Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

The Twin Cities is one of the mighty metro areas of the United States. But its largest city is smaller than the impressive skyline might suggest.

About 430,000 people live in Minneapolis. Compared with central cities in the nation's top metro areas, Minneapolis represents one of the smallest slices of its regional pie.

Reader Steve Brandt wondered why Minneapolis is so much smaller than cities it considers peers, like Seattle, Denver and Portland. Brandt sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

"If you look at our square mileage, we are a very small geographic city. And that limits our population. So why was that?" asked Brandt, who retired from the Star Tribune in 2016 after 40 years as a reporter. He is now an elected member of the city's Board of Estimate and Taxation — as well as a friend and neighbor of mine.

A portion of the answer involves Minneapolis' sibling to the east, St. Paul, since Minneapolis and St. Paul combined would have roughly the population of Seattle. My colleague Kevin Duchschere will answer a separate reader question about why the cities never merged in an upcoming column.

But why didn't Minneapolis gobble up its surrounding suburbs? The history reveals that it nearly did. Numerous efforts failed, resulting by the 1950s in a fragmented metro area desperately seeking regional government services.

An 'inelastic' city

Minneapolis' population is a mere 15% of the urban metro area that surrounds it, according to a Star Tribune analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. That makes it the eighth-smallest central city as a share of its urbanized region among the country's top 50 metro areas.

The analysis focused only on the nonrural parts of the country's metro areas, which accounts for about 3 million people in the Twin Cities.

On the other end of the ranking are sprawling, lower-density cities like Jacksonville, Fla., San Antonio and Oklahoma City — which account for most of their metros. Excluding water, Jacksonville covers an area more than 13 times wider than Minneapolis.

These are what David Rusk refers to as "elastic cities" in his book "Cities Without Suburbs," referring to cities that grew outward with their regions. Rusk, who is the former mayor of Albuquerque, argues that elastic cities have many advantages over their "inelastic" counterparts that remained smaller — like Minneapolis.

Generally "inelastic" cities developed earlier, surpassing 100,000 residents before 1890, Rusk wrote. That was the case in Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., St. Louis and several other smaller central cities.

Rusk said one reason Minneapolis became constrained is that the U.S. government originally subdivided the Minnesota area (and other nearby territory) into a grid of townships. These were the foundation for incorporated villages that later surrounded the city.

This is distinct from cities in the South and West, he said, which are largely surrounded by unincorporated communities.

"Annexation is still very significant in the South and the West, which does not have this 'little boxes' structure of the Northeast and the mid-Atlantic states and the old northwest territories," Rusk said, referring to metro areas packed with smaller cities.

