TULSA, OKLA. — Standing in the doorway, I heard Bob Dylan's voice in the distance. His words beckoned me to turn the corner, then I realized: There were no other visitors at the Bob Dylan Center.

It was the day before the May 10 opening of the $10 million new museum/archive, where his voice was emanating from a splashy, multi-screen installation to an audience of exactly one.

A rare commemoration for a living — and still working — artist, the center is called the "BDC" on T-shirts and hoodies. How bland. And confusing. (CBD?) This grand place needs an appellation that sings — how about "The Bob"?

I was having a solitary experience at The Bob, not unlike the way I engage with his recordings. Absorbing lyrics, responding to the rhythm or melody, lost in my thoughts.

How does it feel to be on your own, amid two stories of Bobness?

Immersive and exclusive. Overwhelming. There was pride, too — that one of our own had dreams and visions he couldn't realize in the Land of 10,000 Lakes, so he reached out to the world. Now the living legend, who turns 81 Tuesday, has left us with tens of thousands of items from his personal archives.

What a saver he's been: Artifacts like the leather jacket he wore when he went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Priceless ephemera like a 1964 letter of admiration from Johnny Cash and a postcard of apology from Pete Seeger. And oddities like the autographs he reluctantly signed for a 1981 band member three wiseass ways — with his right hand, left hand and pen in his mouth.

There are four drafts of his first book, "Tarantula," and three pocket-size notebooks with lyrics for 1975's "Blood on the Tracks" — the kind of items that will draw Dylanologists to Tulsa. Some are on display, others available by appointment in the archives (with white gloves).

The center's 29,000 square feet are packed with Bobabilia: performance footage and interviews, posters and paintings, articles and essays, bootleg LPs and outtakes. Just no Grammys or trophies of any kind.

That's Dylan: Put him on a pedestal but don't treat him like he's on it.

Minnesota contributors

The new spot is in an old brick warehouse on a street named Reconciliation Way, two doors down from the Woody Guthrie Center in this once-booming oil city known for such musicians as Bob Wills, the Gap Band and Leon Russell.

For three days before the official opening, I dove into a sea of Bob along with other VIP visitors.

There was Dick Cohn of St. Paul, who has known Dylan since they were 14-year-olds at Herzl Camp in Webster. Wis.

"I think I took that picture!" Cohn beamed as he pointed to a snapshot of Herzl campers, including his buddies Larry Kegan and Bobby Zimmerman (now Dylan) with a guitar.

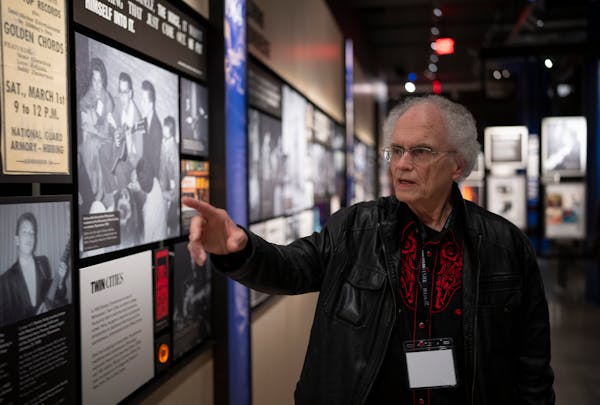

There was Bill Pagel, the obsessive Dylan collector who bought the singer's childhood homes in Duluth and Hibbing, where Pagel now lives. He guided me through The Bob, pointing out items from his massive collection. There's a blowup of a matchbook from the 10 O'Clock Scholar, a Minneapolis coffeehouse where Dylan played in 1959-60; a 1978 Dylan tour jacket, and a photo of his own great-niece reading a kids' book about Dylan.

Pagel is especially fond of his surreptitious Super-8 film of Dylan at a 1980 concert, roaring through "The Groom's Still Waiting at the Altar" in San Francisco with guest guitarist Mike Bloomfield, who died three months later.

"The film ran out and I had to put in another film," Pagel remembered. "Fortunately, at the end, [Bloomfield] walks over to Bob and gives him a hug. And I got that."

