As anyone who's been cornered by a dullard at a party knows, one person's fascinations do not always prove interesting in the telling. Oliver Sacks, however, has a way of writing about his areas of lifelong interest — they include libraries, neurological disorders, botany and the history of science — that never fails to captivate me even if they are far from my own passions.

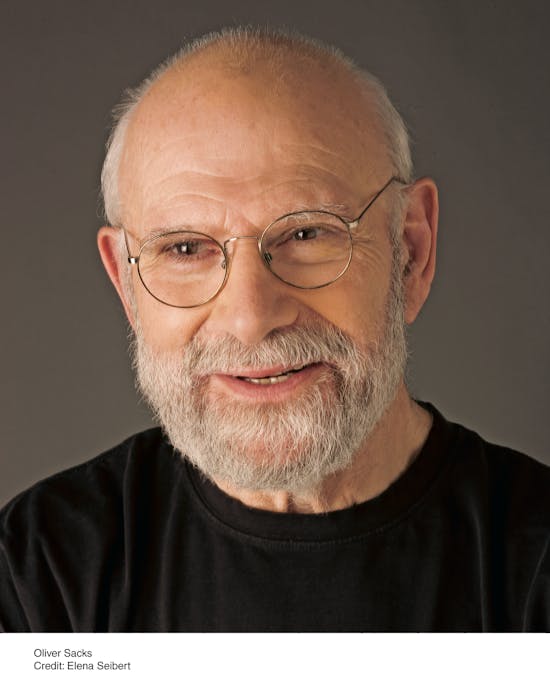

Sacks possesses the crucial knack of neither dumbing down nor writing over the head of a lay reader. A practicing physician and professor of neurology who died in 2015, he wrote a stack of well-received nonfiction books that fall in the category of science popularizers. The term diminishes their remarkable mash-up of scientific knowledge and the messier, more chaotic passions of life as we live it.

Much science writing for a general readership strains to explain specialized topics. For Sacks it's more about enthusing his way to promote appreciation (and greater understanding).

We get excited about, say, ferns because he is so into their beauty and resilience. Fossil records show how, when most of the world's plants and land animals were killed during a "great extinction" in the Cretaceous period, "life came bursting back in the form of ferns."

If you love fascinating tidbits, this book of uncollected or previously unpublished essays is for you. Who knew, for example, that hiccups have very little neurological explanation, but may be vestigial relations to the gill movements of our fishy ancestors? That a mature ginkgo tree has more than 100,000 leaves, and that they all fall at once each autumn? And then there's the brain-damaged writer who devises a way to read again by tracing words on the back of his teeth, using his tongue.

The essay "Cold Storage" could be lifted directly into an episode of the speculative-fiction TV series "Black Mirror." Sacks recounts the case of "Uncle Toby," a man who had been cared for at home by his family as he sank into an "icy stupor" that had lasted seven years when doctors discovered him. He was diagnosed with a severe thyroid malfunction. A thyroid hormone brought the man "back to life." Also revived by the treatment was a "highly malignant, rapidly proliferating oat-cell carcinoma" that killed him within just a few days.

Mortality, including Sacks' own impending death in his mid-80s, figures in several essays. "Life Continues" takes a dim view of changes wrought by the digital age, fearing that "what we are seeing — and bringing on ourselves — resembles a neurological catastrophe on a gigantic scale."

Sacks' tempers that pessimism with his own testament of faith. "Though I revere good writing and art and music, it seems to me that only science, aided by human decency, common sense, farsightedness, and concern for the unfortunate and the poor, offers the world any hope in its present morass." Which neatly summarizes the extraordinary career of a brilliant translator between far-apart worlds.

Claude Peck is a former Star Tribune editor and a member of the National Book Critics Circle.

Everything in Its Place

By: Oliver Sacks.

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf, 274 pages, $26.95.