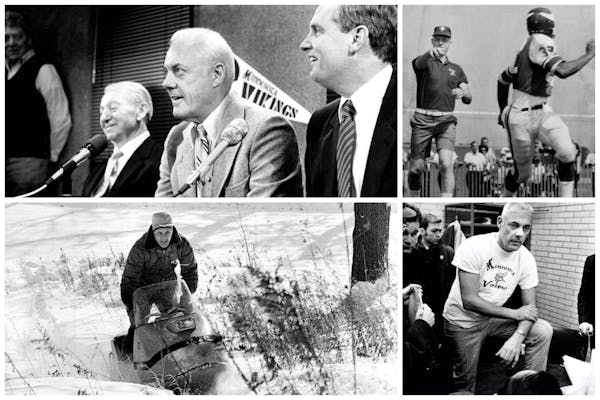

Bud Grant, the most iconic sports figure in Minnesota history, died Saturday.

He was 95.

Grant was a standout athlete for the Gophers, played professional basketball for the Minneapolis Lakers and starred in the NFL, but made his mark in the state as coach of the Minnesota Vikings, leading them to four Super Bowls in his 18 seasons and earning a spot in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

More than that, the avid outdoorsman was known for his statue-like appearance on the sideline as his teams played in the winter elements. There was a weekly study in stoicism that fans of the Vikings saw, month after month, year after year, from Grant. The no-heaters-on-the-sidelines, no-gloves-allowed, weather-be-damned toughness he displayed — and demanded from his players. The chiseled, taut, expressionless face with the clear blue eyes that we saw on the sidelines.

Somewhere along the line, Harry Peter Grant Jr., born and raised in Superior, Wis., came to embody how a lot of Minnesotans liked to think of themselves: hard-working and successful; steady and reliable; unflappable and independent.

"He never embarrassed a player, never criticized or chewed a player out in front of anybody else," former Vikings running back Dave Osborn said. "If he had something he didn't like about you, he'd take you aside and talk to you.

"Bud just had a knack for leading, handling people. He was a great football coach, but Bud could have coached a sport he didn't know anything about because he just knew how to handle people."

Grant's wife, Pat, died in 2009. They had six children — Kathy, Laurie, Peter, Mike, Bruce and Dan. Bruce died in 2018 from cancer. Bud Grant is also survived by his companion, Pat Smith.

Vikings coach Kevin O'Connell, in a statement issued by the team, said, "Bud was gracious with his time, meeting in his office weekly to discuss football and life. I will forever cherish those conversations because they made me a better coach, a better husband and father and a better person."

The team's principal owners, Zygi and Mark Wilf, said, "No single individual more defined the Minnesota Vikings than Bud Grant. A once-in-a-lifetime man, Bud will forever be synonymous with success, toughness, the North and the Vikings."

Athletic excellence

A few years ago, sitting in his office at the Vikings headquarters, Grant took some time to talk about his life, his career, his status in Minnesota. To those who watched him coach the Vikings, that image is frozen in time: The simple jacket, the baseball-style cap, the emotionless face, the breath frozen in the air at old Met Stadium.

The man who took pride in always being able to do things his way did it that way for a reason.

"Well, I tried to," Grant said. "Having been from here, having traveled the state playing baseball and basketball, I got to know what the fabric of this part of the world was. ... This sounds corny, but I was proud that I was from this part of the world, which is not very well represented in the rest of the country. I'm still patriotic. I don't wear it on my shirt or anything. But I'm patriotic. Not just for the country, but for the region, for the state, for my team. I know I represented the state, and I tried to do it well."

Just about everything Grant tried, he did well. A three-sport high school star at Superior Central, Grant starred in football, baseball and basketball at the University of Minnesota.

Every step of the way, he did it his way:

* A first-round draft choice of the Philadelphia Eagles in 1950, he rejected what he thought was a sub-par offer and spent a year playing for the NBA's Minneapolis Lakers and operating as a pitcher for hire in town ball games all across the state.

* After two outstanding seasons with the Eagles, he once again snubbed a sub-par offer, became the first man to play out his NFL option, then moved to Winnipeg of the Canadian Football League.

* Installed as head coach there by age 29, Grant coached the Blue Bombers to four CFL championships in 10 seasons.

* Finally persuaded to return to Minnesota, Grant coached the Vikings for 18 seasons. He won 158 games, 11 division titles, took the Vikings to four Super Bowls, eventually retiring to spend more time with another of his life's loves, the outdoors.

He was never cut, never fired.

As the years passed, he became a beloved figure in the state.

He had yearly garage sales at his house to sell old memorabilia and personal items, greeting buyers warmly, although he was unyielding on prices.

He maintained his Vikings office, first at Winter Park and then at the new TCO Performance Center in Eagan, where the team's coaches stopped by for advice.

He attended team functions, told stories of his amazing life adventures to media members, and stayed active until the final days of his life.

