RED WING, MINN. – The depth finder on Zach Paider's 23-foot tow boat on the Mississippi River tells the story of the struggle to keep sediment from choking Lake Pepin.

Over the dredged navigational channel where barges traverse, the readings can be 18 feet deep or more. Then, as the boat moves, the depth finder suddenly zooms to the low single digits, the screen's green graphic showing a steep hill under the murky water.

"We're going to go from 17 feet of water to 'Oh crap! My boat is stuck,' " Paider explained, pointing across a mile-wide watery expanse stretching to the Wisconsin shore. "It's shallow all the way across."

As the general manager of Bill's Bay Marina, Paider and other boat-rescue operators have been getting more calls the past few years to pull boats out of the muck. Farm runoff and erosion from the Minnesota River are blamed for an accelerated rate of sediment settling where the Mississippi widens to form one of the state's most popular recreational lakes.

With water depths sometimes reduced to less than a foot in some spots by midsummer, the Lake Pepin Legacy Alliance is taking action. The local grass-roots group is coordinating a public policy campaign with a long-term goal of slowing runoff and erosion upstream while advocating for a more immediate goal of strategic dredging and filling in new land in the lake's upper region to direct sediment into areas that will restore the local aquatic ecosystem — and make it safer for recreational boaters.

"If you can't control the amount coming in, you can control where it accumulates," said Rylee Main, the group's executive director. "The grounding problem could get worse if we can't make any changes."

Changing river

Sediment is always flowing and settling in the mighty Mississippi, but longtime residents near the head of Lake Pepin noticed it had accelerated in recent decades.

A Minnesota Pollution Control Agency analysis found in 2011 that sediment in Lake Pepin had increased tenfold in the past century, mostly from the Minnesota River.

A few local residents formed the alliance in 2009, concerned about the recreational and economic impact of the dramatic changes to the upper lake as well as the ecosystem.

With so much sediment clouding the water, including sands kicked up by winds and waves in shallow areas, less sunlight penetrates, leaving fewer aquatic plants to provide shelter and food for fish and wildlife. Shallow water also leaves less room for fish to survive when parts of the lake freeze in the winter.

Aerial photographs show mucky water swirling, especially, at the head of the lake near Red Wing and Bay City, Wis., Main said. In recent years, the lake has taken on up to a million metric tons of sediment per year, according to the Science Museum of Minnesota's St. Croix Watershed Research Station — enough to fill a full city block raised to the height of the Foshay Tower. It has both formed new land and raised the lake bottom.

New land

In Bay City, 71-year-old Jim Turvaville can see the changes when he looks out on the water from the property where he's lived since he was 5 years old.

"Ten years ago, that island wasn't there," he said, pointing to a spit of willow trees jutting into Lake Pepin in the distance. "There's all sandbars in there."

As village president for the community of 500 people, Turvaville said he sees activity at the local boat launch and campground drop dramatically once the water levels decline, cutting off motor boat access and hurting local businesses. He now sees half a dozen boats a year get stuck, he said, as his own two fishing boats rested on trailers behind him — the second one purchased because the first one is too big to use when the water is low.

In the shallow areas, boats are sometimes forced to speed up to plane atop the water's surface, creating dangerous situations when boat traffic is heavy and making for abrupt groundings, he said.

"People go roaring down through there and they don't know that sand bar in low water and they come to a sudden stop," Turvaville said.

The shallow water can catch even veteran boaters off guard.

Catfishing and sturgeon guide Brian Klawitter knows the hazards all too well. Though his 17-foot fishing boat will float in just 9 inches of water, he sometimes has to get out and push his customers out of a shallow spot, he said. On one trip last summer, his two customers had to get out and push, too. It was a 50-foot wading trek that they hadn't bargained for.

"They weren't prepared to get their socks wet," he said, adding that it was the first time in 13 years of guiding that he'd been stuck that badly.

Studying alternatives

The alliance, which says it is fighting for "ecological, social, and economic protection," now has more than 350 members. Main was hired as the group's first staff member in 2012. Just last year, the group hired an assistant director in an attempt to increase visibility locally and at state and federal offices upstream.

"A lot of people even living in the area, if they're not out on the water, they don't know it's filling in," Main said.

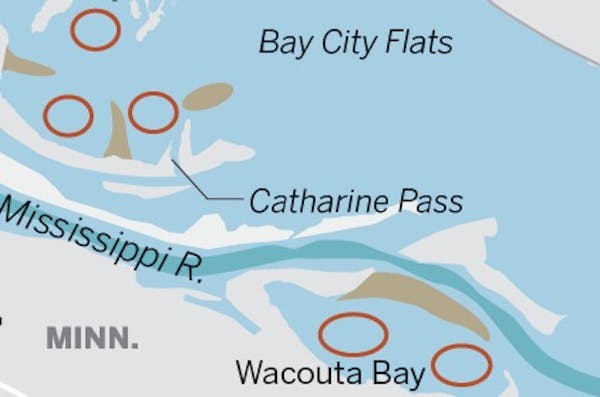

The group has been working with several state and local groups as well as some other nonprofits. The St. Paul office of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which maintains a 9-foot-deep navigational path for river commerce, is studying the feasibility of alternatives to dredge and fill in land around Wacouta Bay and Bay City. The new fill would create barriers for wind and sediment-depositing currents.

If approved by the regional Army Corps office, under the Water Resources Development Act, officials would be allowed to spend up to $10 million in federal money to use material dredged from the navigation channel, said Sierra Keenan, lead planner with the Corps in St. Paul. Additional material dredged from the bays could be used as topsoil for the new islands and peninsulas.

The plans would require a 35 percent state and local funding match.

The Wisconsin DNR would likely become the nonfederal sponsor, but "we don't have any kind of state funds that have been identified or targeted for this yet," said Jim Fischer, the DNR's Mississippi River team leader. The Legacy Alliance has made some commitments to help fundraise.

The groups are also vying to become part of a federal pilot project that could provide more money and allow dredging of the Bay City harbor and a navigation channel to it. Only 10 proposals will be selected nationwide, however.

Boaters confused

For now, tow boat operators are bracing for another busy season.

When the boats are too big or stuck too deep for Paider and other tows, Wayne Prokosch of River City Welding in Stockholm, Wis., typically gets called in.

Prokosch brings out a crane boat and often spends several hours — at a cost of thousands of dollars to the boater — to get big vessels freed.

Last year, he spent a couple of days dislodging a 3-ton boat, he said. In another case, he said, a boat captain suffered rib and lung injuries after he was thrown against his boat's steering wheel when hitting a sandbar at high speed.

Prokosch doesn't blame the boaters in a lot of cases, he said. The navigation channel is so narrow that barges often knock out the buoys marking it, confusing recreational boaters approaching from the center of the lake.

Increased sediment made the problem especially bad during low river levels the last couple of years, he said.

"Up until last year, we usually did three or four a year," Prokosch said. "But last year it was 22 or 23 boats … I never got a weekend off."

With shallow water levels promising to be an issue again this year, he said, he is gearing up for another busy season.

"The way it's going this year," he said, "I believe it's going to be as bad or worse."

Pam Louwagie • 612-673-7102