When Steve Perry decided to do his first extensive interview in more than 25 years, he flew into Minnesota to break radio silence with KQRS morning host Tom Barnard.

The former Journey-man’s choice may have startled those who have come to take the station and its megastar for granted. We forget that KQ helped revolutionize the airwaves, first by championing the rock format and, later, by turning Barnard into one of the most successful morning-drive personalities in FM history.

As the station celebrates its golden anniversary, we reached out to the DJs, programmers and musicians who led the charge. This is their story, in their own words.

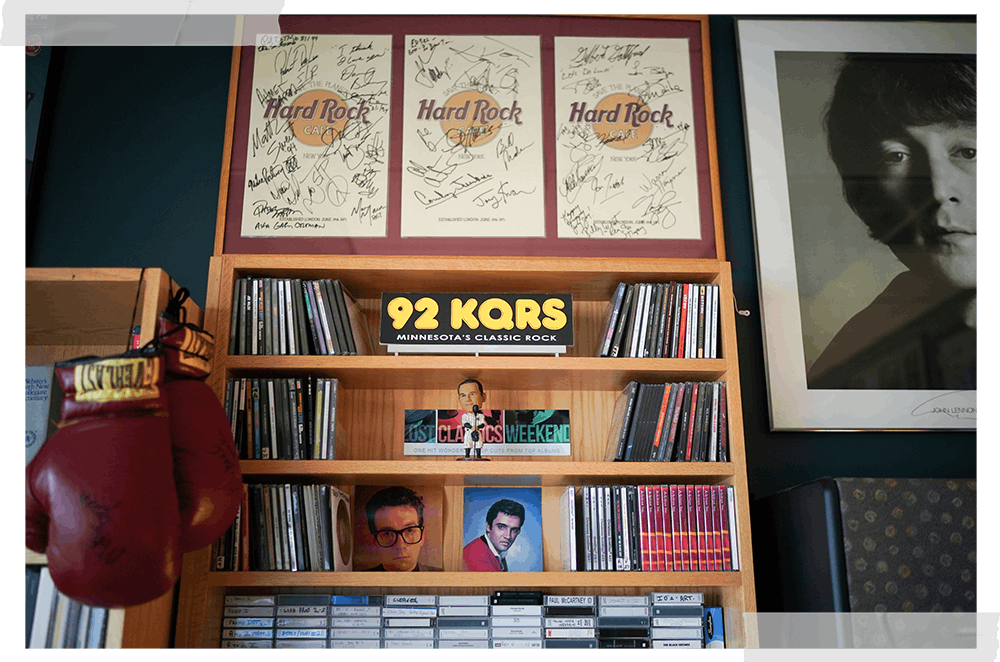

Music collection in the office of Operations Manager Scott Jameson. Photo by Glen Stubbe, Star Tribune.

Born to be wild

KQRS got its current call letters in 1964 and spent the next four years spinning mainly light pop-classical standards.

George Donaldson Fisher, DJ (1966-72): When I started it was a lot of “beautiful music” — Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra. We got sponsorship from [record-store chain] Musicland, which gave me like 300 albums, a lot of them from West Coast artists like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. Early in the broadcast, I had to play music that wasn’t too jarring, as we were segueing from big band and crooner stuff. After a while I could play whatever I wanted, even stuff with swear words in it.

Alan Stone (DJ, 1968-80; real name: Shel Danielson): I started pestering the program director, John Pete, to let me do what George was doing earlier in the evening. I felt like I could expand on the idea with my knowledge of jazz and blues. Albums like “Cheap Thrills” by Janis Joplin had only been out of a few months, so a lot of people didn’t know what was going on. We sort of invented it as we went along.

KQ in the early ’70s

Listen to a compilation of airtime from the early 1970s, featuring George Donaldson Fisher (1970), Russ (1972), Dan Pothier (1973), Randi Kirschbaum (1973) and Wayne Anthony (1973).

Wayne Selly (DJ and chief engineer, 1969-73): What George and Alan were doing at night, I eventually started doing during the day. I took out Dionne Warwick and Glen Campbell and put on Joe Cocker and Grand Funk Railroad.

Stone: We started getting letters from guys in prison. They weren’t asking for money. They just wanted us to play more B.B. King.

Fisher: The general manager said not to play drug music but a lot of it went over their heads, like Lee Michaels’ “Heighty Hi.” We were doing stuff like psychedelic comedy from Firesign Theatre and Pete Hamill’s “Massacre at My Lai.” Shel and I would counterprogram against the more traditional advertisers. When a jewelry ad ran, we would play a Grateful Dead song about sticking up a jewelry store [“Dupree’s Diamond Blues”]. The people who really wanted to advertise were head shops and record shops.