Minneapolis expands

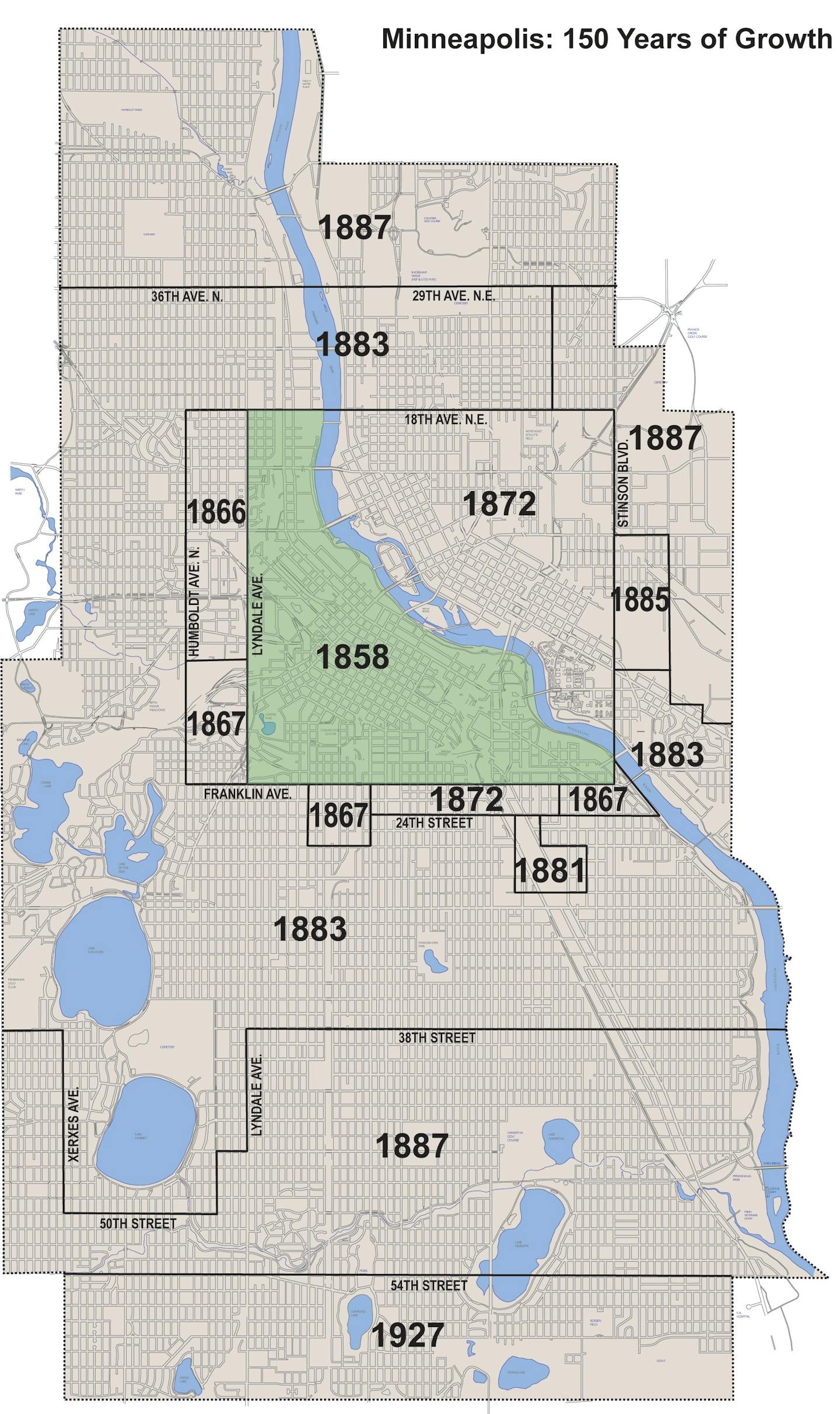

Minneapolis has actually grown significantly since its infancy in the 1860s, when the boundaries generally followed the present-day downtown area. As the population soared in the 1880s, the city added about 40 square miles of land in 1883 and 1887 annexations — quadrupling its size.

"That was pretty much open land, so there was lots and lots of opportunity to accommodate the big population boom that happened between … 1880 and 1900," said Minneapolis historian Iric Nathanson.

By the early 1900s, the rural residents of townships outside Minneapolis were growing worried that Minneapolis would take their unincorporated land.

