Desperate, then offered quick cash

They’ve suffered tragic, disabling injuries, and received large settlements to be paid over their lifetimes. Then little-regulated firms came calling.

The $12,001 payment Stanley Turner, 40, received from a California company in 2019 represented just 6.3% of the value of the $191,608 it was worth at the time.

The money was supposed to last the rest of Stanley Turner’s life.

He was 5 when a collision hurled him and his sister from the car, leaving both with permanent brain damage.

Doctors said Stanley would never live normally again.

The insurance company for the driver at fault in the crash settled the Turner family lawsuit by agreeing to a financial package worth more than $4 million to the children. The deal included guaranteed payments that would continue until Stanley turned 60.

He is only 40 now, but the checks have stopped coming. Instead, they’re being cashed by investors who persuaded judges in Minnesota and Florida to let them buy decades of Turner’s future payments.

For his latest sale in 2019 of more than half a million dollars in future payments, Turner received $12,001.

His mother, Barbara Turner, was still despondent a few months after the deal closed. She said her children would have had enough money to live even without working, but now they have almost nothing.

“The wolves have sucked it all out,” she said.

The Turners are among the 750,000 Americans who receive settlement payments, often guaranteed for life, after suffering catastrophic and permanent injuries. The money provides ongoing support to people whose lives have been shattered to the point that they often cannot earn an adequate income or provide for themselves or their families.

But the billions of dollars these victims receive each year also makes them targets for companies that operate in an obscure, largely unregulated niche of the financial services industry.

Each year, settlement purchasing companies persuade accident victims across the country to give up an estimated $1 billion in future payments in return for a much smaller lump sum of cash.

On average, the settlement purchasing companies keep about 60% of the money, according to a Star Tribune analysis of more than 2,400 deals from seven states between 2000 and 2020. In Minnesota alone, these companies have paid $28 million since 2010 for $70 million in future payments, court records show. At the time those deals were struck, the companies valued the payments at $53 million. Typically, payments are worth less the longer someone has to wait for them.

Gina Tedesco spent three years soliciting deals at a leading settlement purchaser. Photo by Saul Martinez • Special to the Star Tribune

Gina Tedesco, who spent three years soliciting deals at one of the industry leaders, said she believes settlement purchasers prey on people in desperate situations, even though some clients are “not in the right state of mind.”

“It just didn’t sit right,” said Tedesco, who earned $80,000 a year working for other companies before starting her own consulting firm that helped negotiate deals for sellers in 2017. “If you want to last, and survive, you have to not have a conscience.”

The pandemic damaged many sectors of the economy, but companies that buy future payments saw their business surge in Minnesota last year. Altogether, $8.1 million in settlement payments changed hands, close to a state record, documents show. Companies paid a total of $3.3 million for the right to those payments.

Companies signed deals with dozens of people who had never before sold their payments. Nearly a third of the sellers cited lost employment and other financial pressures from COVID-19 as a primary motivation, records show.

Court records show that many settlement recipients in Minnesota struggle with mental health problems or addiction, often as a result of a car crash. Among those who agreed to sell some or all of their settlement payments in Minnesota are 63 people who were ordered to obtain mental health services by a state judge. That list includes 27 people who were involuntarily committed to a mental institution at least once after engaging in bizarre or self-destructive behavior. Dozens of other customers were left cognitively impaired by lead paint poisoning or head injuries.

In some cases, records show, companies were allowed to buy payments just months after a person was released from mental health care facilities. Others were ordered to obtain mental health services shortly after the sale closed.

No state routinely requires the appointment of a guardian to protect the interests of a seller or their children, though judges in West Virginia must consult a guardian if the seller is an “infant, an incompetent person or a ward of the court.”

A sale may mean giving up years, even decades, of financial security — sometimes for pennies on the dollar. Records show that nearly 13% of people who sold their payments in Minnesota later filed for bankruptcy or were evicted from their homes.

Few federal or state laws govern these sales or limit the profits that investors can make. Only seven states, including Minnesota, require sellers to meet with an adviser, but that person is sometimes recommended by the company buying the payments, according to court records and interviews with sellers.

Advisers are not required to rule on the merits of the deal. Some are paid from the proceeds of the sale, which is illegal and has prompted a few judges to reject deals.

No state requires that a seller be represented by an attorney during court proceedings, and most were not in the cases reviewed by the Star Tribune.

