I thought Sid Hartman died once in the passenger seat of my car.

We were snaking down a jam-packed 7th Street after finishing one of his columns in early 2016. It was a midwinter evening with slush on the street and packed snow in the gutters.

"I can't believe these guys on these bicycles," said Sid, 95 then, as he glanced out his slowly fogging window. "They're crazy." We turned left at First Avenue.

"Sid, what do you want to do for a column on Sunday?" I asked at the stoplight.

There was no response.

"Sid?" I said louder, glancing right.

He was still, his eyes glazed and focused on nothing.

"Sid?!" I yelled.

For the first time in my life I had a hot flash. The hair on my neck stood up. I tried to stay calm, but all I could think was, "I'm going to have to call an ambulance and give a quote to the newspaper."

Imagine calling to someone when they are upstairs — that is how loudly I yelled "Sid!" to a man sitting 24 inches away.

He turned with a confused look on his face and said, "Huh?"

The light turned green, I touched the gas and drove him home.

• • •

My relationship with Sid started because I typed faster than anyone he had ever met.

Paul Klauda, a Star Tribune editor, was a professor of mine at St. Thomas and in 2006 he told me that they had a spot available for a seasonal prep sports assistant.

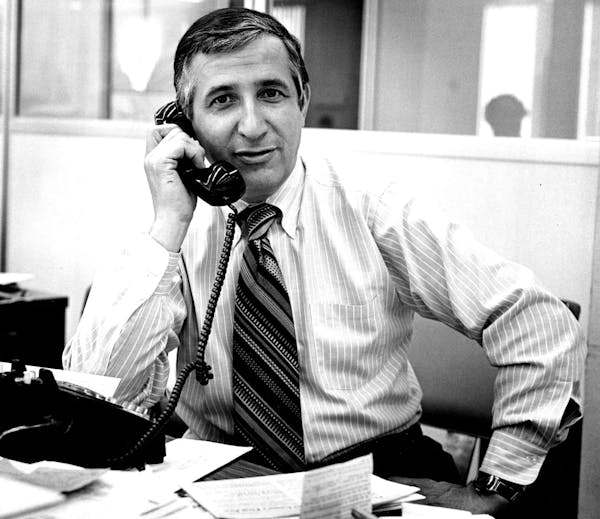

These were part-time, entry-level jobs answering phones, taking prep highlights and compiling boxscores and, for one seasonal employee, doing Sid Tapes. It was written on the calendar that way: "4-8, Sid Tapes."

I did Sid Tapes, which was simply transcribing Sid's interviews, and I did them very, very quickly. That ingratiated me to Sid in a way I never could have imagined.

After I proved that I could type, I was given other tasks. Carrying out a box of his "Sid Hartman's Great Minnesota Sports Moments" books to his Cadillac, for example.

This was at the old 425 Portland Ave. building where Sid had an office that looked like the smallest maze. Filing cabinets, manila folders, envelopes, notepads, decades worth of media guides, photographs, batteries, tape recorders and mountains of blank tapes.

He called me in one day and asked me if I would mind carrying one of these boxes. It must have weighed 40 pounds.

I lugged it into the elevator outside his office, and when I dropped it on the floor, the elevator shook. When I hit the ground floor, I hoisted it up on my chest and squeezed into the revolving door and maneuvered down the 4th Street sidewalk to the loading dock where Sid's car was parked sideways across three spaces. I heaved it into the back seat and took a serious moment to catch my breath.

As I made my way back toward the office door, Sid came flying out, carrying two boxes.

• • •

Another time I thought Sid was dead was when I got a phone call saying he had fallen and broken his hip.

I was unaware how dire a situation that was for an elderly person — and Sid was 96 at the time — but based on the tone of the conversations, I began to think Sid would never work again. I got hold of his son, Chad, to see if I could come visit.

Sid was in a recovery room at Fairview Southdale, lying in a hospital gown with an array of machines connected to him and doctors and nurses and family coming in and out of the room. I had never seen him in a vulnerable position. I went to his bedside and asked him, as quietly and kindly as I could, how he was doing.

He rose up slightly, "You tell them not to touch my column."

He was back to work three weeks later, writing about the Gophers hiring P.J. Fleck as the football coach.

He would publish 612 more columns.

• • •

When you work with someone as they age from 86 to 100, their mortality is always on your mind. But I can say with clarity that I might not be alive if I hadn't met Sid.

