As one of the nation's best walleye-fishing states, Minnesota is blessed with as many as 260 large lakes where the fish grow wild. Those waters naturally produce 85% of our annual harvest of more than 3 million walleyes. But to satisfy our collective craving for more walleye, state fisheries managers have been sweetening the pot in other lakes with stocked walleyes for more than 120 years.

If you catch a walleye this season on one of about 1,000 lakes enhanced by hatchery-raised fry or fingerlings, there's a good chance it was born in a jar. Here's a look at the life cycle of a stocked walleye:

Each April when wild walleyes gather to spawn, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) intercepts them at 12 locations as far south as Lake Sarah in Murray County and as far north as the Pike River at Lake Vermilion. Cut Foot Sioux Lake north of Deer River and Pine River near Brainerd are two other well-known sites.

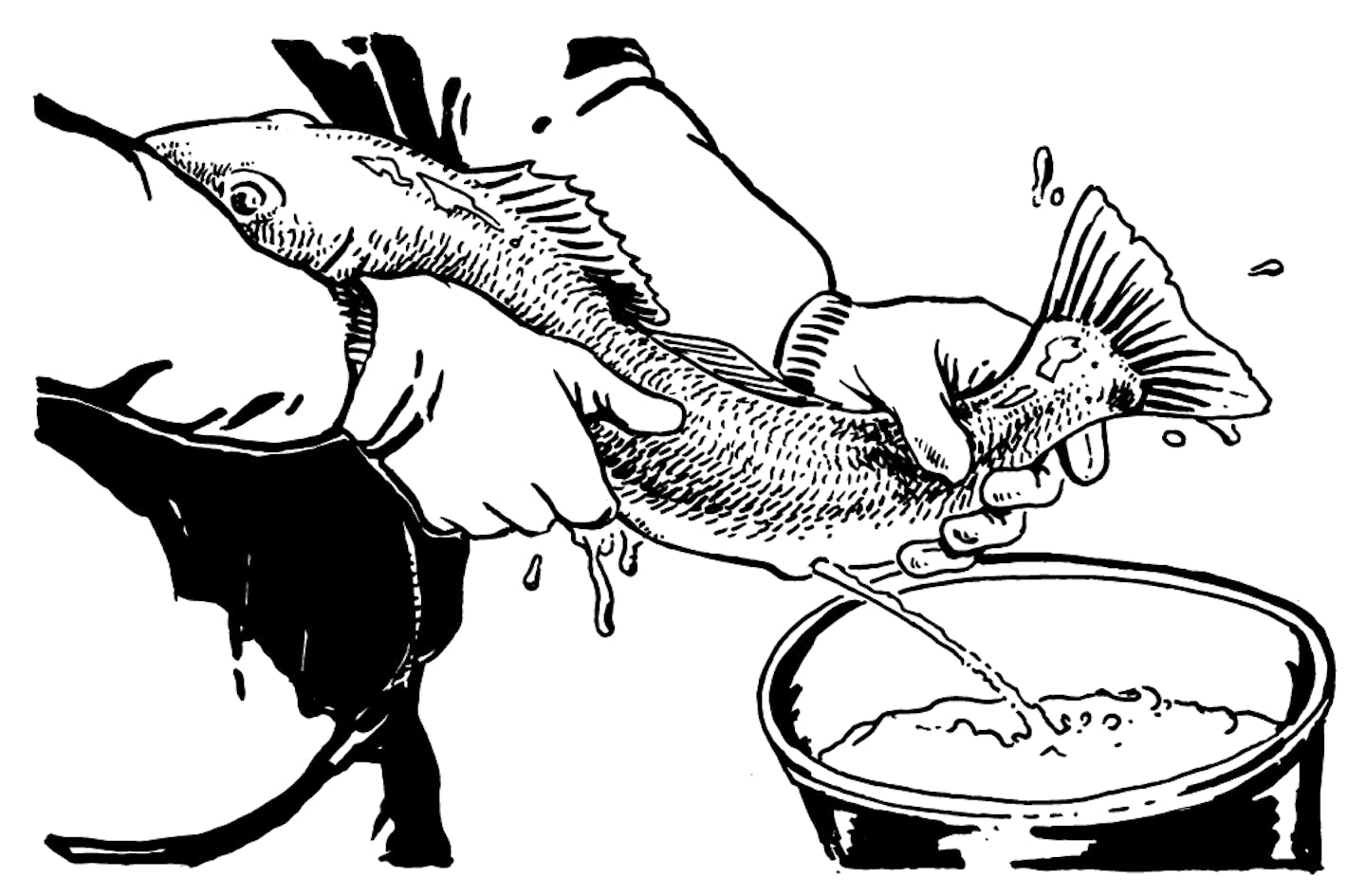

Crews at the stripping stations cradle male and female walleyes by hand, squeezing out gallons of milt and millions of yellowish eggs into plastic bowls. Workers swirl the gametes together and funnel them into an insulated stocking tank for transport by truck to one of 11 warm-water hatcheries around the state. The jars are engineered with supply lines that evenly distribute water to softly keep the fish eggs moving, mimicking spawning bed conditions in a lake.