And he cemented his legend status with the fan base when he walked to midfield during a Vikings outdoor playoff game at TCF Bank Stadium in 2016 at age 88 wearing short sleeves. The temperature was 6 below.

Northern beginnings

Grant grew up in Superior, the first of three sons of a fireman. He was born in 1927, just before the Depression and grew up on First Street, always feeling the wind coming off Lake Superior. Money was always tight.

"I was raised during the Depression, I lived during the war," Grant said. "For a young person, it was a traumatic time. There was rationing, we didn't have cars, or tires or gas or clothes. There is a mindset that you have to make a living, you have to survive. You have to rise above where you're at."

Sports became his way of doing it.

That is, after a bout with polio. Grant contracted it at age 8, and it made his left calf and thigh smaller than his right. But on the advice of the doctor, Grant was encouraged to take part in sports as therapy.

In the years to come Grant, though skinny, grew strong and tall. But even as he was starring at Central High, he was preparing himself for the service. He graduated in 1945 and promptly enlisted in the Navy only to have the war end shortly thereafter.

Still, the months that followed would be crucial in Grant's development.

First, Grant crossed paths with legendary coach Paul Brown at the Great Lakes base north of Chicago. Brown was coaching the base football team, which was filled with great players, a team strong enough to beat Notre Dame in a game that year. Grant was impressed with the way Brown taught the game.

Shortly after that Grant was shipped to a base in San Francisco, where he quickly used a loophole to gain his early release from the Navy. Grant had decided he would attend Wisconsin before he enlisted in the Navy.

He was spending his day learning how to drive landing craft in San Francisco when he saw a notice saying that anybody enrolled in an accredited college who was still in the states could get an early discharge. Grant called up to Wisconsin and got coach Harry Stuhldreher — one of the famed "Four Horsemen of Notre Dame" — to send a letter confirming his enrollment.

By the time he made it back to Superior, Grant had changed his mind. His time in the service made Grant want to stay closer to home.

"It's 350 miles from Superior to Madison," Grant said. "Minneapolis is 150. I'd been away long enough. So I had to call Wisconsin and tell 'em I wasn't going there. It was a hard call to make."

Even that decision was one informed by Grant's past. Wisconsin had offered Grant $100 a month, a part-time job and the use of a car as long as he kept up his grades. Minnesota offered nothing. That appealed to Grant for a number of reasons, including the fact that it wouldn't make Grant beholden to the football team. With the Gophers, Grant played football in the fall, basketball in the winter, but skipped spring football in favor of baseball. Minnesota was also where Grant met a young sportswriter named Sid Hartman, the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

Twice Grant was named all-conference in football, where he played both ways. He was an MVP in both baseball and basketball.

While he excelled at both football and basketball at the professional level, baseball might have been his greatest love. Grant pitched in town ball games — once making $150 to pitch for a team in Rice Lake, Wis., on a Sunday after a Gophers game — while he was at the U, and for a couple of years afterward.

Even late in his life, Grant said nearly as many people came up and talked to him about his baseball days as his days with the Vikings.

"They'll say, 'I saw you down in Caledonia, pitching,' " Grant said. "Or, 'I remember that hit you got against Red Wing.' I don't know if I could have played baseball [professionally], as tedious as it is to be an outfielder. I could hit. That's what I could do best. But that's not where the money was, so I had to pitch."

The NFL calls

After Grant's final season of football at the University of Minnesota, Hartman convinced him to forgo his final year of college basketball and sign with the 1949-50 Lakers for $3,500. That plus his baseball earnings allowed him to turn down the Eagles' offer of $7,500 made to him after Philadelphia took Grant in the first round of the NFL draft the following spring.

Grant was a substitute for two seasons, which included one NBA championship. But by the time the 1951 NFL season came around he was ready to play football again.

As a rookie, playing defense, Grant led the Eagles in sacks. The following season, playing mainly offensive end, Grant caught 57 passes — second most in the league. In the wake of that season, Grant asked for $9,000 for 1953. The Eagles offered $8,000. Despite feeling pressure from the likes of NFL Commissioner Bert Bell — who invited him to his Philadelphia office and advised him to sign — Grant was having none of it.

He had played out his option and he left, going to Winnipeg, which had offered $10,000.

"It was more money," Grant said. "And the Canadian dollar was worth more than the American dollar then. It was cheaper to live in Winnipeg than in Philadelphia. I did all my sums, all of that. Travel, living expenses, the whole thing. I was doubling my salary going to Winnipeg."

An all-star in the CFL — Grant once intercepted five passes in one game — Grant was promoted to coach in time for the 1957 season.

In 10 seasons as the Blue Bombers' coach, Grant won four Grey Cups (1958, '59, '61, '62).

Pressed for his fondest memory from that time, Grant recalled the '58 championship.

"There was still some question," he said. "I was a player, then I was a coach. Could I do it? Could I go from playing to the coaches' ranks? The second year we won the Grey Cup, and Winnipeg hadn't won in years. ... There was the parade, the usual thing. But thing is the realization of what you had done, what you could do. There had always been the question, am I doing the right thing? At that point I remember thinking, 'Well, maybe this is my destiny. Maybe this is what I'm supposed to do.' I never aspired to be a coach; I fell into it. I realized this is maybe what I can do best."