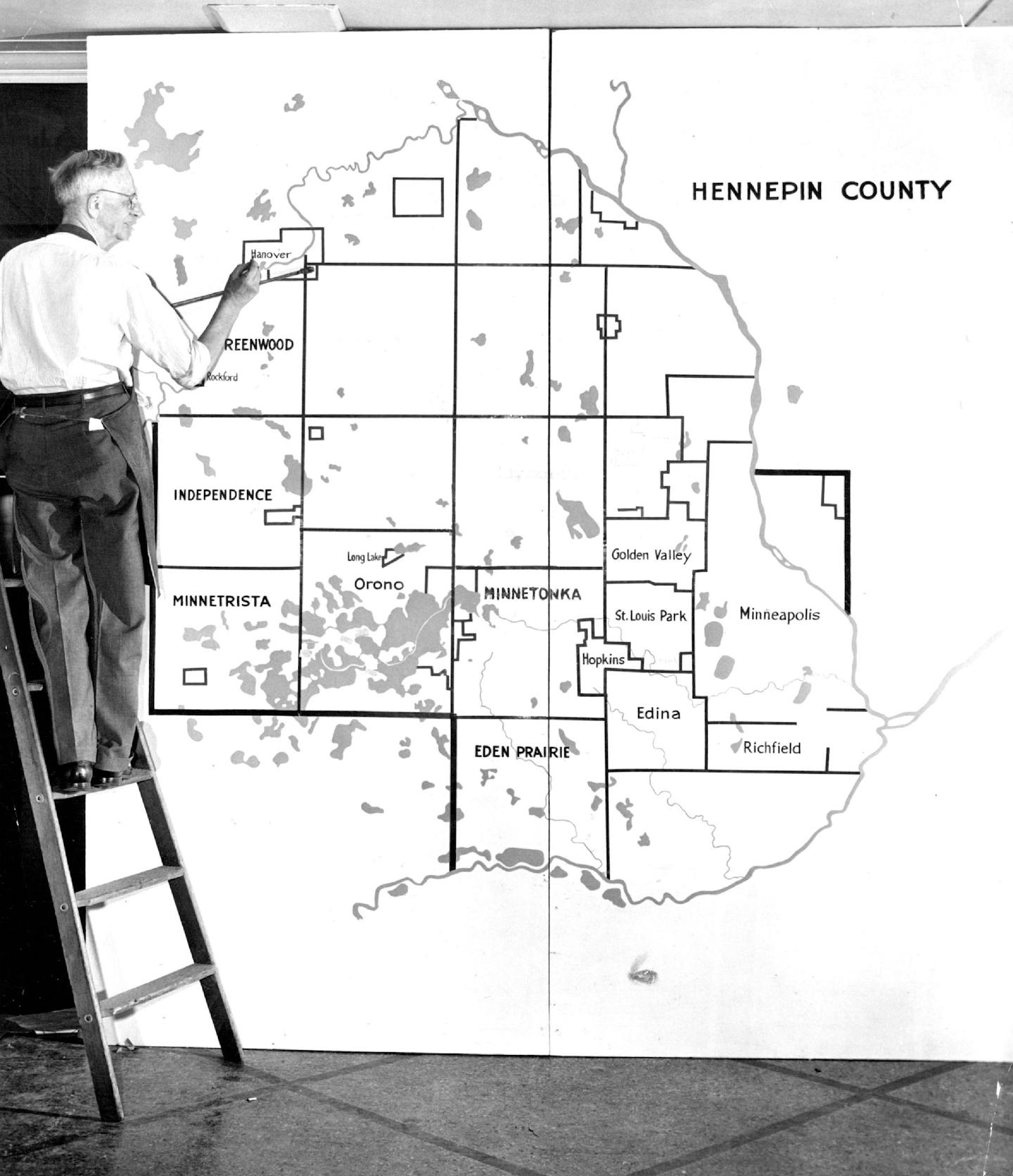

"Villages have been incorporated in Hennepin County thick and fast because the county residents feared that they might be annexed by Minneapolis and be compelled to pay increased taxation," the Minneapolis Tribune reported in 1912.

An attorney for Hennepin County said at the time that a stranger wouldn't be able to locate the "village" in the villages of Richfield, Golden Valley, Edina and Brooklyn Center — which were largely farmland.

Robbinsdale and Columbia Heights, by contrast, were considered more traditional villages. Both were soon seeking to be annexed by Minneapolis, since joining with the city generally meant better schools, utilities, infrastructure and public safety services.

Suburbs seek services

In 1923, legislators from Minneapolis and Robbinsdale authored a bill creating a process for Minneapolis to annex an adjoining village. On the House floor, Robbinsdale co-author Thomas Girling amended the bill to require approval from a five-eighths majority of the people being annexed — rather than a simple majority.

"We, in Robbinsdale, want to become a part of the city of Minneapolis," Robbinsdale Mayor Henry Uglem told the Minneapolis City Council in September 1923. The Minneapolis Star reported that the move had been "talked of for a generation." It seemed like such a sure thing that Parks Superintendent Theodore Wirth began planning to acquire Crystal Lake and nearby land.

But the annexation repeatedly failed to win a five-eighths majority over at least seven referendums in Robbinsdale — despite coming close. In 1931, for example, the vote was 913 in favor and 760 opposed. By 1933, Robbinsdale's annexation supporters were asking the Legislature to change the law to require only a simple majority.

On the other side of Minneapolis, Richfield residents secured enough votes in 1926 to allow annexation of a portion of the village by its northerly neighbor. This 5.4-square-mile addition expanded the city's southern border from 54th Street to 62nd Street.

"[Richfield] is expected to be the first of a number of suburban annexations that will help to push Minneapolis further to the front among American metropolises," the Star reported in 1927.

That would be the city's last significant annexation.

The City Council of Columbia Heights — which became a city in 1921 — told Minneapolis in 1928 that it wished to be annexed. "It is up to us to show [Minneapolis] that we are desirable of acceptance," said Mayor William Foster, who at 22 years old was dubbed "boy mayor" by the Minneapolis Journal.

Minneapolis officials did not want the city located in two counties, however, and Anoka County declined to give up Columbia Heights. That, combined with the debt burden Minneapolis would inherit from its neighbor, ultimately soured the deal.

A fragmented region

Calls for annexations were revived in the 1950s as the burgeoning suburbs strained to keep up with postwar growth. Proposals were floated to fold Brooklyn Center and the remainder of Richfield into Minneapolis.

But some Minneapolis leaders still considered the 1920s Richfield annexation a "poor deal," according to a 1952 Star editorial. It proved costly to add improvements to the area and then the Great Depression decimated property values, the Star reported in 1954.

"Annexation used to be widely discussed in adjoining communities," the Star editorialized in 1954. "After [Richfield] Minneapolis acquired such a big debt in relief bonds that no suburb wanted to be part of the city. Now the situation has changed and Minneapolis is in pretty good financial condition."

By 1959, a state commission studying annexation issues lamented what had become of the Twin Cities metro area. New cities created in the 1950s had only made things worse.

"The 104 municipalities which have arisen in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, making up a part of the largest number of governmental subdivisions in any American metropolis, have created problems in furnishing adequate, economical, municipal services to those living within the myriad of separate municipal governments all within the metropolitan area," the commission wrote.

These discussions would ultimately result in the creation of the Metropolitan Council in 1967 to provide services to the entire region.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why is Uptown south of downtown in Minneapolis?

Why were so many of Minneapolis' Park Avenue mansions torn down?

Why does everyone love to hate Edina?

St. Paul vs. Minneapolis: Why can't the Twin Cities get along?

Why do tiny cities like Lauderdale, Landfall, Lilydale, & Falcon Heights exist?

From bankrupt racetrack to aviation hub — what remains from MSP Airport's early days?