New disclosure requirements adopted in 2014 by the Minnesota Legislature appear to be having little impact. Companies that buy the payments are paying, on average, about the same as they were before the rules went into effect, according to documents obtained by the Star Tribune.

County judges must sign off on every deal, but few say no. In the rare instances where Minnesota judges denied a deal, the Star Tribune found dozens of cases where payment buyers filed requests with a new judge, who approved the sale.

In interviews conducted over the past two years, a dozen judges complained about an approval process that seems stacked in favor of the settlement purchasing companies, with key information — such as civil commitment records — usually left out of files.

Some sellers were coached by the companies on how to handle challenging questions from a judge, interviews show. Judges who have denied deals have been removed from subsequent cases at the companies’ request, a maneuver that is legal in Minnesota and requires no supporting evidence.

Judge Kathryn Messerich

“I am horrified,” said Kathryn Messerich, chief judge of Dakota County. “This is one of those things that needs a legislative fix more than anything.”

Richard Cordray, who launched an investigation of the settlement purchasing industry when he was head of the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, said more oversight of payment purchasing firms is needed.

“A lot of tragedies occur when people become aware that other people have access to a substantial pot of money,” Cordray said. “There is always opportunity for predatory conduct, and they need to be policed more closely.”

Richard Cordray

Officials with the National Association of Settlement Purchasers, a trade group that represents some of the biggest buyers in the business, acknowledged that “bad actors” have engaged in questionable conduct. A spokesman said NASP is now trying to persuade lawmakers in all 50 states to adopt new rules that would make it harder to defraud settlement recipients. NASP also revised its code of ethics and standards of conduct after the Star Tribune presented its findings to the group.

“NASP and its members have taken extraordinary steps to protect consumers by implementing strict standards of conduct and leading efforts to enact robust laws in all 50 states and the District of Columbia,” NASP Executive Director Brian Dear said in a written response to questions.

Steve Matiatos of Lino Lakes was 7 when a 1,200-pound concrete sewer culvert rolled over him and partly crushed his skull. He lost most of his teeth and went blind in his right eye. His face was permanently scarred. He never finished high school.

Now 52, Matiatos could be receiving more than $2,000 a month from an out-of-court settlement that guaranteed him an income for life. But in 2000 he started selling his future payments to J.G. Wentworth, which buys more “structured settlements” than anyone else in the United States.

Wentworth went to court six times to buy payments from Matiatos. Twice, it had the judges assigned to his cases removed, court records show.

In one deal, Matiatos agreed to sell $90,000 of monthly payments he was scheduled to collect if he lived to age 59. Wentworth said those payments were worth about $75,000 under federal standards for valuing annuities, records from the 2015 case show. Matiatos received $20,000.

With the loss of sight in his remaining eye and unable to work, Matiatos will not receive another check until he is almost 80 years old. Altogether, Matiatos sold $1.5 million in payments to J.G. Wentworth for $226,500, about 25% of what the company said the payments were actually worth.

Unable to work, Steve Matiatos is supported by his family. He sold $1.5 million in payments for $226,500, about 25% of what the buyer said the payments were worth.

“I kick myself in the ass every day for doing this,” he said. “I’d be living like a king. Instead, I am probably going to be on the streets soon.”

Some sellers said they were incapable of understanding what they were doing at the time they agreed to sell their payments.

Sasha Stromberg spent two weeks in a coma after a car crash in 1984, when she was 6. She dropped out of high school in 10th grade and suffered a nervous breakdown at 27. Court records show she gave up three children for adoption “because of her inability to handle responsibilities.”

Since 2003, judges have allowed Peachtree Settlement Funding to buy $370,202 in payments from Stromberg for $77,202. The payments were valued at around $300,000. Stromberg said her ex-husband convinced her the deals would help them dig out of debt.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” Stromberg said. “It’s like they seen me coming.”

Wentworth, which merged with its biggest rival, Peachtree, in 2011, and other major settlement purchasing companies have declined repeated requests by the Star Tribune since 2019 to provide on-the-record comments about their business practices or specific cases. Wentworth’s chief executive and its top attorney traveled to the Twin Cities in late 2019 to meet with Star Tribune reporters and editors but ultimately declined an on-the-record interview. In a statement, the company said, “We are proud of our 25 year plus history of helping structured settlement holders access funds when they need it in transactions approved by judges.”

