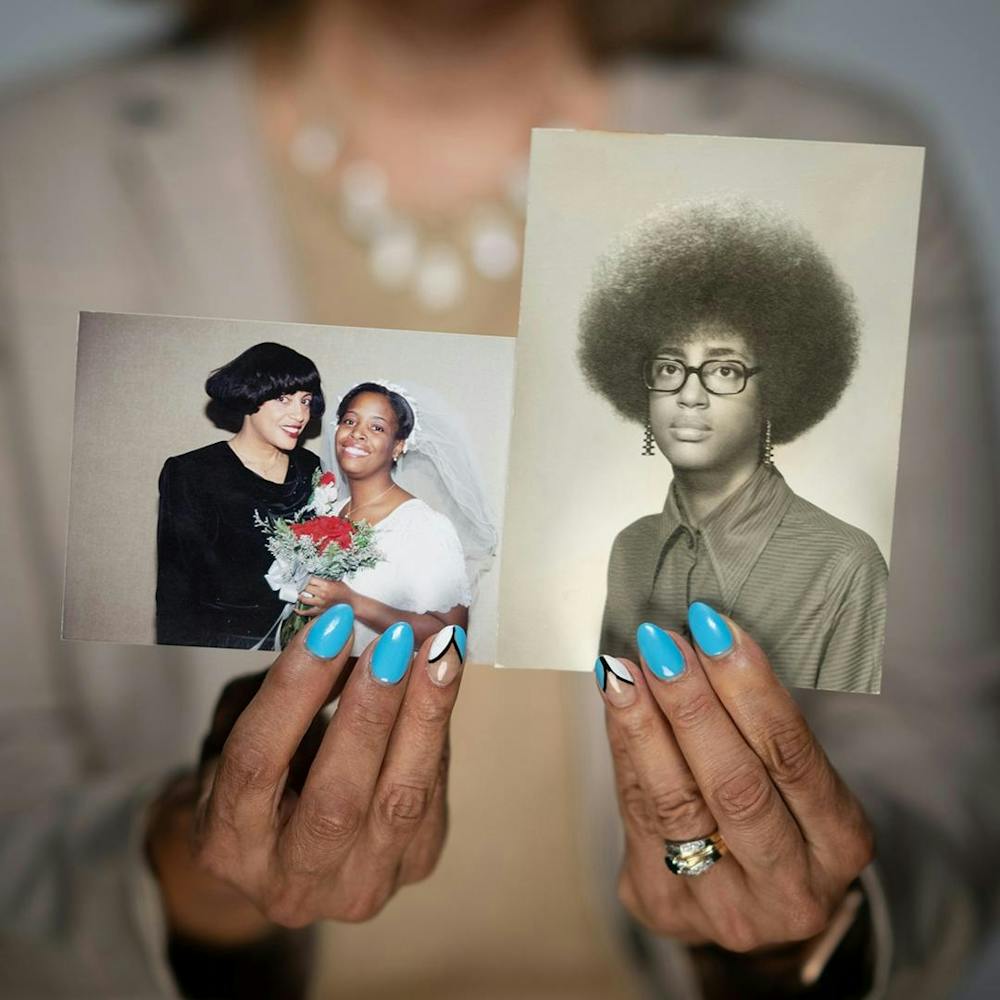

Linda Crear, 70

The first time Linda Crear asked her doctor for a birth control prescription, she was a young, married woman with a small child. The doctor, who had delivered her baby, agreed to write the prescription — if Crear got her husband’s permission first.

Crear and her husband eventually divorced. When she met someone else and got engaged, she wasn’t sure she wanted more children.

“So I went to that doctor for birth control pills, because that was the responsible thing to do. And I was told, ‘You’re not married, you don’t need birth control.’ In no uncertain terms. And now, it’s unconscionable, but back then you just took it,” Crear recalled. “I didn’t know who else to go to, there was no Internet, there was no resources, I didn’t have a mom at that point. And so I became pregnant.”

A Unitarian church in her Nebraska town connected Crear with a clinic in New York, and her fiancé agreed to pay for an abortion. It was her first time on an airplane.