Jon Bream (longtime Star Tribune critic): In 1971, KQ broadcast a Grateful Dead/New Riders of the Purple Sage concert live from Northrop auditorium at the University of Minnesota. My pal Ed and I started his reel-to-reel tape deck at his Dinkytown apartment as the New Riders kicked off the night, walked over to Northrop, witnessed a great Dead show — the first gig for new keyboardist Keith Godchaux — and came back to relish a legendary tape, and experience in our lives.

Stone: A couple of years after I went on the air, I was driving the length of Lake Street on a hot summer night with the windows down. I could hear the radio station all across town from boomboxes and other cars when they pulled up next to me. That was a really great feeling.

Come together

During the days of Vietnam War protests, KQ was just as committed to spinning a socially conscious message as it was to music.

Selly: Alan and I would read draft numbers over the air [from a lottery held each year to determine who got called up for military service]. We found out later that kids over on campus were glued to radio waiting to hear the numbers announced. It was a pretty scary time.

Fisher: I don’t think we had anyone listening that was pro-war. There was one incident in which [President] Richard Nixon had authorized a nuclear test and, on a whim, we called the winter White House in Florida and asked if they had a [phone] listing for Nixon. They actually did and we gave it out on the air a few times. A couple hours later, the power was cut to the station. Someone had rammed a power pole with their car. We never knew if it was as accident or a reaction to our stunt.

Randi Kirshbaum (DJ, 1970-75): Alan Stone was the program director and I went to his office saying I thought a progressive station should have a woman on. I talked about the cultural relevance of Captain Beefheart. When he didn’t call me, I called him every week. I think I just wore him down until he gave me a show. I was 16 at the time. First day on air, I read a story about Henry Kissinger being voted the sexiest man alive by Playboy bunnies. I said, “Oh, that makes me want to puke.” Most of the people listening probably agreed with me.

Bill Tilton (host of the mid-’70s show “KQ Scope”): There was a minute in time when stations had public-affairs program requirements. I had just gotten out of jail [for destroying draft records] and was basically hired to be the news department. The programs we did on the legalization of marijuana were always popular ones; the lines were always full. I would periodically have an engineer from the department of transportation on to talk about when they were going to fix up Nicollet Avenue. Those were big ones.

Benjamin Mchie (DJ and host of a weekly show called “RAP”): We were on Sunday nights along with Bill’s show. Lots of interviews and commentary about the culture of African-Americans both locally and nationally. Sundays were kind of a ghetto in terms of ratings, but I think it was pretty good. On a scale of 1 to 10, I’d give us a strong 7.

