The letter arrived at photographer Alec Soth's studio in St. Paul early this year.

"Please forgive the audacity of this letter," it started. "I reach out in great admiration and respect. For years, I have relied on photography for reference material, given my incarceration, and have developed a great admiration for the genre."

Soth, an internationally known artist, gets loads of e-mails and so many direct messages that "it's a problem," he said recently via Zoom. But he was struck by this letter, signed C. Fausto Cabrera. Its careful cursive, its thoughtful tone. And its origins — the Rush City Correctional Facility.

"Oh, that's interesting," Soth remembers thinking.

So he wrote back, launching a correspondence and a friendship that continue today. Nine months of letters and e-mails between Soth and Cabrera — about art and isolation, justice and redemption — are collected in a new book, "The Parameters of Our Cage."

Its title comes from Cabrera, who in addition to being an inmate is also a visual artist and writer. Proceeds from the book will be donated to the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, a nonprofit that leads classes in every state-run adult corrections facility.

"We all confront the parameters of our cage eventually," Cabrera told Soth early on. "What we do when we reach those bars helps define us."

How we define ourselves and others is a frequent topic in this personal, philosophical dialogue that is punctuated by photographs — both real and imagined — a few of which managed to make their way to Cabrera despite restrictions around mail and personal property.

Soth said their dialogue "was of enormous value to me, both as an artist and as an American citizen in 2020." But he wasn't sure it would work as a book. So he shared an early manuscript with his London-based publisher, who loved it.

He didn't tell Cabrera about the possibility of a book until after getting that feedback, not wanting to get him overly excited.

In an e-mail, Cabrera described his relationship with Soth as a "kindred connection" that has enriched his life.

"But beyond that, Alec has empowered me to see past my incarceration as an identity," Cabrera said. "He reminds me that I am an artist who has traversed traumatic terrain but has emerged stronger; and that I have a lot more to say and do."

Soth, too, describes being transformed by their dialogue, which itself was shaped by a cataclysmic year. "The world exploded in 15 different ways," he said.

As the pandemic shrunk his circle, Soth thought of Cabrera, in a small cell. As he biked past 38th Street and Chicago Avenue, Soth thought of Cabrera's breakdown of the term "justice."

"For years now I've watched these absurd killings by police from a cell," Cabrera wrote in late May. "Then people cry out for 'justice' like we even have a grasp on what that means.

"What they mean is prison, because that's what we've been trained to believe accountability looks like."

Redeeming a destructive past

In a way, it began with a black-and-white photograph.

One of Soth's, on the cover of a poetry collection Cabrera was reading, of a makeshift knife, rusty and wired. Cabrera jotted down Soth's name, then wrote a poem, "All I Know About Prison Shanks," which opens with:

"It doesn't have to look strong; it has to be strong."

Since being transferred to Rush City three years ago, Cabrera has missed the artistic community at the Stillwater prison, where he co-founded a writers group. He knew Soth was local, so he decided to write.

Cabrera believes "there was an element of destiny involved. ... We talk about art being a form of communication, and when it's infused with the soul of the artist it can reverberate out into the world at a frequency people connect with. It can make people feel like they already 'know' an artist even though it's been a kind of one-way transaction."

Soth's reply, on a postcard of a photo from his series "Sleeping by the Mississippi," made Cabrera giddy.

Soth asked a handful of questions, noting his fascination with "the relationship of photography to the lack of freedom."

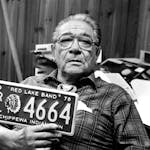

A few letters in, without being asked, Cabrera told him about why he's been incarcerated since 2003 — and likely will be until 2030.

"One night, I'm drunk and high and I go into the Stardust bar (now Memory Lanes) with my dirtbag big brother and get into a fight over some girl," he writes. A security guard Maced him, and things escalated.

"I recklessly shot up their car," Cabrera writes. "The man who had the least to do with it was killed. It was all bad."