“I never regretted that decision for a moment.”

Listen to Linda's story.0:54

Above, Crear with a photo of herself from around the time she got pregnant.

Kat Glessing, 73

After she got pregnant as a senior at the University of Minnesota, Kat Glessing borrowed $500 from a neighbor and traveled to Rapid City, S.D., where a doctor performed abortions illegally.

Glessing left a friend who’d traveled with her behind at the motel in case she got arrested at the clinic. She remembered being scared, and the clinking sound of medical instruments.

“After a period of time, it all ended,” she said. “And when he went into the other room to take care of the other woman, she apparently was further along than she knew. And so I’m on the table still with the sheet over me, and I can hear her screaming in the next room.”

Listen to Kat's story.0:45

Above, Glessing at an abortion rights rally with the doctor who more than a decade earlier had performed her abortion.

Martha Holton Dimick, 68

Martha Holton Dimick was a teenager living in Milwaukee in 1971 and preparing to go to college when she realized she was pregnant. Abortion was illegal in Wisconsin and neighboring Minnesota and she couldn’t afford to travel out of state. She’d heard horror stories about women who got unsafe back-alley abortions.

“My dad pulls me in the kitchen and they sit me down and my dad said, ‘You know, it’s really difficult raising a child, especially a Black child. What are your plans?” Dimick remembered. “And I said, ‘Well, what do you mean, what are my plans?’ I said, ‘My plan is, I’m going to have my baby.’”

She was pushed toward marriage with an abusive partner to raise her daughter. Dimick left her husband after he hit her, and she relied heavily on family to help with babysitting as she worked several jobs and went back to school. Dimick, now running for Hennepin County Attorney, said looking back on that time, she has no regrets about having her daughter. But she also felt she had few choices as a young Black woman.

“If you could afford to get an abortion, there was a way for you to do it, but most of the people that I knew at the time either had their babies or they gave them up. That was it.”

Listen to Martha's story.0:41

Above, Dimick with a photo of herself around the time she got pregnant, and one with her daughter on her wedding day.