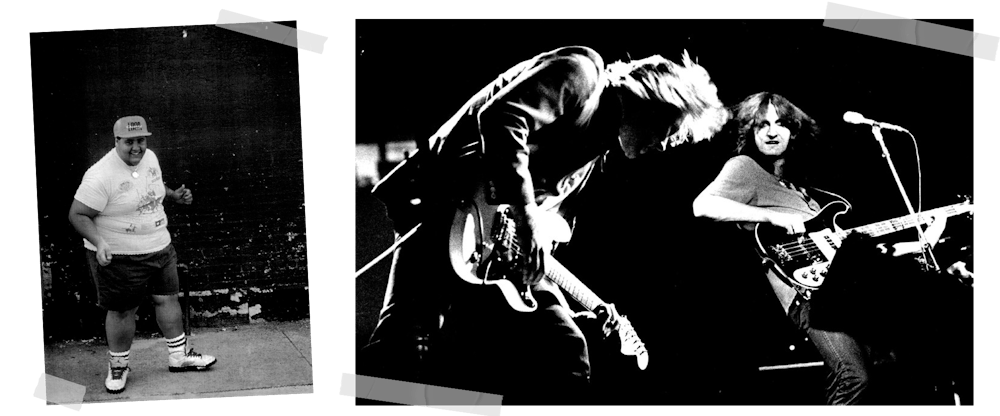

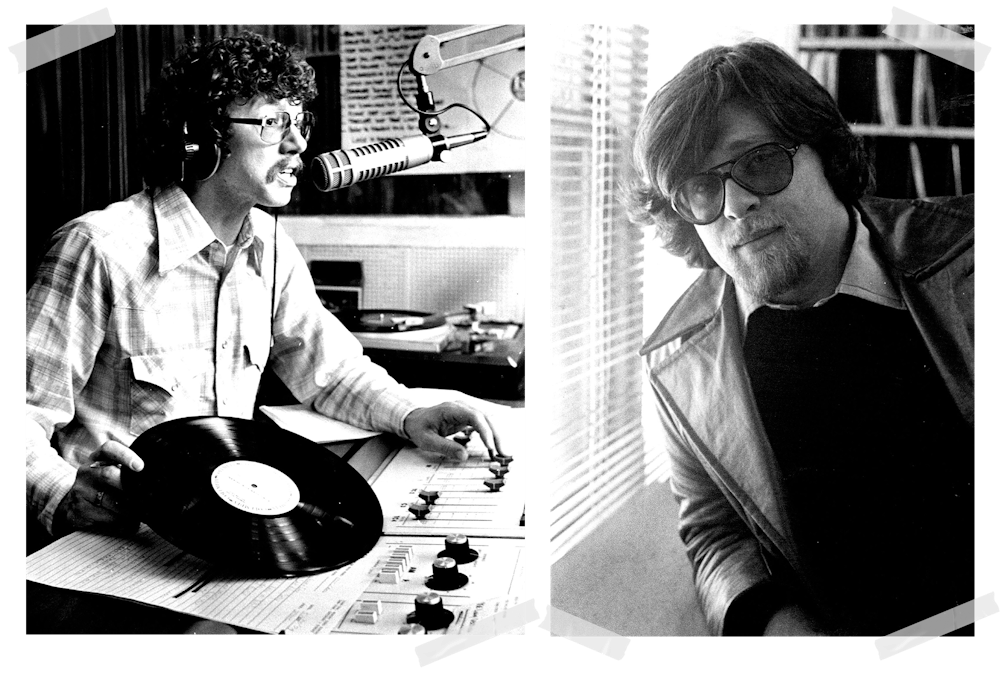

Left KQRS DJ Alan Stone plays music on June 8, 1979. Photo by Art Hager. Right KQRS DJ Tom Barnard stands for a portrait.

I want you to want me

KQ became an essential destination for musicians — and other entertainers — who wanted to make a mark in the Midwest.

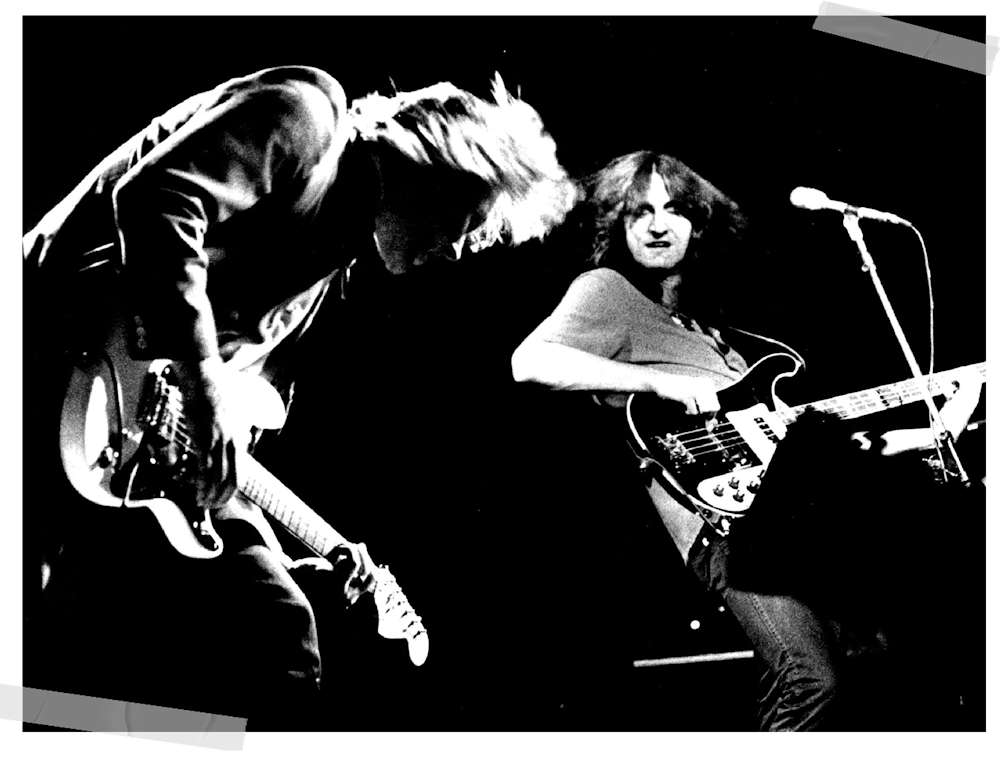

James Young (founding member of Styx): When we started off, Top 40 radio was very narrowly formatted. Stations like KQ embraced album rock as opposed to hit singles and that really opened the door for us to create ourselves. KQ was a slam dunk for us, in a way. My wife’s family was scattered throughout Minnesota and we always heard so much about the station from them and how much they were playing us.

Bob Seger (who'll play a KQ-sponsored 50th anniversary concert Thursday at Xcel Energy Center): From Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man to Live Bullet to today, KQRS has been there from day one.

Stone: One afternoon, I did an interview with Big Mama Thornton, followed by Doc Watson, followed by Leo Kottke. I think John Mayall was waiting outside, very unhappy. It was like a meat market: Take a number for better service.

Kirshbaum: First interview I ever did was with Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead. I think I said something really dumb like, “What’s it like being a rock star?”The benefit of being just 16 was that everyone was so nice to me.

Fisher: People would bang on the door on the middle of the night. One time, at about 2 a.m., Mike Love from the Beach Boys showed up and wondered if he could come in and sit down for a while. I think it was 1970. He picked out music and took calls. He was terrific.