The former executive director of NASP said his members provide a valuable service to people whose circumstances or financial goals change. On its website, the group urges people to carefully read the disclosure statement that comes with each deal and reveals how much someone’s payments are currently worth and the amount of money sellers are giving up. Companies are required to provide those disclosures in Minnesota and other states.

“The vast majority of these people are working men and women who have had something go awry in their life, or they have an objective they want to achieve — whether it is buying a house, getting a car or sending a kid to college,” Earl Nesbitt, the trade group’s former leader, said in a 2019 interview. “This is simply an asset they are seeking to liquidate.”

The executive director of a group of large insurance companies and consultants who set up settlement packages said the Star Tribune’s findings about payment purchasers make his “skin crawl.”

“The way they prey on people is unconscionable,” said Eric Vaughn, executive director of the National Structured Settlements Trade Association. “I’m just angry.”

For the companies buying settlement payments, the deals usually carry little financial risk.

Structured settlement payouts are tax-free and guaranteed by some of the country’s biggest life insurance firms. Once sold, the payments go directly to the firm that bought them. Often, payments continue as scheduled even if the person who sold them dies before they are set to end.

In 2019, J.G. Wentworth sold $141 million worth of bonds backed by structured settlement payments it had purchased from individuals. Moody’s assigned the bonds its safest rating — the same given to bonds sold by the state of Minnesota. That AAA rating, Moody’s says, means such obligations “are judged to be of the highest quality, subject to the lowest level of credit risk.”

A small share of structured settlement payments are set to end when the victim dies. Records show that the companies buying this type of payment often require sellers to spend thousands of dollars on life insurance policies. If they die, the company is the beneficiary.

The Star Tribune examined more than 1,700 settlement sales filed in Minnesota since 2000 and found that judges approved 90% of the deals that went to a hearing. Reporters also reviewed more than 700 cases in other states.