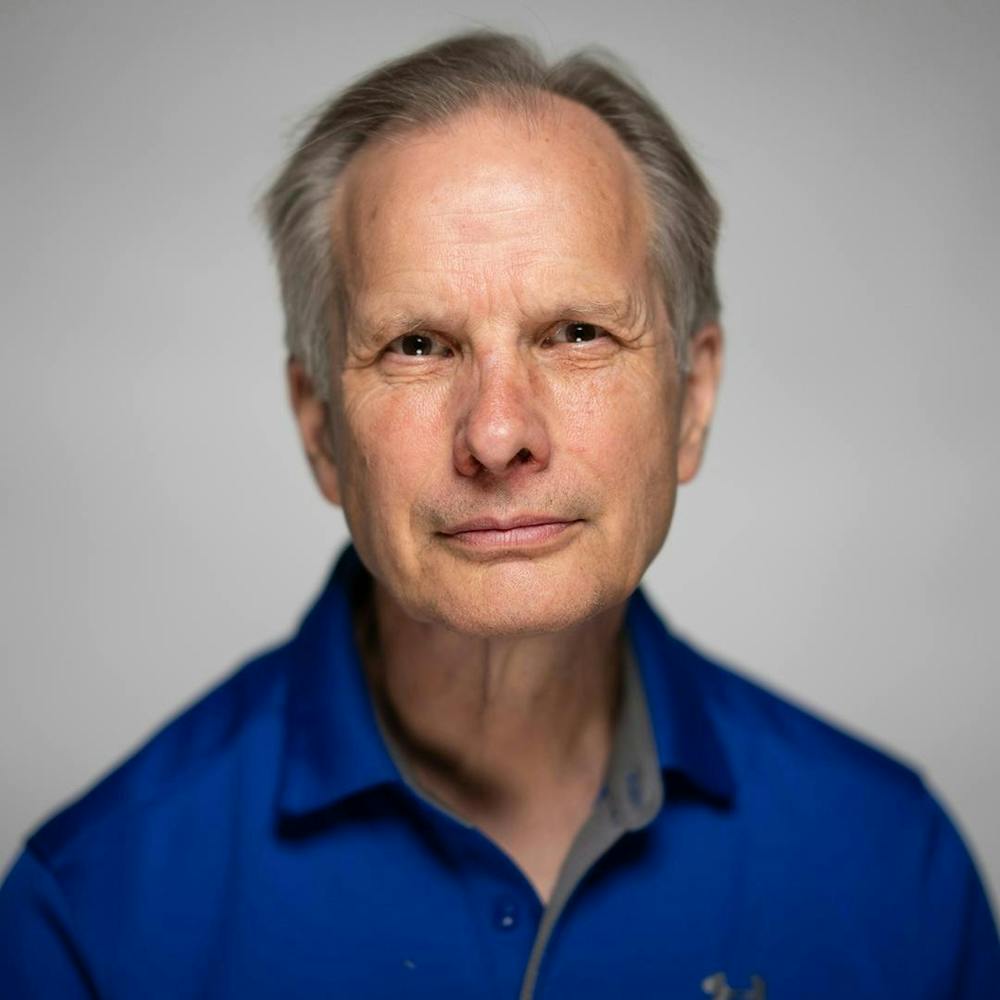

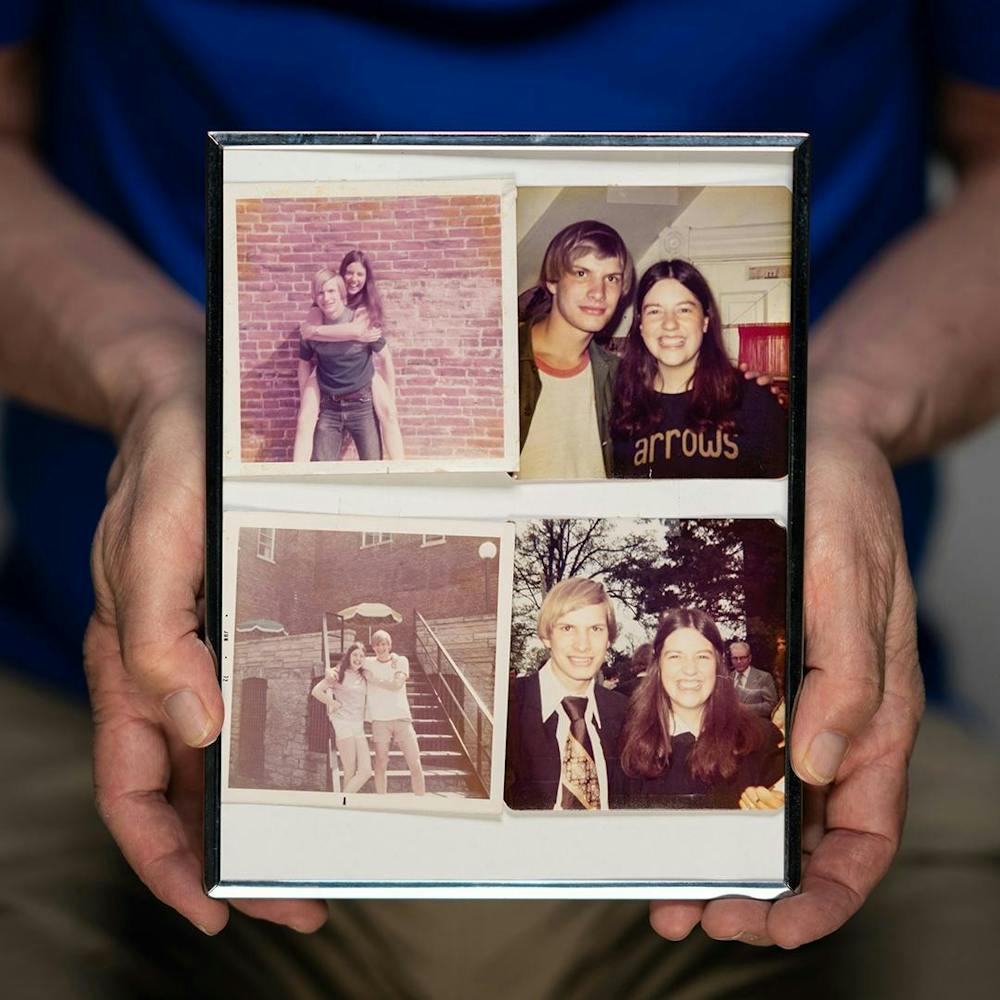

Jerry Gale, 70

In 1972, Jerry Gale was a sophomore in college and had been dating a woman named Nancy from Edina on and off again for nearly two years when she missed her period. She was pregnant, but they both knew they weren’t ready to start a family yet.

On April 20, which happened to be her birthday, Nancy flew to New York City to get a first-trimester abortion. Three years later, they got married and had a son and a daughter. “We never had any regrets about it,” Gale said. “We knew it was the right decision.”