KQ in the late ’70s

Listen to a compilation of airtime from the late 1970s, featuring Jim Larkin (1977), Alan Stone (1978), Kevin St. John (1978), Tac Hammer (1978) and Wally Walker, Dave Dworkin, Benjie McHie (covering the death of John Lennon, 1980).

Stone: Carlos Santana had finished a sound check and was bored, so his record guy called up and asked if he could come over to the station. We let him pick the music for two or three hours. He had pretty good taste.

John Lassman (DJ, 1983-94, and morning show producer since 2015): We had just passed a no-smoking ordinance after 30 years of smoking in the Golden Valley location. John Mellencamp came into the studio and lit up a Marlboro. I sad, “Sorry, John. You’re going to have to put that out.” He put it out and then said, “Can you get a soda?” I go down the hall and when I come back he’s smoking again. “John, you’re going to get me in trouble.” He said, “Listen, I can keep smoking and stay or I can put it out and leave.” I told him to keep smoking.

Wally Walker (DJ, 1979-present): I was working on a Sunday afternoon and Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth dropped by to chat. I don’t know what David was on that day, but Eddie kept him under control to some degree. Must have been their first or second album. At the time we had a nice little front lawn outside the studio and by the time they were done, a mini-Woodstock had formed out there. That spur-of-the-moment thing happened all the time back then.

Shawn Phillips (singer/songwriter): KQ was probably one of the most important sources for getting my music out for people to hear it. You could come into the studio and talk about anything. I remember people were particularly enamored with a story I told about driving back from Naples and seeing this perfect rainbow over the top of the mountain. You can’t talk about stuff like that on the radio today.

Beau Siegel (promotions manager for the Elektra/Asylum label and later RCA Records): There’s a certain amount of records KQ broke first: Greg Kihn Band’s “The Break Up Song.” The Georgia Satellites’ “Keep Your Hands to Yourself.” It was the most important station in the Twin Cities for breaking music.

Lassman: Chuck Berry was [in town] in 1987 and I was running around with a cassette desk backstage. I said, “Excuse me, Mr. Berry. Can we get a station ID? I’ve got it written out.” He said, “You ready? This is Chuck Berry and you’re listening to KQ 99.” I went, “That’s great, but let’s try again. It’s KQ 92.” He said, “You get one, son.” And he walked away.

Dave Hamilton (program director, 1985-2012): In 2004, John Fogerty was in town for a concert. He stopped by our studios for a visit along with his wife and young daughter. Over the years KQ had collected customized IDs from most of our classic rock artists, but John was notorious for turning down requests. We had a plan to divide and conquer. With our sister station Radio Disney in the building, a young woman in our promotions department offered to take John’s daughter down the hall to “see the Disney toys.” While John and his wife were cut off from their child, we talked them into allowing John to record an ID for us.

Ray Erick (DJ, 1989-present): I was set to interview Paul McCartney and was told someone would call me ahead of time with some rule. I was home making lunch and the phone rang. It was Paul. He said, “You can have me on as long as you want. Just make sure to cut me off first so it doesn’t look like I’m a snob and I’m too busy for you.’