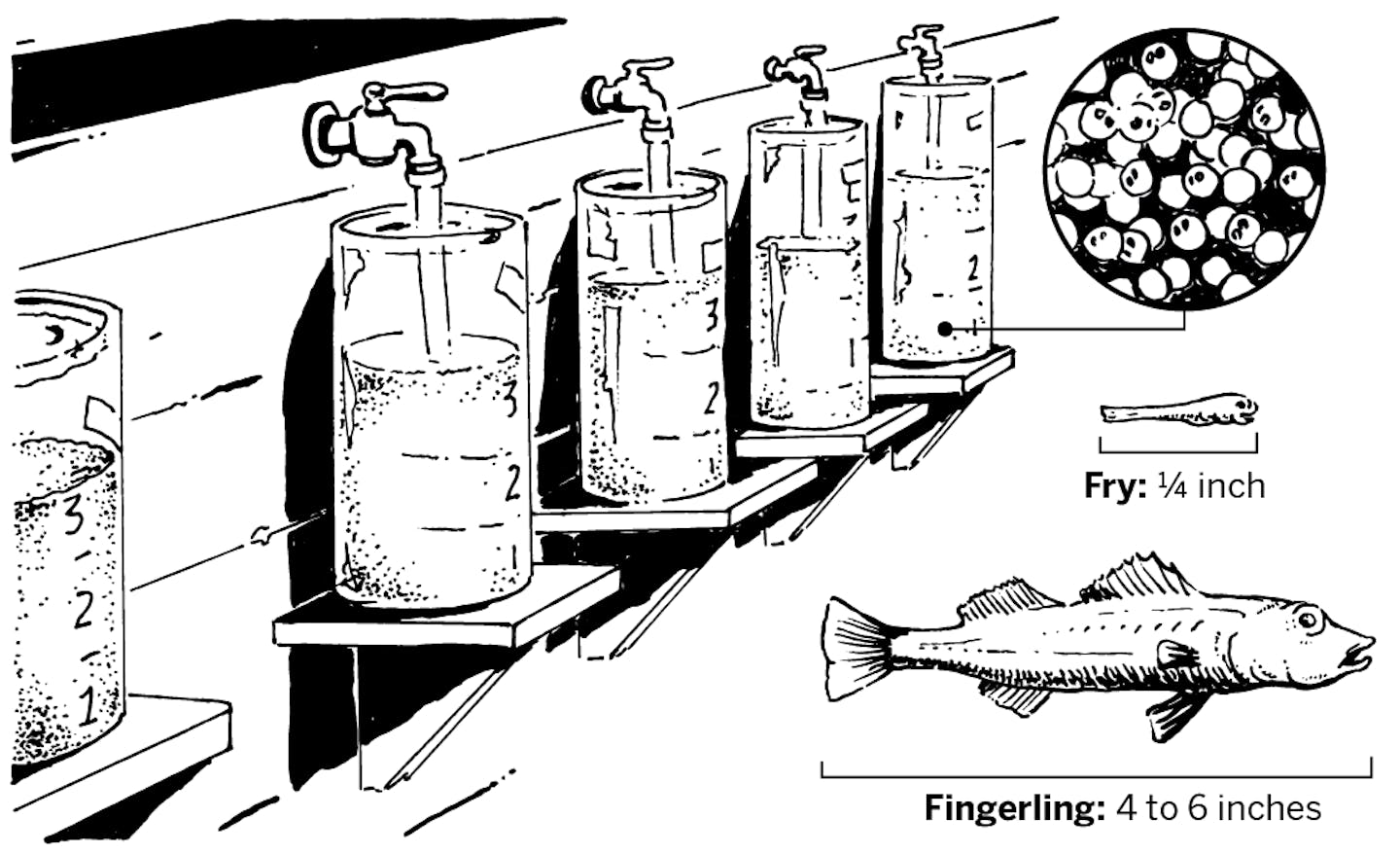

At the hatcheries, the fertilized eggs are transferred to calibrated jars where they are left to incubate for about two weeks. As soon as they hatch, the mosquito-sized walleyes are loaded into modified 5-gallon camp jugs — 100,000 fry to a container. The jugs are trucked to chosen lakes and released most often at a rate of 1,000 fry per littoral acre (the surface area of a lake where water is less than 15-feet deep). Generally speaking, managed lakes are stocked every other year, or less frequently depending on individualized lake plans.