Jerry and Nancy didn’t tell many people this story, but it wasn’t because they were ashamed. People just didn’t talk about these things. In 2017, Nancy died from colon cancer.

“There was this movement about let’s claim our abortion, let’s talk about our abortion. Out of that there was a need for men to be involved in the conversation. That’s a voice that is often missing.”

Listen to Jerry's story.0:47

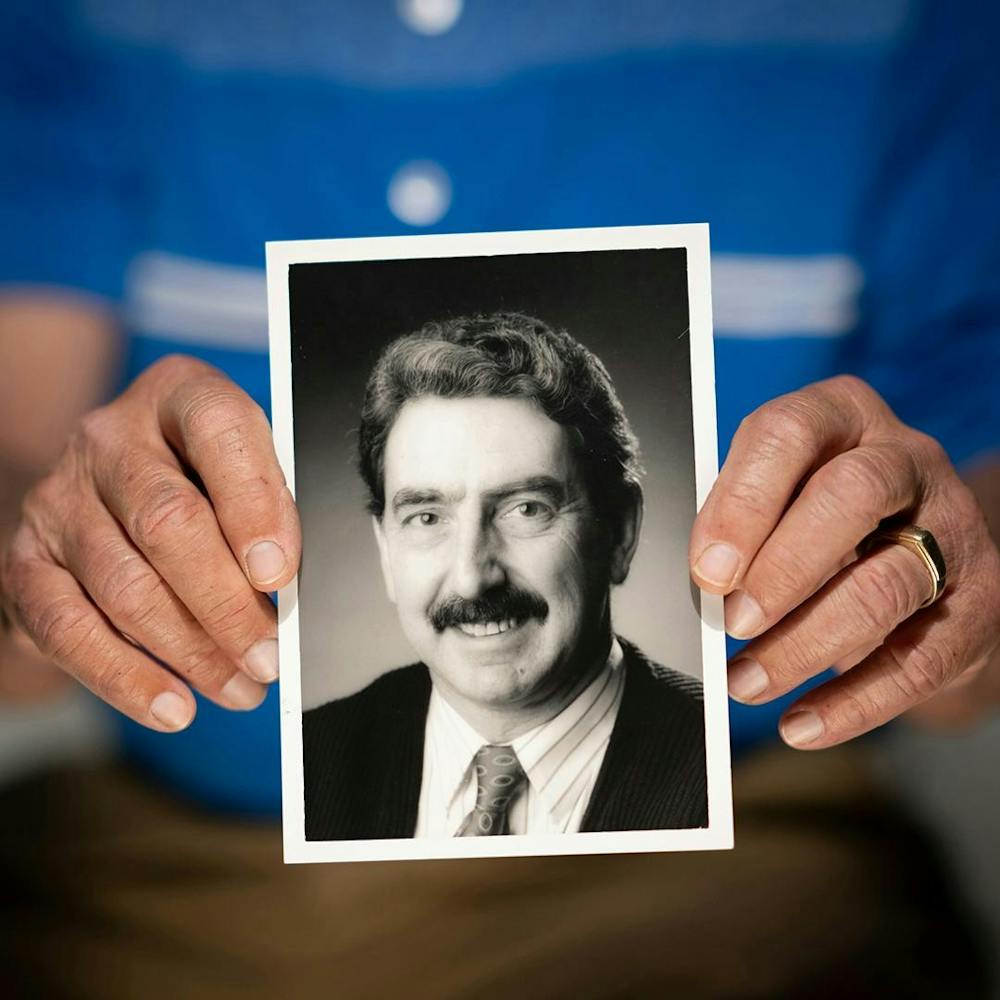

Above, Gale with photos of himself and his late wife around the time they got pregnant and chose to have an abortion.