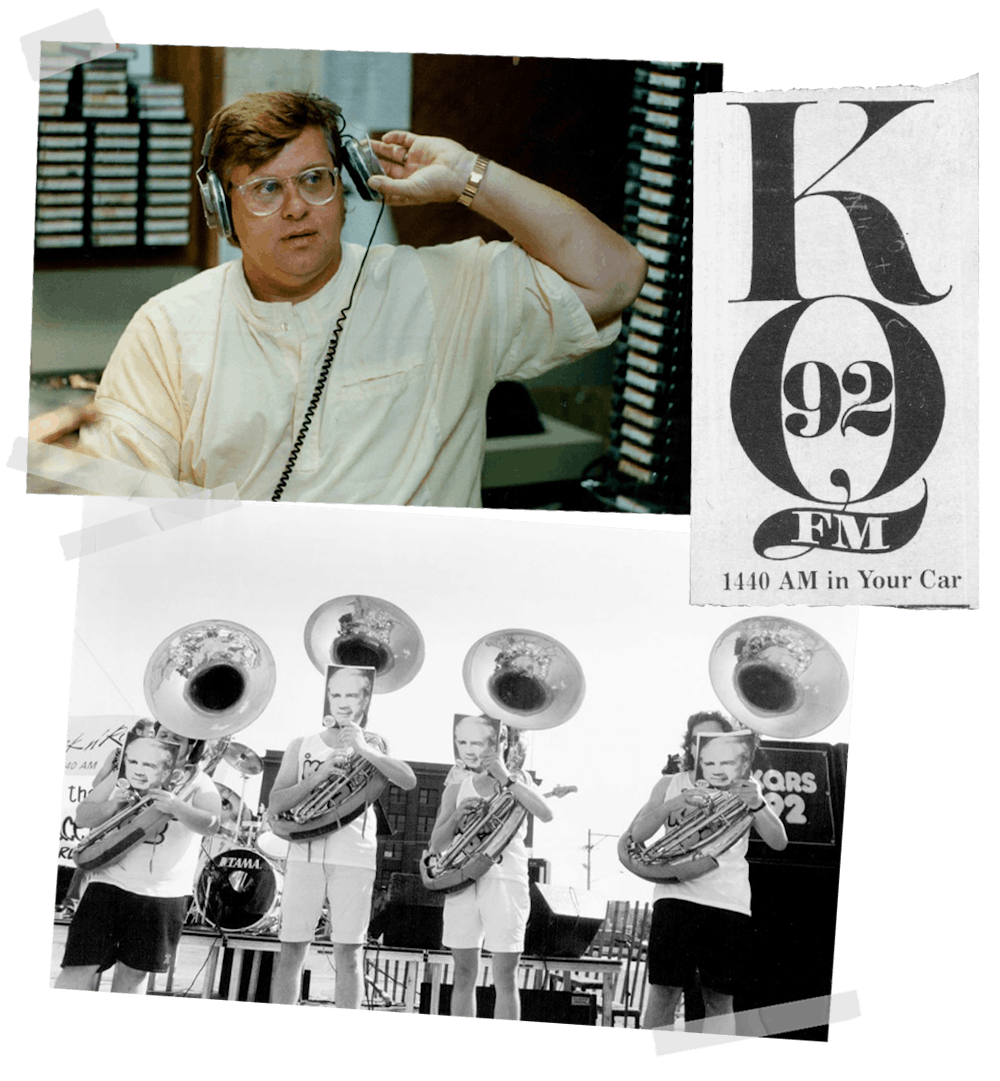

Tom Barnard at the mic in July 1988. Photo by Rich Sennott, Star Tribune.

When the whip comes down

In 1977, Abrams Media was hired as a consulting firm; DJs were quickly limited on what they could play.

Stone: It was like going from a chef-driven restaurant to a franchise operation. Where we were previously choosing from 1,000 albums we now had to choose from 800 songs. The creativity was gone. My guess is that Abrams told management that they would find another station that would carry their format and they would beat us. Too many people who had created the KQ sound were leaving and at the time the station was No. 2 or No. 3. There was pressure to build on that audience.

Mchie, who left the station in 1981: I wasn’t a big fan of the format coming in and eventually my interest in radio dwindled. You couldn’t break new music. You had to play what was on the Billboard charts.

Hamilton: Between 1985 and 2011, we spent around $100,000 per year in an effort to find the songs and artists our audience most wanted to hear and to mine for those “nugget” songs you wouldn’t hear anywhere else. We had a bank of callers who would play short “hooks” of songs over the phone to 75-100 KQ listeners each week. Some of the songs we dug up were “Little Guitars” by Van Halen, “Custard Pie” by Led Zeppelin and “Lightning Strikes” by Aerosmith.

Craig Finn (Edina-bred frontman for the Hold Steady): When you’re 16 or 17, you want to spend as little time at home as possible, so you spend it driving around listening to the radio. Back then, there weren’t any alt-rock stations. So it was classic rock, 92 KQRS. To this day, I can sing every song on classic-rock radio, and I never liked a lot of it.

Mei Young (overnight host, 1986-2006): I hosted a program called “Homegrown” for almost 10 years. On Sundays around midnight local bands would come in and play live. It would have been tough to get it on any earlier in the day. It was very corporate. But it was a way to give back to locals. I think it was good karma for the station. We had everyone on: the Suburbs, Trampled by Turtles, Haley Bonar. One night in 2000, Happy Apple joined Slug [of Atmosphere] on his song “In My Continental.” A jazz band with rap. Robyne Robinson happened to be in that night and even she got into that number.

