Allison Rian gently stuffs a sprouted acorn into a soil-filled plug in a plastic tray, then another.

Soaking acorns fill the kitchen sink. Trays of them sprout off the living room. Jars of yellow birch and white pine seeds chill inside the refrigerator.

"We've jumped into the deep end of the pool," said her husband, Scott Rian.

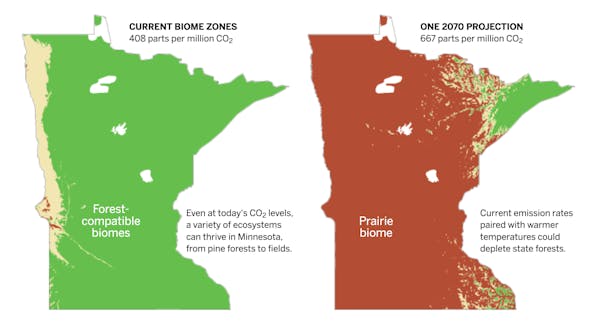

It's the family's first foray into forestry. With luck, most of the 10,500 tree seeds they're nursing in the converted sunroom of their old farmhouse near Aitkin will take root. They will be part of the first batch of climate-smart seedlings in a bold new effort to help Minnesota's northern forests handle the warming temperatures threatening to turn vast swathes of the state's forests into grass.

The Rians are part of a new Forest Assisted Migration Project, a grant-financed collaboration between the University of Minnesota, the Nature Conservancy and the Greater Mille Lacs Chapter of the Sustainable Farming Association of Minnesota. The five-year effort seeks to create a regional wholesale market for the types of tree seedlings northern forests will need to thrive — and fight climate change.

The five-year goal is to grow 1 million trees such as white pine, red oak and yellow birch, said project lead David Abazs, executive director of the U's Northeast Regional Sustainable Development Partnership. It's part solution, part adaptation, he said.

"If we do nothing we're going to be spotty forested in northeast Minnesota," Abazs said. "We have a rich wildlife habitat here that would be lost with a loss of forest."

The pilot project is part of a groundswell of reforestation efforts underway as people turn to trees — mighty consumers of carbon, a key greenhouse gas — as powerful tools in the race against global warming. Even Tazo Tea and the Minneapolis-area Rotary Clubs have projects to boost tree canopies.

Yet the production of seedlings across the U.S. has been dropping since the 1980s, said Joe Fargione, the Nature Conservancy's director of science for North America.

In a study published recently in the journal Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, Fargione and others argue the United States must radically scale up its production of tree seedlings and build supply chains to meet coming demand.

The pandemic — think toilet paper — has illustrated the vulnerabilities in other supply chains when demand rises, Fargione said. Trees are no different. The number one bottleneck, the study determined, was labor shortages at nurseries.

"It's underappreciated that even if people want to plant trees, they might not be available," he said.

Millions more trees

Currently, Minnesota produces 6.1 million tree seedlings a year, mostly by the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) at its nursery in Akeley.

According to Fargione's study, Minnesota could reforest 1.4 million acres with 784 million trees by 2040. Most of that land is currently pasture land and crops. The cost? More than $1 billion.

"I think that it is totally possible if we choose to invest in it," Fargione said. "2040 is a ways off."

The DNR has something more modest in mind.

The agency plans to double its production of bare-root tree seedlings to add 12 million more trees across Minnesota by 2025. That would help re-establish new forest cover and add density, said DNR Commissioner Sarah Strommen. It's requesting $2.6 million from the state for the next few years.

"The goal is to offset an additional 5 million tons of carbon dioxide by 2025," Strommen said.

That's far short of the kind of radical planting die-hard ecologists call for. But it's a start, Fargione said.

"That's exactly the kind of public investment that we need," he said.

The DNR is working out details such as the types of trees most needed. It's also figuring out the incentives it needs to create to encourage private land owners to plant. After all, most of the land available for adding forest cover in Minnesota is privately held.

Selling tree seedlings

Back at the Rian's farmhouse, they're learning as they go, mixing soil in an old cement mixer out back.

They're beginning vegetable farmers, and their AlliCat Farm supplies local businesses and farmers markets with produce such as potatoes, basil, peppers and garlic. The tree-growing is a leap of faith, one that fits with their belief in local production and shorter supply chains, Allison Rian said. Plus, farmers are always looking for ways to diversify their income.

They're one of more than a dozen farmers and nurseries growing seedlings for the pilot project.

The seeds were supplied by the University of Minnesota Duluth, which hired the seed collectors who fanned out across woodlots in central and southern Minnesota last year. They harvested nearly 400,000 seeds from five species: red oak, yellow birch, white pine, river birch and black cherry. More will be harvested each year.

Seeds from warming climates are growing better in the north, the U's Abazs said. The seeds from south and central Minnesota will outperform and outgrow tree seeds from northern Minnesota.

The pilot project's trees will help build more resilient forests and increase the canopy for a wide range of buyers' needs, from carbon sequestration and logging to conservation and wildlife habitat, Abazs said.

The Nature Conservancy has committed to buying 40,000 of the seedlings. Other customers include Carlton County Forestry, the Aitkin, Koochiching and Lake County Soil and Water Conservation Districts and Minnesota Power, which has an ongoing project to plant millions of white pine, red pine, jack pine and spruce trees on company land in northern Minnesota.

The Rians expect to fetch about $1 per oak and yellow birch seedling; 40 cents per white pine.

They're excited to see the experiment become a working supply chain — fingers crossed.

"We're not going to know if this is going to work for a couple of years," Allison Rian said. "If we can sell these trees, this is going to be the best day of my life."

jennifer.bjorhus@startribune.com 612-673-4683