Judy Finn, 70

Judy Finn’s family was already struggling when her mother became pregnant with a fifth child. Her father was working a second job, but there wasn’t always enough to eat, and shoes that wore out would be patched with cardboard.

A man showed up at their house on a Saturday and went into the bedroom with her mother. Finn, who was about 8 years old at the time, recalled that it seemed odd.

The next day, she was home alone with her mother.

“And she said, ‘Would you come here a minute?’ And I walked into the kitchen, and there are these huge blood clots all over the floor,” Finn recalled. “And I went in the bathroom, and she was sitting on the toilet. And the blood was just gushing out of her. And she said, ‘Clean up the floor, and then go get the neighbor on the other side of the alley, because she’s a nurse.’ Well, I started cleaning up the floor. And my mother said I got all pale like I was going to faint or something. So she said, ‘Just go get the nurse.’ So I went over there and told them.”

Finn’s mother survived, after being hospitalized and receiving blood transfusions. Finn didn’t learn until she was an adult that what she had seen that day was the result of an illegal abortion.

Listen to Judy's story.1:07

Above, Finn with a photo of her mother as a young woman.

Clare Gravon, 72

After Clare Gravon was sexually assaulted in 1968 at age 18, her mother and family doctor applied for her to get an abortion in Colorado — where the procedure was allowed under certain circumstances, including in cases of rape or incest.

A panel took up the application but ultimately denied it, citing the fact that Gravon was not from Colorado and the assault had not occurred there.

“I’ve never felt such gut-wrenching despair as I felt the day that we got that answer,” she said. “Later, a close friend told me that they had a connection that could help me get an illegal abortion, but even at 18, I knew that an illegal abortion was very dangerous, and that I might die. And as much as I wanted desperately to have an abortion, I wasn’t willing to die for one.”

Gravon went to live with her grandfather for a few months, and then to a home for unwed mothers in Duluth. She enrolled in classes at the University of Minnesota Duluth, and the baby was born over spring break — a traumatic birth following months of poor medical care and pregnancy complications. She placed the child for adoption and returned to school.

Listen to Clare's story.0:49

Above, Gravon with a photo of herself and her boyfriend at a dance right before she was assaulted by another man.