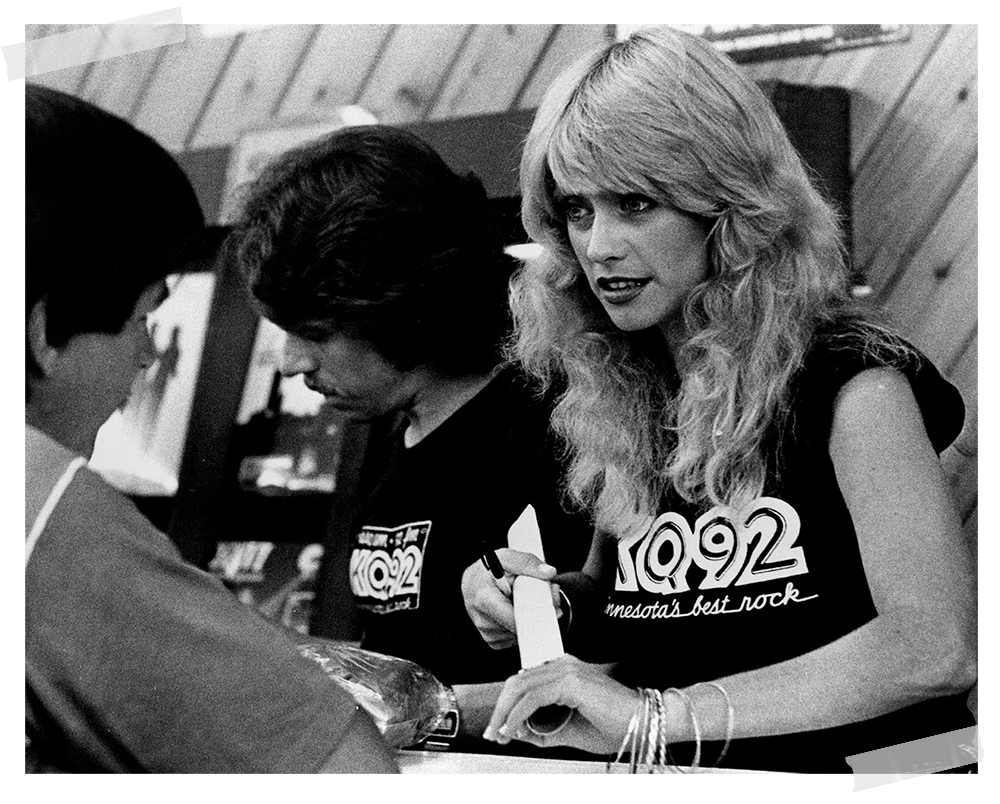

Lorelei Shark, a model who posed for ads for KQRS and other rock stations around the country, autographed posters for fans in 1980. Photo by Jack Gillis, Star Tribune.

We are the champions

In 1986, KQ signed a new consultant, Jacobs Media, which pushed for the classic-rock format that still exists today. But it was the hiring of Tom Barnard as morning host that same year that would trigger the station’s rise to the top. By 1994, it had toppled WCCO-AM from its perch as the Twin Cities’ most popular station and Barnard was the nation’s highest-rated morning radio host.

Hamilton: Ratings-wise, the station was in the middle of the pack. Half our audience was between 12 and 24, not a really desirable demographic. I realized I needed to boost the morning numbers if I wanted to stay employed.

Tom Barnard: I was doing voiceover work in New York and my wife called, told me she was going to have a baby. I thought, “We can’t raise a baby in Manhattan.” I put the phone down and Dave literally called moments later and asked if I had any interest in hosting a morning show. I said, “Yeah.” I didn’t even think about it much.

KQ in 1987

Listen to a compilation of airtime from 1987, featuring Jack Hicks, Wally Walker, John Lassman and Nancy Rosen.

Mark Rosen, WCCO sports anchor: I got to KQ before Barnard did. They put a line in my townhouse and I’d put my headset on and talk to some jock for these two- or three-minute sports updates. In March 1986, I got a call: “You ever heard of this guy named Tom Barnard? He starts tomorrow morning.” When I got on the air, something happened. I hadn’t even met him yet and he started ripping on me. That little sports update turned into 20- or 30-minute free-for-alls. I’m guessing it was a combination of our personalities. He gave me the exposure I had never had before, and I gave him the credibility he had never had before. It was the perfect mix. I ran for governor in ’86 and got 9,000 votes. We were just trying to raise money for the United Way, but college kids picked up on it. Back then, no one thought a celebrity could be governor. Jesse Ventura said he learned from me.

Scott Jameson (operations manager, 2012-present): Tom embracing the ’87 Twins has a multilevel story line. That’s when Tom exploded, that’s when the station exploded, that’s when the Twins exploded.

Barnard: Michael Jackson had called the station and said he wanted to be interviewed on the KQ morning show. Well, he canceled at the last minute. So, in that instant, John Lassman created “The Chucker.” He pulled out a Chicago phone book, found a guy named Michael Jackson and called him in this voice he just made up. That’s how the whole prank thing started.

Hamilton: Tom was polarizing right out of the chute, but he connected with a large portion of our listeners. We were getting complaints, but more than anything they were about too much talking and not enough playing music.

Barnard: Andy Rooney did not want to do an interview. Morning crew member Mike Gelfand asked a question, and Rooney said, “Oh, it takes two of you to do this show?” I said, “Andy, maybe we should call you another time.” He said, “What about never?” I said, “What about you’re a flaming (expletive)” and hung up on him. I’ve never been one to put up with that kind of thing.

