the cards are stacked against the teens, who are often overwhelmed by troubles like poverty, trauma and community gun violence. But in his office, he forces everyone to confront the magnitude of their own actions and accept fault.

During weekly sessions, Pollard and his team teach kids how to create a résumé, conduct mock job interviews and navigate the terms of their probation. For some clients, that means dropping them off at school to avoid an altercation with other kids they might be fighting with — then returning promptly after the bell. Other times, it requires homing in on a child's interests to redirect energy into a more constructive outlet. One mentor, a licensed barber, even keeps clippers in his office to dole out free haircuts upon request.

With their assistance, Jerome found a job stocking produce at the neighborhood grocery store and developed more confidence, no longer needing to be prompted to make eye contact. At home, he began speaking to his mother in a new, respectful tone. She was delighted.

"Those men weren't cutting J no slack," said Antoinette Jones. "He's humbling himself through this."

Four months after he first walked through the door of We Push for Peace, the men held a graduation ceremony for teens who completed the program. Jerome beamed as he clutched the certificate, promising to keep coming around the center each week even though he no longer has to.

His mom vowed to drive him.

'A token of grace'

Wearing shiny gold shoes, Arriell seemed to fly as she ran the curve of the 200-meter race at Orono High School. Despite a strained hamstring, Arriell gained on her rivals in the backstretch, finishing near the front of a crowded race. Then she rushed to embrace her mother and two younger sisters who were screaming from the sidelines.

"You dig deep, girl!" shouted her mother, Lashawnda Demry, a nurse.

A year earlier, Arriell had emerged from the wreckage of the stolen car with a bruised lip and a sore back — but amazed that she and Debra were still alive. Her biggest fear was that her mother might find out, so she made no mention of the incident or her arrest after she returned home that evening from the juvenile detention center.

Like many adolescents, Arriell struggled socially and academically during the first year of the pandemic. She leaned on her younger cousin for emotional support. Despite living on the opposite side of Minneapolis, Debra would sometimes rush over to comfort Arriell.

"We were the only support system we had for each other," Arriell said.

To alleviate their sense of helplessness and boredom, she and Debra began hanging out with peers who skipped school and went on joy rides in stolen cars, Arriell said.

"People tell you about all the good things that will come to you if you do this or that, and you start to actually believe them," Arriell said, reflecting on the time. "Right from wrong becomes less important than the thrill that awaits you."

Two weeks after the crash, Arriell's mother received a letter from the Hennepin County Attorney's Office, disclosing that her daughter had been arrested. Her initial shock and anger was followed by relief. The letter said that Arriell, a first-time offender, qualified for a restorative justice program that would enable her to avoid criminal charges.

"That letter felt like a token of grace," Demry said. "I didn't really know much about restorative justice, but it sounded a lot better than a criminal record."

Over the next three months, Arriell was repeatedly encouraged through group dialogues to reflect on the underlying causes of her behavior. She began to think about her small circle of friends, and how they were taking advantage of her weaknesses — including her "hunger to feel like she belonged," she said. For the first time, she began to think about her own aspirations — including the possibility of attending college.

"They made me feel like a human being, and not a criminal," she said.

Yet Arriell has been left wondering what might have been. There are times, often late at night, when Arriell will send a text message to her favorite cousin, the one who always lifted her spirit with a joke or a compliment. Only after sending it does she remember that Debra is gone.

"I feel lucky that I got a second chance," said Arriell. "But why didn't my friend get that chance?"

About this series

Juvenile Injustice is a Star Tribune special report examining how Minnesota's juvenile justice system is failing young people, families and victims of violence.

Part 1: Broken promises, shattered lives

The consequences can be

deadly when the juvenile

system fails to intervene in the lives of Minnesota's most troubled kids.

Part 2: Justice 'by ZIP code, not fairness'

Minnesota has no

uniform standards for who can

join diversion programs or what they offer.

Part 3: Nowhere to go for most troubled youth

As youth detention

centers close, Minnesota runs out of places to

rehabilitate kids who commit serious crimes.

Part 4: 'Back door to prison' steals precious time

Minor offenses often funnel Minnesota youth from extended probation into adult lockup.

Part 5: Laying down the law for youths

Minnesota's juvenile justice system is broken. Colorado shows how it could be better.

How we reported these stories

Star Tribune journalists spent more than a year examining hundreds of juvenile court cases dating back to 2018 that involved violent crimes, including shootings, aggravated robberies and homicides. Many of the young people charged in those incidents had committed previous offenses, leading us to ask whether Minnesota's juvenile justice system was fulfilling its core promise of rehabilitating youth while protecting public safety.

Our review of court records was limited in scope because most juvenile case records are confidential. In Minnesota, juvenile crime records are only accessible to the public if the offense is a felony and the youth was at least 16. In cases where a court document was not accessible, we relied on interviews and documents obtained from relatives, victims and public-records requests from local law enforcement agencies.

Gathering statewide data about the effectiveness of rehabilitation efforts is difficult because the youth justice system in Minnesota is highly fragmented. The programs and the process of redirecting youth from formal judicial processing (known as "diversion") vary widely between counties. To better understand how these programs work, we created a survey that was sent to all 87 counties. We received responses from programs in more than half of those counties, representing 85% of the state's juvenile population.

Many young people do not re-offend. The juvenile courts shield their identities because a public record of their crime could be a barrier to attending college, obtaining a job or renting an apartment. Through the course of this series, we identify minors only by a first name — and only when parents have specifically consented. Those publicly identified after their deaths are the lone exception to this rule.

Series credits

Reporting: Liz Sawyer, Chris Serres, MaryJo Webster and Maya Miller

Photography and video: Jerry Holt, Mark Vancleave, Cheryl Diaz Meyer, Christine Nguyen and Deb Pastner

Design and development: Bryan Brussee, Josh Penrod, Jamie Hutt, Josh Jones and Dave Braunger

Graphics: C.J. Sinner, Eddie Thomas, MaryJo Webster and Josh Jones

Editing: Eric Wieffering and Abby Simons

Copy editing: Catherine Preus and Amy Kuebelbeck

Audience engagement: Anna Ta, Nancy Yang, Ash Miller and Tom Horgen

Share your story

The Star Tribune is continuing to report on Minnesota's juvenile justice system. We would like to hear from judges, prosecutors, young people who have been involved in the juvenile justice system and their parents, and victims of crimes. Our reporters will not share your information without your explicit permission. You can reach Liz Sawyer at 612-673-4648 or at liz.sawyer@startribune.com, or via the encrypted messaging app Signal at 612-916-1443. Chris Serres is at 612-673-4308 or chris.serres@startribune.com, or on Signal at 612-910-7134.