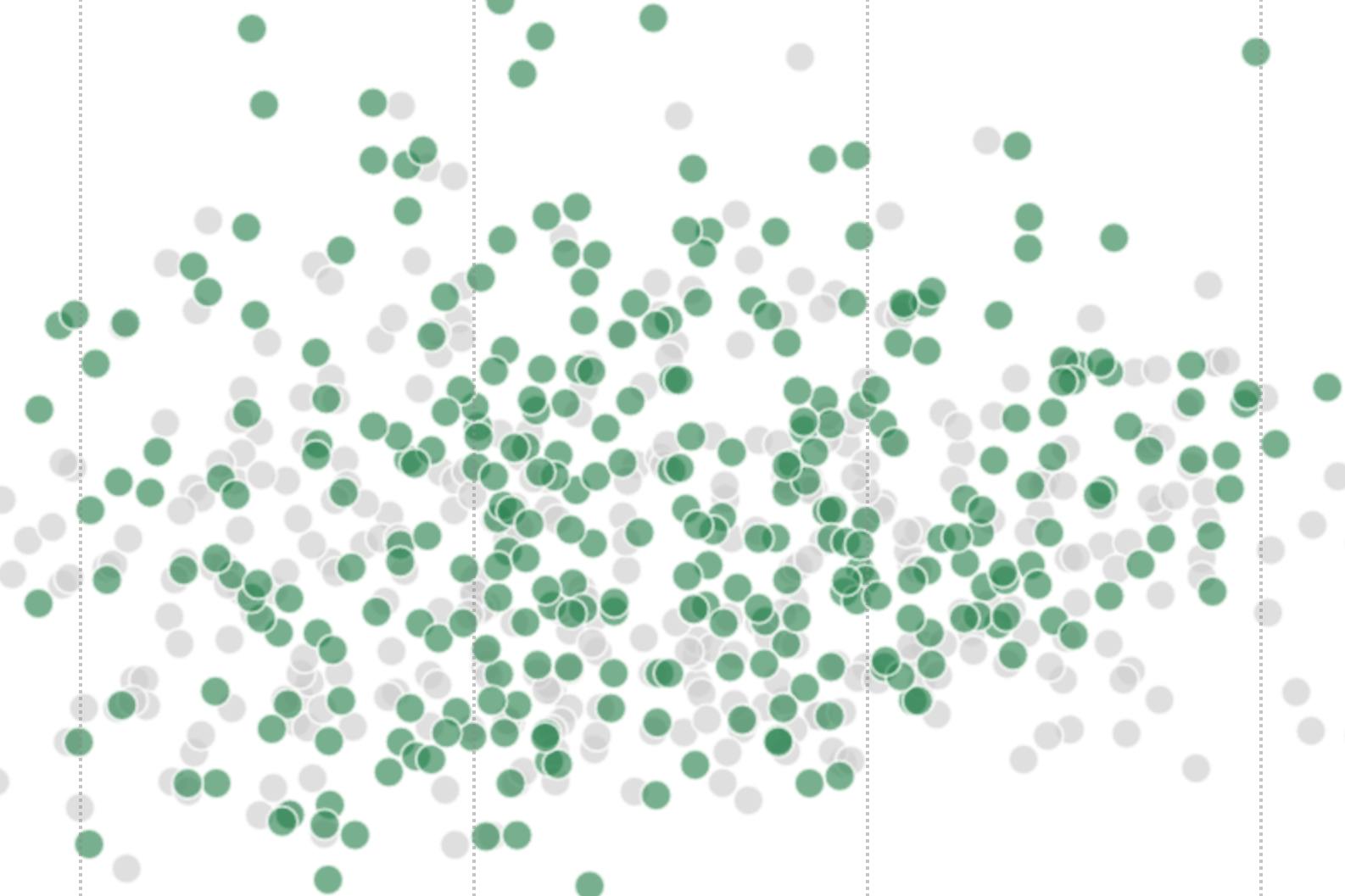

Millions in payments sold

For companies that buy settlement payments from accident victims, 2020 was one of the best years ever.

Source: Star Tribune analysis of Minnesota district court cases

In addition to reviewing case files, the Star Tribune attended 12 hearings and reviewed the transcripts of 64 more.

Most hearings in Minnesota end in less than 10 minutes, with judges rarely asking any probing questions.

The approval process is often casual. Though the sellers must typically appear in court, attorneys for the companies buying the payments are sometimes allowed to appear via speakerphone, records show.

Those rules were relaxed even more during the pandemic, when judges held video hearings via Zoom. Sellers usually testified from home, and judges sometimes had to remind them to take off baseball caps or move to quieter rooms when children’s noise interrupted the proceedings.

Some judges approve the deals reluctantly, even when they believe the seller may be making a mistake.

When Stanley Turner appeared in a Dakota County courtroom in 2019, it was the sixth time a firm had asked the courts to allow it to buy some of his payments. None of the previous requests were denied.

Turner has a lengthy rap sheet, including convictions for trespassing and domestic assault. A medical evaluation at age 14 concluded that Turner “underestimates the magnitude of his psychological and behavioral difficulties.” In 2019, Turner was sent to a St. Paul treatment center for drug abuse and mental problems after he was charged with assault and other crimes.

In a letter to one of the judges overseeing the cases, Turner pleaded for leniency, arguing that he has suffered from mental health problems since the car accident. He described himself as “crazy,” “disabled” and “institutionalized.”

“I am 40 years old and I have nothing to show for it,” said Turner, who was released from prison in May. “I’ve been homeless basically since I was 17.”

Turner wept as he reviewed his latest sale. He said he never learned how to manage money and doesn’t have a bank account. He said his mental problems often leave him “overwhelmed,” leading to bad decisions.

The most recent deal means Turner will not receive monthly settlement checks of $2,842 until he is 75. Court records show Turner’s future payments were worth $191,608 at the time of the transaction. The $12,001 payment he received in March 2019 from Catalina Structured Funding of California represented just 6.3% of the value.

“This stuff is heartbreaking; it’s so painful,” Turner said as he looked over the documents. “If I could only take some of this back.”

Dakota County Judge Tim Wermager warned Turner about the size of the discount he was taking at his hearing in 2019.

“I just don’t want you to second guess yourself because if it’s done today, it’s done today,” Wermager said, according to the transcript. “You are taking, in my mind, a small amount for what you’re giving up in the future.”

Wermager declined an interview request.

Turner, whose mental problems recently qualified him for state disability assistance, is now hoping to land a spot in an adult foster home. He said he bitterly regrets selling his monthly payments, claiming he was “manipulated” into the deal.

“I am not in a state mentally to make any kind of decisions,” he said. “I am not responsible at all. I try to stay out of trouble, but I am always getting locked away for doing something stupid.”