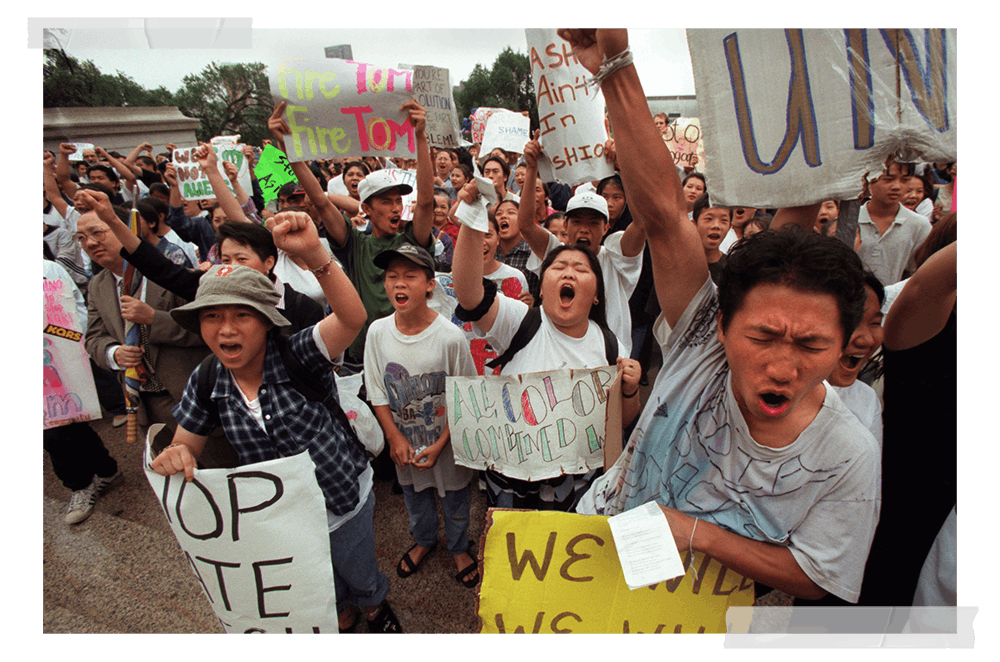

Protesters yelled out chants during a 1998 rally on the State Capitol steps, sparked by derogatory comments that Tom Barnard made about Hmong people. Several companies pulled ads from the morning show, and KQRS management ultimately issued an apology. Photo by Bruce Bisping, Star Tribune.

Ridin’ the storm out

At times, the jokes and commentary crossed the line, at least to the ears of some community members. Native Americans, the Hmong community and Somali cabdrivers would each stage protests demanding apologies and even Barnard’s resignation.

Erick: About 4 p.m. I was on the air and I was told about a hundred cabdrivers were heading my way. They surrounded the building. They had to close off a whole section of Golden Valley. Nobody could leave.

Noel Holston (Star Tribune TV/radio critic, 1986-2000): At some point, the jokes and sketches got meaner and more sexist and homophobic and racist. It seemed as though Barnard had started to see himself as the voice of the threatened white male. I think the bit that made me speak up in the paper was the riffing they did one morning about a rape case that involved Hmong immigrants, both underage. I thought they really crossed a line of decency. I got a lot of cheers from readers who considered Barnard a jerk. I also got some hate letters and a ton of hostile voice mails at work from Barnard fans, several of whom threatened me with bodily harm. I sawed off one of my old baseball bats and carried it in my backpack for several weeks.

Barnard: Why people get so emotional about a radio show is amazing to me. You guys think I’m mad at everybody. I’m not.

An even bigger threat came in 1997 when rival station Rock 100 (now KFAN) decided to bring Howard Stern’s syndicated morning show to the Twin Cities. The so-called King of All Media gave up after two years.

Hamilton: We realized Howard was starting to spread himself very thin and that the magic was starting to wear off. We saw how other stations dealt with him coming into their market and had a blueprint on how to win: Ignore him and be edgier. During his first days in the market, we had a live event called Flogapalooza, an S&M deal with the most notorious dominatrix in the Midwest. Who’s edgy now?

Barnard: I don’t have anything against Howard. I’ve never even met Howard. He’s just not very good on the air.

Hamilton: About six months after Stern came to the market, the KQ morning show was involved in another controversy which resulted in a protest/demonstration at our studios. The whole thing got lots of coverage by local TV news and print media. Andy Bloom, the program director at Rock 100, was beginning to realize he was losing the war. In desperation, he called Stern and asked to be put on the air live. I happened to punch over to 100.3 that morning and heard Bloom pleading with Stern: “Howard, we’re getting outmaneuvered here. Please get me a protest in Minnesota.” Stern replied, “Why should I care what happens in Minnesota? Gary, get this guy off the phone!”

KQRS put on mass weddings at the Mall of America. In 1994, 92 couples were joined in marriage, live on the air. Left photo by Joey McLeister, right photo by Charles Bjorgen.

Runnin’ with the devil

KQ became known for its wacky promotions.

Selly: There was this Let’s Go Fly a Kite thing at Lake Nokomis. Ten thousand people showed up to fly a kite. What the hell were all those people doing there?