Grant was also making friendships that would last for years; with Jim Finks, the former NFL quarterback who was running the CFL franchise in Calgary; with Jerry Burns, who Grant brought up in the summer during training camp to consult.

Vikings owner Max Winter tried to woo Grant back to Minnesota to become coach of the expansion Vikings, but Grant was unmoved.

"They weren't going to win for a few years, and I didn't think it was a good time," Grant said. "I had a good thing going [in Winnipeg]. I said, 'Call me the next time.'"

The second time came in time for the 1967 season, after the Vikings had fired Norm Van Brocklin. The story goes that Finks told the Vikings PR director, Bill McGrane to go pick up Grant at the airport.

"I don't know him," McGrane said.

"He'll be the only one who gets off the plane and looks like the town marshal," Finks replied.

The Vikings had registered one winning season when Grant arrived. He went 3-8-3 in his first season, but the Vikings were amassing the players who would make them great for years to come. Clinton Jones was drafted with a pick acquired in the trade of Fran Tarkenton to New York, part of a 1967 draft class that also included Gene Washington, Alan Page, Bob Grim and Bobby Bryant. Ron Yary was the No. 1 pick a year later, and Ed White came in 1969.

"The most important thing a coach does is evaluate people," Grant said. "That is something I could do as well as anybody. Not better than anybody, but as well as anybody. Simply because I'd played nearly every position, except interior lineman. ... I had an insight into what it takes to play those positions. I don't think we ever cut a player who played with another team effectively."

Unprecedented success

In 1968, the Vikings made the playoffs for the first time, going 8-6. A year later they won the NFL championship and advanced to the first of four Super Bowls. From 1968 through 1980 the Vikings won 11 divisional championships. From his first season through the 1983 season, Grant compiled a 151-89-5 regular season record.

Again, all done his way.

Grant was never one to let a game consume him. He was legendary for holding practice later in the day if he wanted to go duck hunting. Earlier, if he wanted to go hunt grouse. The coaching staff's day revolved around when Grant wanted to play racquetball.

"He had that cabin up in Gordon, Wisconsin, and there were times in the spring, he'd go up there," the late Vikings trainer Fred Zamberletti once said. "And Finks would try to get ahold of him, trying to do a trade, and they couldn't get him. One year, for his birthday, they wanted to give him a pager, but he wouldn't take it."

Grant was not a micromanager, but he made sure his coaches knew he knew what they were doing.

"This is how he put it," said Paul Wiggin, a long-time member of the Vikings organization who coached with Grant for one season. "He said, 'I don't drive around this building at night to see whose windows are lit up. That's not part of what I do. But I want you to know this: I don't speak Spanish, but I understand Spanish.' I didn't understand it at first. But what he was really saying to me is, 'I don't know the intricacies that it takes for your job, coaching the defensive line. but I understand the end result.'"

Everybody else understood who was the boss.

"There are a lot of things that make a particular coach successful," Wiggin said. "But the one thing that every successful coach has is command. ... We trusted everything he said."

Wiggin, who came to Minnesota from the West Coast, remembers talking to assistant Floyd Reese one day about the weather. Specifically about what the team did when lightning threatened practice.

"I said, 'What do you do?' " Wiggin recalled. "He said, 'Well, we go in.' I said, 'How do you know when it's time?' And Floyd just said, 'Bud knows.' "

For all the victories, many focus on the four Super Bowl losses the Vikings suffered. Not Grant.

"There are so many games," Grant said. "You have to be realistic. If the ball bounces the wrong way, if you have an injury. ... If you control everything you can control, then the things you can't control, you can't sweat those. ... The other team might be better than you."

One more year

After the 1983 season Grant decided to retire. It was a story reported by his friend, Hartman, a decision that came out of the blue. Grant got on a plane to go to Hawaii to tell Winter, and he had Sid come along. With the plane in the air, Grant gave Hartman the scoop.

"That was before they had telephones on airplanes," Grant said on the eve of his induction to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1994. "Sid asked for a parachute."

Instead, Hartman got off the plane while it refueled in California and crafted his story.

That retirement was short-lived. After a disastrous 3-13 season under Les Steckel, Winter and general manager Mike Lynn prevailed on Grant to return to put the franchise back on track.

Grant signed back on, in lucrative fashion. He got a lifetime contract with deferred money, a negotiated pact that shows just how many steps Grant was able to stay ahead of people. It included an office that guaranteed a window, (Grant had to pull out that contract when, years later, the head of the ownership group, Roger Headrick, tried to move Grant), and a gas allowance. Not to mention the understanding that Jerry Burns would take over as coach once Grant left.

The Vikings started the '85 season 2-0, then finished 7-9. Not spectacular, but back on track. After that season Grant retired again, this time for good.

He walked away having left an imprint on the game.