After working at the paper for two years, I was laid off during downsizing when the Star Tribune was going through bankruptcy in 2009. Sid raised hell. He could not believe he was not getting his way. But I wasn't full-time or a guild member, so I was gone.

I went to work at a temp agency and was hired for office positions and I couldn't get comfortable. The people I worked with were kind and generous, and they reached out to me and gave me lifelines. And I rejected them.

I used to chain smoke in the parking garage and think, "I'm going to kill myself." Whatever the thing is that makes people happy and gives them purpose had left me.

Sid called me a year after I was laid off and said, "I'd like to take you out to Murray's."

We had dinner and he told me that the paper had an opening and he wondered if I would take it. He wasn't asking a question. When I went back to work I was employed by the Star Tribune, but I was there for Sid, and it was intensive. Whatever other work I had to do for the paper did not matter to him.

We went through hours and hours and hours of interviews. It was maddening at times. On Sundays he would show up at 4 p.m. with the tapes from his WCCO radio show and I would transcribe for upward of six hours using a foot pedal rewind mechanism and an old cassette player.

He would come in on Monday and complain that I had missed someone. He would ask me if I had gotten to that interview with Tubby Smith from three weeks ago, knowing full well that we had done two Tubby interviews since then. He would tell me there was something in that tape from three weeks ago that he might need.

Sometimes it was a standoff over the principle of the thing: I would refuse to do it, and he would refuse to stop asking.

• • •

I kept searching for refuge outside of the office. I became an alcoholic. I got arrested. I lost relationships. I lost my entire sense of self.

But I kept going to work. Every day. I never missed a day of work with Sid.

I remember once leaning over him at his computer — I can see his face right next to me — and him saying, "Have you been drinking?"

I denied it. He said I was lying. He was right and he never said anything about it again.

When he saw my mother he would tell her, "He's like a son to me."

When he saw my father he would tell him, "I couldn't do this without him."

My wife sat next to him in the Twins press box and all of a sudden, he was the most charming man on earth.

He came to my wedding dressed better than I was.

And he told me, constantly, that he hoped I wouldn't leave him for another job.

And because Sid kept going to work, I kept going to work. It was the most stable thing in my life. But somewhere in all of those columns, in all of those years, in all of those tapes, I found a thread and started the work of trying to find myself outside of the office.

I never told Sid about any of it.

I didn't tell him about getting sober or going to years of therapy or regaining some faith in myself.

I just kept going to work.

• • •

Eventually Sid started writing at my desk more than at his because, to be fair, his desk was a mess.

He was frailer than before and getting up and down was difficult, so we would shimmy from desk to desk in our chairs without standing up, like bumper cars.

He still would complain that I didn't do enough tapes — we kept a list of his interviews that is right next to my computer at the Star Tribune. Sometimes, and I'm sure he knew, I crossed out tapes I hadn't done because I knew he wouldn't use them.

I can finally say I was correct about that.

Over the past three years, Sid softened. His nurses, God bless their souls, saved his life every day, and he knew it.

And when Sid got softer, we all kind of did.

Most nights I would help him put his jacket on before he left.

"Help me with this, will ya?" he would say. He'd stand up, a little unsteady, and I'd slide it over his shoulders, which were more angular than they used to be, and I would take just a moment to pat him on his back.

But Sid's intensity and desire to be the best never waned.

Two months before he turned 98, he covered the Super Bowl in Minneapolis and wrote six columns in seven days, getting interviews with NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and a slew of Hall of Famers.

Sid never thought he was doing enough, even that week. I remember kneeling down in front of him after he finished covering the game, forcing him to stare me right in the eyes, and telling him how unbelievably proud he should be.

"OK, OK," he said.

• • •

When Sid died, I was sitting on my couch, logged into his column, typing notes to send to him about the Vikings game.

When Sid died, I was already thinking about him. I was thinking about ideas that would make him happy and argue for his point of view — which was always that better days were ahead and, if the home team had lost, that today really wasn't so bad.

When Sid died, I was still hoping to see him again soon.

When Sid died, I was still holding onto the notion that somehow, someway, this world could get back to normal.

That notion, for me, is gone now. It is a small, selfish thought, but my life will never be the same.

People have thanked me the past few days for helping prolong Sid's life by helping prolong his career. As if I did him some favor.

So I'll take this time to clarify things and say something I didn't say to him: Sid Hartman saved my life.

He asked me to do a very simple thing: Go to work with him, every day.

It was a great honor.