Lassman: There was a Twins pitcher holding out for more dough. Everybody hated this guy. We got a big hopper and invited listeners to come down to Golden Valley to throw pennies in this big hopper. Well, the hopper started filling up. People were lined up down the street.

Erick: We got a hold of some Suzuki Samurais in the late ’80s. Right before we were going to give them away, this story came out that they were dangerous and could flip over. We decided to promote the contest with audio of women screaming in terror. Eventually, we offered $10,000 cash options instead of the motorcycles, but some people still chose the Samurais.

Walker: One time in the late ’80s, after I had had a couple kids, Dave Hamilton asked if I was thinking about having a vasectomy. He said that he could get me a free one if I had it on Tom’s show. Mike Gelfand provided play-by-play. He got the idea from a station in Chicago, but I think I was the second person to ever have a live vasectomy on the air.

Erick: In 1994, we officiated the marriage of 92 couples in the Rotunda in the Mall of America, live on the air. I still run into people from that event. Still married.

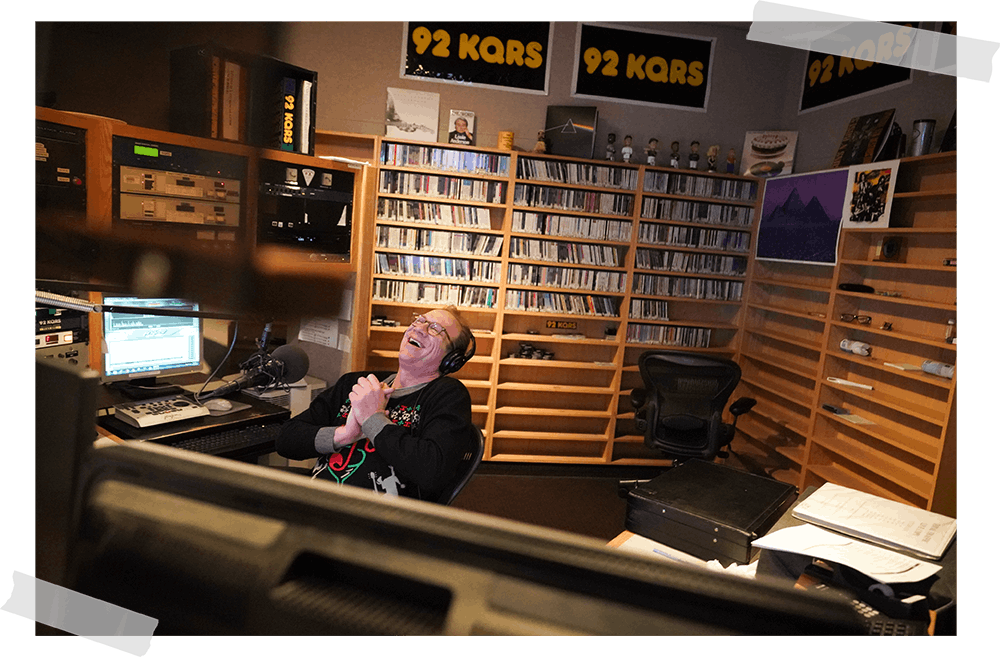

John Lassman, executive producer of the KQRS morning show, laughs during a recent broadcast. Photo by Glen Stubbe, Star Tribune.

Old time rock and roll

While ratings for Barnard remain strong, the rest of the lineup has taken a hit in recent years. According to the latest Nielsen ratings, KQ is eighth in the market.

Jameson: I believe the future of KQ based on how media consumption is valued by advertisers. In 2019, the youngest baby boomer will turn 55. Why is that significant? Because the demographic that Nielsen sees as valuable consumers is 25-54. That’s extraordinarily crazy. Advertisers have to recognize the robust spending power and household wealth of the alpha-boomer generation. You can adjust your vintage to younger people, but that’s very dangerous. Our audience expects a certain sound.

Fisher: It was sad to see it become a corporate station. These days, the only station I’ll listen to is the Current. They’re doing something similar to what we did.

Walker: I think you’ll start to hear less things from the late ’60s and more songs from the ’80s. We’ve been playing more Guns N’ Roses and Motley Crue.

Jameson: When the Beatles put their music on iTunes, there was a seismic shift to that younger generation. That type of music is also getting a second wind from kids downloading “Guitar Hero.” But in terms of raw numbers, I’m not sure they listen that much. It’s still about the music you grew up with. That’s where you have the emotional connection.

Louie Anderson: Radio is still the best social media that we’ve got. I just did a morning show in Los Angeles to promote my appearance at a comedy club and ticket sales doubled. KQRS — Tommy B — is still the best of the country’s morning shows that I’ve been on. I can’t thank them enough. I get choked up even talking about it.

Lisa Miller (DJ, 1993-present): I’m no Obi Wan Music Kenobi. If people want to hear “Gimme Shelter” again, who am I to judge? KQ is synonymous with Minnesota and synonymous with home. We’re familiar. We’re your friends on the radio.