This was Catalina’s first deal with Turner. CEO Chris Milton said he has walked away from other deals with people with mental problems, and he blamed judges for any deals like Turner’s that slip through the cracks.

“I am not going to take advantage of someone who is not mentally competent,” Milton said.

Milton said Turner received so little money because the monthly payments he sold do not start until 2040, when Turner turns 60. Milton said his company made about $5,000 on the sale. Catalina was unable to obtain life insurance on Turner because of his medical conditions. His investors will earn hundreds of thousands of dollars if Turner lives long enough for 15 years of checks to roll in.

“It looks like I am making millions of dollars and ripping these people off — and that’s not the case,” Milton said.

Gary Davis, with visiting nurse Donna Sutton, received a total of about $744,000, or roughly 35 cents on the dollar, for payments valued at $1.7 million.

Gary Davis’ life changed forever in 2012 when a locomotive hit him while he was working in the rail yards in St. Cloud. A stroke a few days later destroyed at least 25% of his brain.

Gary Davis, who was hit by a train on the job, has sold more in structured settlement payments than anyone in Minnesota.

Davis now suffers from “compromised memory and does not have an ability to care for himself on a daily basis,” according to court records. His driver’s license was taken away. He walks with a cane and a nurse visits him regularly. Records show Davis also needs help paying his bills and tracking his personal finances.

Davis settled his lawsuit against the railroad for $2.5 million in 2014. He says his attorney at the time suggested he ask the court to appoint a conservator to help him manage the money.

Davis regrets that he never did.

A few weeks after receiving his settlement, Davis saw a commercial for J.G. Wentworth and called the company’s toll-free number. The company offered $100,000 in cash for $245,000 in monthly payments.

Davis, who said he wanted to pay down his mortgage and take his extended family on vacation, accepted.

Over the next three years, Minnesota judges allowed two companies to buy all of Davis’ remaining guaranteed payments. He sold more payments than anyone else in Minnesota, according to records obtained by the Star Tribune.

In return, Davis has received a total of $743,578, or roughly 35 cents on the dollar. The companies valued the payments at $1.7 million.

Davis used some of the cash to remodel his house and pay his bills, but he said he gave most of it away to friends and family members.

“I still don’t understand large sums of money,” Davis said. “To me, it is like the price of a candy bar or something.”

As he discussed his situation, Davis spoke haltingly, sometimes forgetting a question in the middle of answering it. In 2019, he learned that he forgot to pay about $8,000 in state taxes and owed $54,000, including interest and penalties. He agreed to repay the taxes to avoid losing his home.

“It makes me sick to my stomach,” Davis said. “I feel like I was taken advantage of.”

Until the 1960s, accident victims like Davis usually received one big check when their cases settled.

But a surge in personal injury litigation led to the adoption of what are known as structured settlements. Often these are set up as an annuity, with payments stretched out over time, in many cases for life. Sometimes, payments are scheduled to coincide with expected needs, like paying for ongoing medical treatment or covering living expenses for accident victims who cannot work.

In addition to being tax-free, scheduled payments proved popular for another reason: They reduced the likelihood that the money could be squandered quickly, which was a big problem in the past with cash awards.

“People blow through their cash settlements extremely quickly, but our money cannot be outlived,” said Vaughn, the head of the association of large insurance companies that fund structured settlements.

Around 1990, a few entrepreneurs figured out that there were significant numbers of people with long-running settlement packages who might be willing, even eager, to sell them for quick cash.

As the settlement purchasing industry grew, so did the number of horror stories.

Reacting to abuses, Congress passed a law in 2002 requiring all sales be approved by a local judge or face a big tax. But the rules that Minnesota and most other states have set for judges to follow are vague. No standards or formulas guide the process.

In most places, a judge can allow someone to sell their payments for virtually nothing, even if it is that person’s only reliable source of income, as long as they find the deal is in that person’s “best interest.”

A Hennepin County judge allowed 321 Henderson Receivables Origination to buy $80,100 in future payments for $14,000, even though they were valued by the company at $41,543. The seller, a 21-year-old man from Alexandria, Minn., could not finish high school because of the lingering effects of lead poisoning. He said he was evicted twice after selling his payments. In Cass County, a judge allowed Peachtree Settlement to buy $430,000 in guaranteed payments for about $85,000. The seller, a 29-year-old Bemidji man, had lost his leg at age 9. At the time of the deal, Peachtree valued the payments at $339,000.