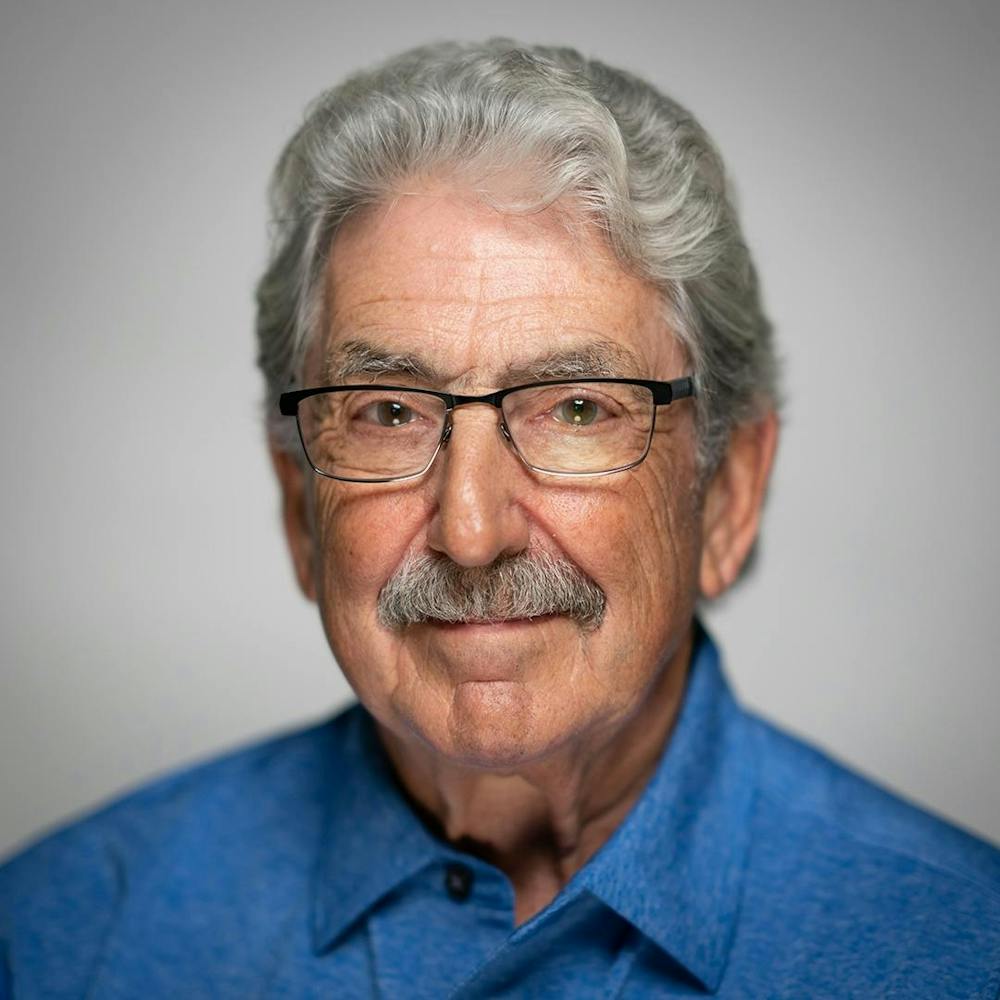

John O’Connell, 76

John O’Connell entered the University of Minnesota Medical School in 1968. Prior to Roe, he said, patients who suffered or died as the result of an illegal abortion were a common occurrence in the emergency room.

“[I] saw the results of the back alley, self-administered abortions — the infections and the problems that women would have,” he said. After the Roe decision came down, he said, “I saw those complications literally disappear.”

Listen to John's story.1:08

Above, O’Connell with a photo of himself from around the time he first saw a patient showing signs of an illegal abortion.

Mary Kunesh, 61

Mary Kunesh was 12 years old when the Roe decision came down, and remembers clearly the before and after — both what changed, and what didn’t.

“Really, a sense of relief for many, many women, because now they had a choice, where before their choices could be life-shattering no matter what they did,” said Kunesh.

But the world didn’t transform overnight, Kunesh recalled. Unmarried women who got pregnant still experienced stigma and shame. Growing up in a conservative Catholic family — Kunesh was one of 13 children — sex was a taboo topic. Her mother had told her daughters that if they became pregnant, there would be “a great estrangement.”

In 1978, at age 17, Kunesh was sexually assaulted by a classmate. She struggled to wrap her head around what had happened, much less what to do next. She confided in her oldest sister, who took her to Planned Parenthood in St. Paul. There, Kunesh learned that she had an ectopic pregnancy, in which a fertilized egg becomes trapped in the fallopian tube. The condition is fatal if left untreated.

Kunesh received medical treatment from a physician in Minneapolis. For decades, only her sister knew the full story.

“That’s just something that I’ve carried along with me through this time,” said Kunesh, now a state senator. “It just made me think about how many women or victims of violence never talk about it, through shame or not having processed the violence, and go to their graves with that burden on their hearts and their souls.”

Listen to Mary's story.0:55

Above, Kunesh with a photo of her late sister and confidant, Julie.

Credits

Reporting Emma Nelson, Briana Bierschbach

Photography and Videography Renee Jones Schneider

Editing Laura McCallum, Catherine Preus

Audience engagement Nancy Yang, Anna Ta

Design and development Anna Boone, Jamie Hutt, Josh Penrod