A third of all fry don't go directly into lakes. At added expense, they are transported to 250 DNR rearing ponds for recapture in the fall. By then, the baby walleyes are 4- to 6-inch "fingerlings" — better-suited for stocking in lakes where walleye fry too readily get devoured by over-populations of sunfish and bass.

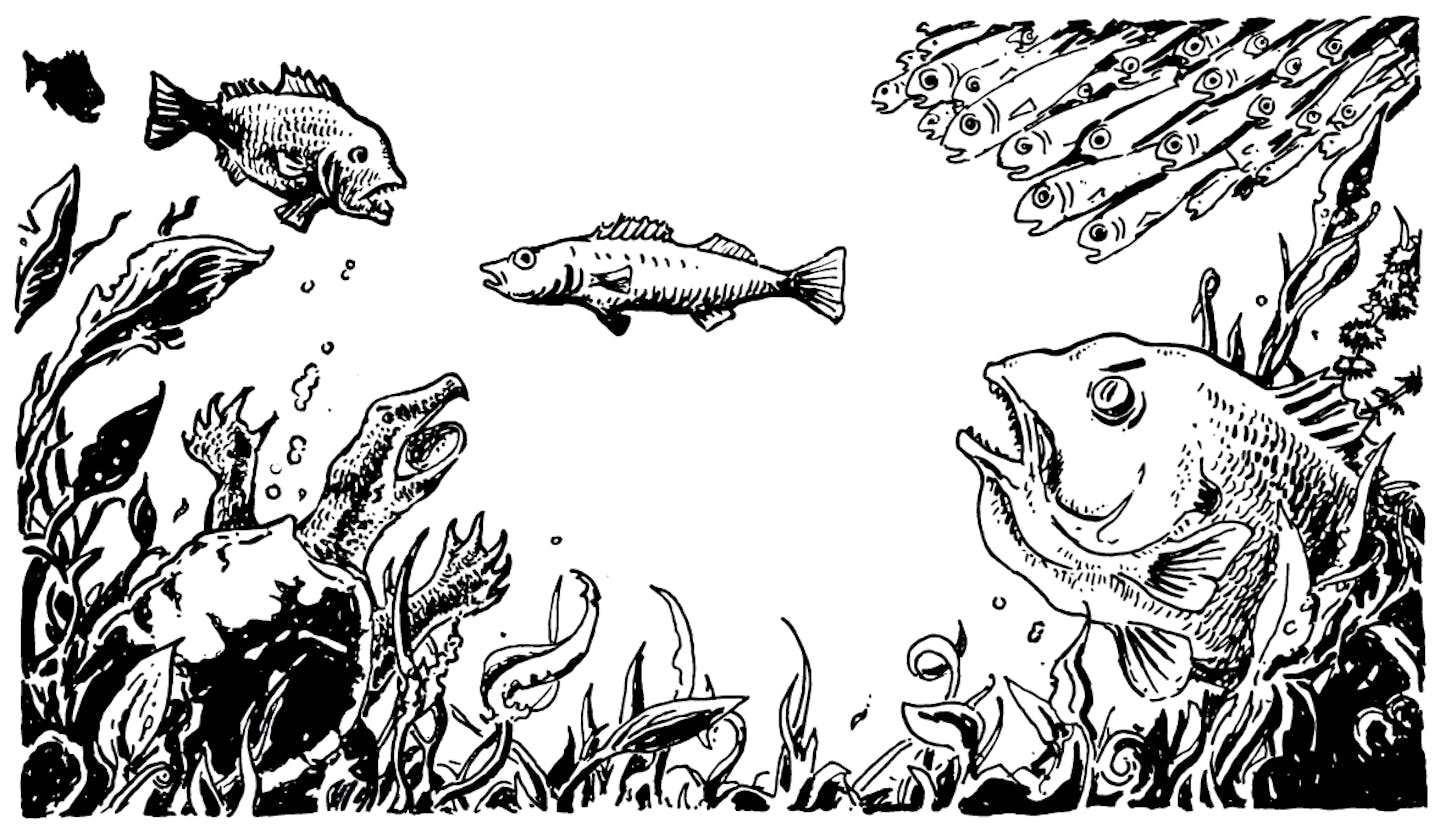

Even in lakes somewhat hospitable to walleye fry, only about 2% of the stocked babies survive longer than 18 months. Hungry minnows, small perch and small sunfish stand in their way. By 18 months, a walleye has matured into a fast swimmer and is too big to fit inside the gape of smallish predators.

It takes several years for stocked walleyes to reach one pound, or about 14 inches. Warmer, southern lakes have longer growing seasons, so walleyes grow to keeper size in those lakes in three to four years. At the northern border, the same growth takes five to six years. Of the approximately 3.5 million walleyes harvested every year by anglers, about half a million were stocked.

Sources: Minnesota DNR and "Walleye, A Beautiful Fish of the Dark" by Paul Radomski.