For some, selling scheduled payments provides a needed jolt of cash to get ahead.

Texas resident Tyler Wade, who received a settlement over a day care injury he suffered at the age of 3, has sold $555,111 in payments to DRB Capital of Florida for $209,143. He said he used most of the money to buy a condo and pay down student debt.

“Would I do it again? Yes, if I ever needed that kind of money and I didn’t want to take out a loan,” said Wade, whose payments were valued at $417,792 by DRB at the time of the deals. “I feel like it was fair.”

Craig Ulman, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who helped draft the laws that govern settlement purchases in many states, said selling payments is rarely in the customer’s best interest.

“Many of their customers are vulnerable people,” Ulman said. “They are vulnerable by virtue of having sustained a disabling injury that in the worst case may have affected their judgment, their ability to appreciate the value of their settlement payments. … They need the protection that a structured settlement can afford.”

In 2016, both the Maryland attorney general and the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau accused a Maryland firm of reaping $17 million in profits from the sale of structured payments by victims of lead-paint poisoning and other incidents.

The court filings include the training manual Access Funding provided to its telephone salespeople. It describes the typical structured settlement recipient as someone who has “not adapted many of the necessary basic life skills that normal people must gain to survive in the world.”

The manual advises: “It is important to remember that [they] do not generally have the peace in their lives that comes with financial stability. Take this fact as a positive and take full advantage. You are their savior and the answer to all their problems.”

The cases are still pending.

No state requires that people selling their payments prove they are mentally competent.

In Minnesota, records show that one in eight transactions approved by local judges involved a seller with documented mental health problems. Many of those individuals received settlements after suffering traumatic brain injuries that permanently disrupted their lives.

Melanie Reynolds’ daughter broke her back and suffered a severe brain injury in a car accident when she was 4. She dropped out of high school in 10th grade and has “nonexistent” math skills.

“She cannot work,” Reynolds said in a 2019 interview. “Her disability income is gone as soon as she gets it. She will put it in some sort of video game or whatever before she deals with the actual bills.”

Her daughter, who could not be reached for comment, was involuntarily committed for mental illness seven times between 2006 and 2012. The following year, two Stearns County judges allowed Seneca One to buy $205,000 in future payments from her for $64,377. The company valued the payments at $182,502, court records show.

At one of the hearings, Reynolds’ daughter, then 26, told the judge she needed the money because she was unemployed and pregnant. In 2017 she was evicted from her Sartell apartment for nonpayment of rent, court records show.

“I don’t think she understands anything about what she was actually doing — nor does she understand the repercussions,” Reynolds said.

Nesbitt, the former head of the association that represents firms that buy structured settlements, said people should not be prevented from entering into such contracts “just because they have been involuntarily committed in the past or sought assistance for mental illness.”

“Almost every single one of them get back on their meds and lead productive lives,” Nesbitt said.

Tim Knaak was 17 when he received a six-figure settlement after the death of his father. Because he was born with a severe learning disability, Knaak had a court-appointed conservator to protect his assets until he turned 30 in 2008.

Seven years later he filed for bankruptcy in 2015 after selling $542,140 in payments for $132,922. At the time, the companies valued the payments at $465,523.

“They really took advantage of me,” said Knaak.

His first request to sell payments was denied by Wright County Judge Stephen Halsey, who noted that Knaak suffers from a mental handicap that “may prevent him from future employment other than manual labor.” He said Knaak showed no understanding of the financial implications of the deal.

But in subsequent years, two companies persuaded him to sell more of his payments. Halsey approved one of the deals, even though he noted in his order that “nothing has changed” for Knaak since his prior denial. Halsey declined to comment.

Knaak, who was supposed to get $1,183 a month for life, will not see another payment until he turns 65 in 2043. He said he used most of the money he got from the transactions to pay his bills. When he filed for bankruptcy, he had just $195 left in the bank.

“I didn’t understand it too well,” said Knaak, who works as a janitor. “I didn’t realize I lost all that money.”

Minnesota lawmakers tried several years ago to make it tougher for settlement purchasing companies to exploit people like Tasheeka Griffith, a victim of lead-paint poisoning as a child.

Griffith first tried to sell some of her payments after she turned 18. Hennepin County Judge Mel Dickstein, now retired, denied the sale because he believed the Minneapolis woman, a single mother, was still in high school and had trouble managing her finances.

