Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

We take the electricity grid for granted. Flip a light switch, the juice will flow.

But behind the scenes, a complex balancing act ensures that electricity travels safely from power plants to millions of homes and businesses in the Twin Cities. And it's only growing more complicated as more wind and solar power join the grid.

Electricity mechanics were on the mind of David Piper when he posed a query to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by reader questions.

"I am curious about how electricity is delivered to our homes in the metropolitan area. Where is it produced and how is it distributed?" he asked.

The power plants

Most of the metro area's electricity is supplied by Minneapolis-based Xcel Energy, the state's largest utility with 1.3 million customers.

The warhorses of Xcel's electricity generation fleet are two nuclear plants in Red Wing and Monticello, three big coal-fired plants in Becker, and a fourth coal plant in Bayport. Xcel plans on retiring all of its coal plants by 2030.

The company also has six major natural gas-fired power plants, three of which are in the Twin Cities, and several gas "peaker" plants that operate only when demand is high.

Wind makes up 21% of Xcel's power generation in the Upper Midwest and is drawn from rural power plants, particularly in southwest Minnesota. Solar farms provide 3% of Xcel's electricity. Nuclear generates 30%; the rest comes mostly from fossil fuels.

If you live close to a power plant, you are more likely to receive electricity from that plant. However, the source of your electricity also depends on the time of day.

"It is likely that at certain times the electricity in homes will come from faraway places," said Michael Lamb, Xcel's senior vice president for transmission.

For instance, wind power production is strongest — and cheapest — in the early morning hours, so it will be dispatched first by the regional power grid operator.

The power 'freeway'

Whether it is generated at a wind farm or a coal plant, electricity is loaded onto a network of high voltage transmission lines. "You can think of it very much like a freeway system," Lamb said.