Cabrera was convicted of first-degree murder in the death of Terrance Ringgold but, because of "the prosecutor's improper injection of race into closing arguments," according to a Minnesota Supreme Court decision, he got a new trial. In 2006, he pleaded guilty to second-degree intentional murder and four counts of attempted first-degree murder.

"Part of my responsibility is going to be about finding ways to pay forward on an insurmountable debt," Cabrera, who recently turned 40, said by e-mail last week. "Redemption isn't a destination, it is a lifelong journey for me."

He sees writing as a path toward dignity: "What can combat a destructive past more than a creative future?"

But in his present, he wakes up each day in a cell. Correctional officers "continuously remind me that I am a terrible person." At Stillwater, he ordered books and DVDs, collected art in three-ring binders. But at Rush City, all his property must fit in a 2-foot locker.

The power of imagination

Early in their correspondence, Soth asked: "Can you describe the eight photographs you might take to a desert island?"

Cabrera described a photo of his mother and an imagined scene featuring Demi Lovato in a cluttered room, surrounded by "photos, notebooks, talismans infused with their own nostalgia, things I could pore over to figure out what they say about her journey."

Then he described a setting — his aunt and uncle's hobby farm in Isanti, Minn. A summer's day at the property, "with enough of the sky and surrounding nature to capture the outdoorsy element of the landscape."

Soth was struck by the detail.

"One of the things that came out of it was how valuable the internal imagination is versus photographs of the external world," he said. Cabrera's rendering "was so much richer than photographs could ever be."

Inspired, Soth created a competition, enlisting his more than 200,000 Instagram followers to Photoshop the Demi Lovato image in Cabrera's mind.

Cabrera has never experienced social media, never dug into the limitlessness of the internet, while Soth tracks his own creativity closely to the internet's rise. "Even just writing a letter takes a lot of time," he said. "It's a different way of thinking. That part of my brain has atrophied from stupid culture."

Still, in their letters, the two share reference points. A poem leads to an image, which leads to a book, which leads to a lyric. And so on.

During a live conversation last month put on by the book's publisher, Cabrera was on the line from Rush City with Soth, on Zoom. Mid-talk, Cabrera mentioned Minnesota poet Jim Moore.

"I know Jim pretty well, actually," Soth said.

"Do you really?" Cabrera replied, his voice full of excitement. "Oh, that just opened a whole new layer! He was one of the founding poets who really shaped my voice." As Soth listened, his eyes closed, Cabrera described an interview in which Moore talked about the elements that make a great poet, including finding yourself in an odd environment and having a sense of brokenness.

"Wow, that's beautiful," Soth said.

"That's a whole layer we've got to dig into ... " Cabrera replied.

"Right! And this is what our exchange is about, I think, is that kind of thing ... " Soth said.

Before he could continue, an automated voice interrupted: "You have one minute remaining."

Respect turns to friendship

In the book, the artists' notes to one another grow longer, their signoffs more intimate. "Much respect," gives way to "Your friend" and "Much love."

Soth is aware of how different Cabrera's life is from his own. How someone might think he, a white man, is exploiting this connection with Cabrera, a person of color. Or how his own attempts to grapple with race and the Black Lives Matter movement outside his door could feel false.

But the respect the artists have for each other is evident throughout the book, which Soth estimates contains just a tenth of the pair's correspondence.

The two continue to write. These days, they also talk by phone, a means of communicating that used to stress out Soth. "I'm like, adapting," he said with a crooked grin.

That day, Soth was sitting on a "big fat" letter that had just arrived, which Soth knew would contain Cabrera's thoughts on God.

Even before social distancing was a thing, Soth described his work in terms of distance. In one letter, he told Cabrera: "My ideal distance for making a portrait is about the length of a seesaw — close enough to exchange energy, but far enough to properly visualize separateness."

One day, he decided to create another of his friend's images, driving to Cabrera's aunt and uncle's farm in Isanti. He set up a ladder and photographed Cabrera's loved ones from afar.

The resulting image, of a family at a picnic table framed by trees, has a soft, hazy light. A still from someone's dream.

Jenna Ross • 612-673-7168 • @ByJenna