Subsequent judges allowed Griffith to sell more than $350,000 in payments.

Three years later, she was back in Dickstein’s court trying to sell another $299,000 in payments for $19,000.

Dickstein was dismayed to learn that the money from the previous sales was spent. He was also troubled by the fact that she had not informed the judge of her previously approved deals.

“This case and the related cases are unfortunately poster children for why the transfer of structured settlement process may need repair,” Dickstein said at the 2011 hearing.

Spurred by Dickstein’s findings, the Minnesota Legislature passed new rules in 2014 requiring settlement purchasing companies to disclose prior attempts to buy an individual’s payments.

But the law included a big loophole: Companies are not required to disclose any prior deals involving their competitors. According to a Star Tribune review of 69 filings since the new rules went into effect, about half of the applications failed to include some or all of the prior requests.

Griffith, now 31, filed a total of 10 applications since 2008 to sell parts of her settlement. Four different judges allowed her to sell $732,828 in payments to three different companies for $137,214. The present value of those payments was not included in all of those transactions.

The deals have done little to improve her life. In 2011, Griffith told her attorney she was homeless, and in 2019 her infant daughter was placed into foster care and she was ordered to obtain individual psychotherapy after reports of child neglect.

Griffith did not respond to interview requests.

In 2019, Griffith filed a new request to sell another $761,277 in payments for $35,777 — about 10% of the present value disclosed in court records. It is one of the most one-sided deals ever filed in Minnesota.

The court filing did not disclose the three previous sales that judges had denied, or the deals Griffith had walked away from. Bruno Rodriguez, managing partner of Les Pitts LLC of Delaware, said he was unaware of the court denials or Griffith’s mental health problems before striking his deal with her.

“We don’t do a background check — we do a credit check,” Rodriguez said.

At her hearing in 2019, Griffith told Hennepin County Judge Daniel Moreno she wanted to do the deal because her living situation “is not OK for my children right now.”

When the judge pressed her on how much money she was giving up, Griffith defended the deal she had struck with Les Pitts. She said it was one of the few companies that did not try to “steal from me.”

“In the beginning, I was a vulnerable adult,” Griffith said at the hearing. “I wasn’t very understanding and aware of what I was doing, being honest. And they took advantage.”

Les Pitts eventually agreed to increase Griffith’s payment to $63,777 after arranging a $480,000 life insurance policy for her. Rodriguez said his investors will receive the money if Griffith dies before her payments end.

Moreno approved the sale. He declined to comment.

Rodriguez said the insurance policy allowed his company to pay Griffith three times as much as his competitors were offering.

“This industry is a difficult industry and there are a lot of players that do take advantage of unfortunate individuals,” Rodriguez said in a 2019 interview. “But we gave her more money than she’s ever gotten in any of her deals. She really got taken advantage of before.”

About the series

Unsettled is a Star Tribune special report examining how companies obtain court approval to purchase payments intended to help accident victims recover from their injuries. The series was largely reported in 2019 but publication was delayed when the pandemic struck in early 2020. Additional reporting was conducted in 2020 and 2021.

SERIES CREDITS

Reporting: Jeffrey Meitrodt, Nicole Norfleet and Adam Belz

Illustration: Brock Kaplan

Photos and videos: Jeff Wheeler, Mark Vancleave and Cheryl Diaz Meyer

Development: Thomas Oide

Design: Dave Braunger, Anna Boone, Josh Penrod

Graphics: C.J. Sinner

Editing: Eric Wieffering and Thom Kupper

Copy editing: Lisa Legge, Ginny Greene and Catherine Preus

Digital engagement: Anna Ta, Ashley Miller and Tom Horgen

ABOUT THE DATA

Applications to buy settlement payments are public record, and the Star Tribune reviewed more than 1,700 individual case filings in Minnesota courts over the last 20 years. We compiled a database with information on each case, including the company that bought the payments; the financial terms if available; the district court and presiding judge; whether the case was approved, denied, dismissed or pending, and notable details about the person filing to sell their settlement.

To measure individual outcomes, we filtered the data to about 1,200 sales that judges approved. We summarized those deals by person, identifying about 800 individuals who made at least one sale, including the total amount they sold and received. We removed people for whom we didn’t have financial details from all of their sales. This left nearly 700 people for whom we calculated the total percent of money they received against what they would have received had they not sold any payments.