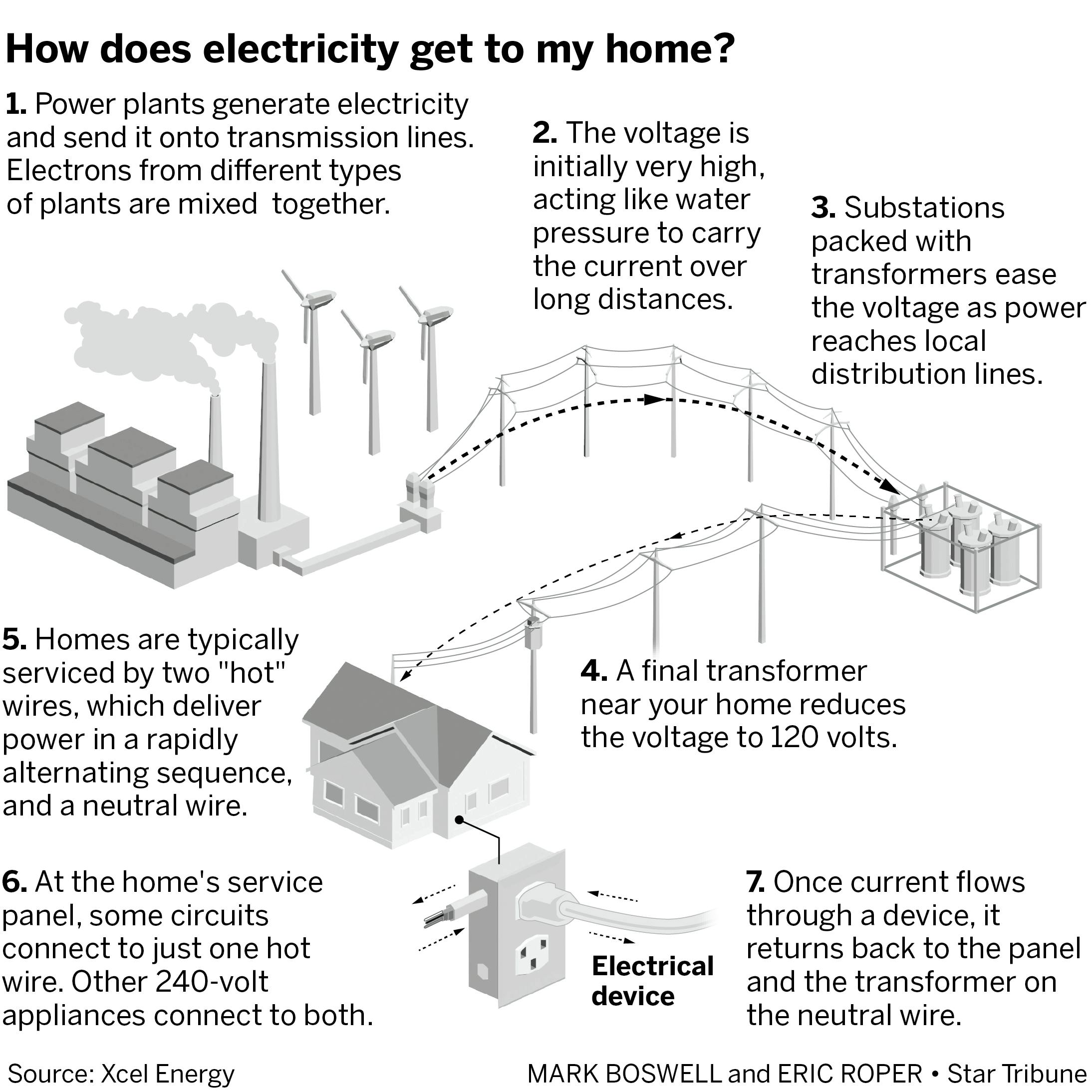

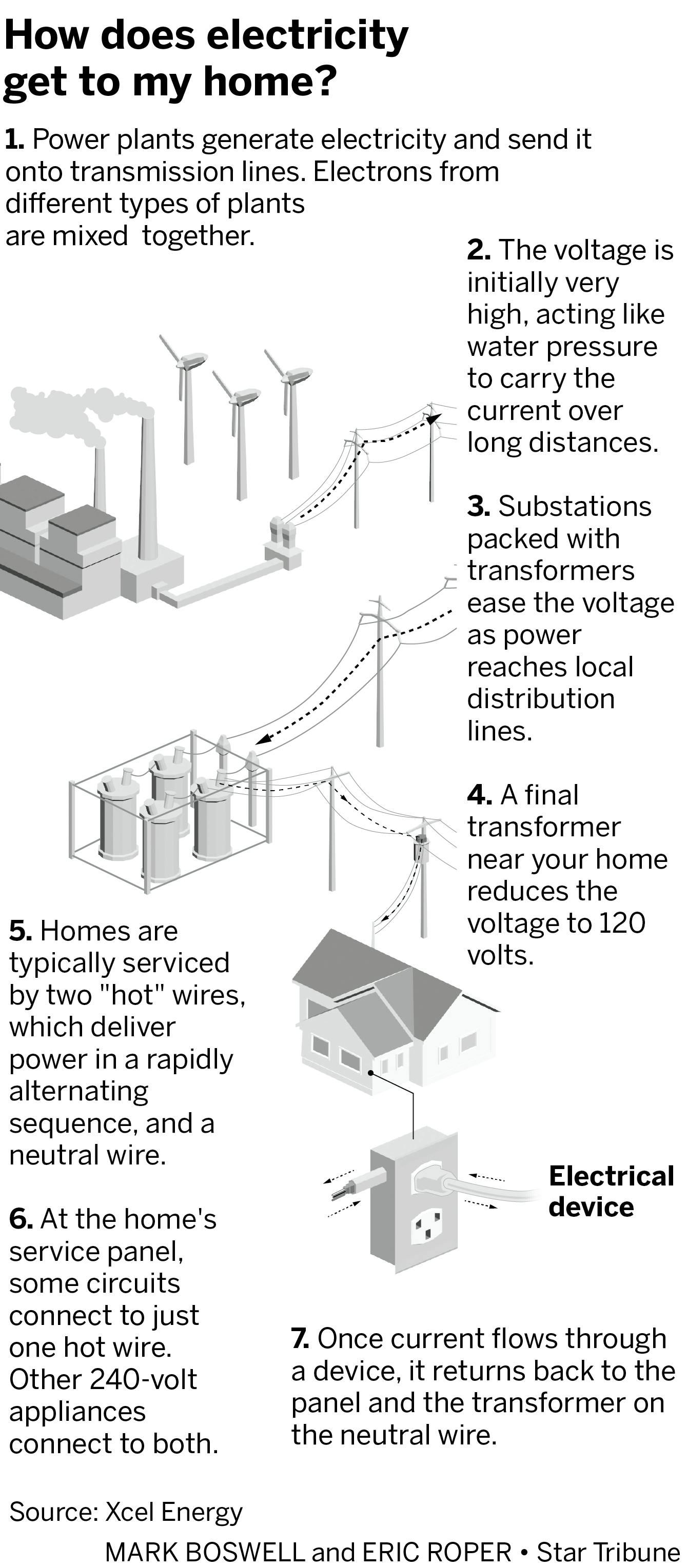

The transmission and distribution system doesn't differentiate between power sources; electrons from coal or wind plants are all mixed.

"Once an electron is on the grid, it flows based on physics to its ultimate destination," Lamb said.

Voltage pushes electric current through power lines, acting like "water pressure," Lamb said. That pressure is huge as it leaves the plants — reaching hundreds of thousands of volts. But substations packed with transformers ease the voltage as the power reaches local distribution lines.

A final transformer near your home, sometimes located in an alley, cuts the pressure down to 120 volts. From there, power typically enters the home on two "hot" wires accompanied by one neutral wire. These pass through the electrical meter to the household panel.

The two 120-volt hot wires operate on opposite phases, meaning they rapidly alternate supplying current. Most household circuits connect to just one of the hot wires, but 240-volt appliances like electric stoves connect to both. These can be found by identifying wider "double-pole" circuit breakers in the panel.

But once current flows through a light fixture or appliance, it doesn't disappear. Rather, it returns back to the panel via the neutral wire in household wiring. From there, it links up to the main neutral wire and heads back to the transformer.

The grid

The electricity we enjoy in Minnesota travels on transmission wires that are linked with similar wires in 14 other states and the Canadian province of Manitoba. This regional "grid" is overseen by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), a nonprofit organization based in Indiana.

MISO's primary role is to balance electricity supply and demand in the region. At MISO's operations center in Eagan, workers monitor real-time power flows on maps splashed across giant screens.