There was Kevin Odegard, a proud Minnesotan who, in a simple twist of fate, played on Dylan's landmark "Blood on the Tracks" sessions in Minneapolis in December 1974. The acoustic guitar Odegard strummed on "Tangled Up in Blue" — and his gold plaque for the album — are on display at The Bob.

"I was the outlier in my small town of Princeton," Odegard said as he stood next to his framed guitar. "I got Bob right away. He's an older version of the kid I felt inside of me."

On this weekend, Mark Davidson was masked and wired. As chief archivist and curator, he's been researching and collecting items ever since Dylan sold his personal archives in 2016 for a reported $20 million to the George Kaiser Family Foundation to establish this center.

"As much as Bob sort of distanced himself from [his early life], it's a thread that shoots through his work," Davidson said. "When I think of the Upper Midwest, I think of people who are not showy, don't mince words and have an ethical sense of what work means. They're diligent and hardworking and dedicated to their craft."

Venerable singer Taj Mahal paused at the exhibit for "Like a Rolling Stone."

"You heard the songs, you saw them in concert, you got to read some stuff in Rolling Stone or Crawdaddy or Spin or Mojo," Mahal told me, "but this stuff is invaluable because it expands what you know about a person."

Immersive experiences

Who's that kid with a Will Rogers hat and Buddy Holly glasses, reading a book by the stairway?

Max Nobel, a recent college grad, was helping to promote the center's reading alcove, curated by U.S. poet laureate Joy Harjo. She's selected "Moby Dick," "Grapes of Wrath," collections by Allen Ginsberg and James Baldwin, and all kinds of books about Bob, including "Dylanologists," Nobel's choice on this day.

Author Lewis Hyde saw his own book "The Gift" on the shelves. A retired professor and a University of Minnesota graduate, he has a few things to say about that school's most famous dropout.

"Fame is not his friend," Hyde observed. "He is not interested in the history of his career. This is a snapshot of 70 years of hard work."

Or as a quote from Dylan himself declares on a wall: "Life isn't about finding yourself or finding anything. Life is about creating yourself and creating things."

Hyde curated an exhibit on creativity that showcases vintage photos by Jerry Schatzberg, including powerful portraits of Aretha Franklin, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones in drag and, of course, Dylan. Schatzberg shot the cover of "Blonde on Blonde," Dylan's revered 1966 double album.

Rock Hall of Famer Elvis Costello, who performed as part of the opening festivities, programmed an interactive jukebox featuring 162 songs by Dylan, his influences and interpreters. Chatting with a handful of music journalists, Costello said he once discussed songwriting with Dylan at a party in the Minneapolis loft of video maker Chuck Statler, circa 1982.

Costello told Dylan he was concerned about fame preventing him from fading into the background to observe people — a necessity in songwriting. "I was naïve enough to ask that," he recounted. "It was nice that he took the time. I don't remember what he said, but it was so weird because everybody in the room was getting quieter and quieter and trying to listen, and then everything stopped and Bob said, 'I gotta go.'"

Another visitor to the center, Minnesota singer-songwriter and Dylan pal Gene LaFond, recalls that party, too: "Bob must have stayed for two hours talking to Elvis. Two of his kids were with him and they knew to hide under a table."

There is plenty of stuff for kids at The Bob. They might dig the interactive devices that play music and interviews, and a remarkable digital display that flips through drafts of "Tangled Up in Blue."

In a re-creation of a recording studio, visitors can listen to Dylan talking to his producers and musicians during sessions. You can hear multiple approaches to the song "Mississippi" and play engineer, adjusting the volume for vocals and various instruments.

All this and more for $12 ($10 for students and people 55 and older; free for 17 and younger) — a modest fee for a museum.

A few quibbles: The first-floor history timeline is too heavy on enlarged reproductions instead of original artifacts. A mere three explanatory kiosks for 92 uncaptioned displays on the second-floor archive wall are not practical; a printed list should be provided. More seats for tired museum legs would be welcome, too.

Two Bob-goers who had no complaints were Barry Duffy and Lauren Sheffer, opening-day visitors in T-shirts proclaiming their Gopher State roots.

"I loved the interactiveness of the whole center," said Duffy, now retired to Florida. "And I love how Dylan was never satisfied. He was always striving."

"Always creating," Sheffer interjected.

"We just scratched the surface in two hours," he said.

"We're definitely going to come back," she said.

Me, too.