Generating too much or too little power on the grid could damage wiring and other equipment. During emergencies — when power supply is constrained — grid operators like MISO may order rolling blackouts to maintain that balance.

Wind and solar power bring new challenges to power grid management. While they are emissions-free and can be accurately forecast, wind and solar can't be dispatched at will — making them less reliable than traditional power plants.

Grid failure in Texas

The failure of Texas's electricity system earlier this year illustrates what happens when the grid's delicate balance goes haywire. It occurred when winter Storm Uri slammed the central U.S. this February, particularly the south.

Most of Texas is covered by its own grid operator, known by the acronym ERCOT. Natural gas is the biggest fuel for Texas' electrical system. When temperatures plunged, gas equipment froze up, reducing electricity supply just as demand soared.

Texas' grid has less spare generation capacity than MISO and other regional grids. Also, unlike MISO, the Texas grid doesn't have strong ties to other regional grids, making it difficult to import power during an emergency.

A University of Houston study found that 69% of Texans served by ERCOT lost power; the average outage was 42 hours. And it could have been worse.

The state's grid was actually minutes away from total collapse during the storm because its frequency — the number of times per second the current alternates — dipped below the U.S. standard of 60 hertz.

Staff writer Eric Roper contributed to this report.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Is Minnesota's power grid ready for widespread electric cars?

Why does Minneapolis keep planting trees under power lines?

How do cities make Mississippi River water safe to drink?

When you flush a toilet in the Twin Cities, where does everything go?