Imagine trying to balance in the air a few feet off the ground while standing on a shaky, skinny nylon line stretched between a couple of trees in your backyard.

Just thinking about it probably makes you feel a little wobbly.

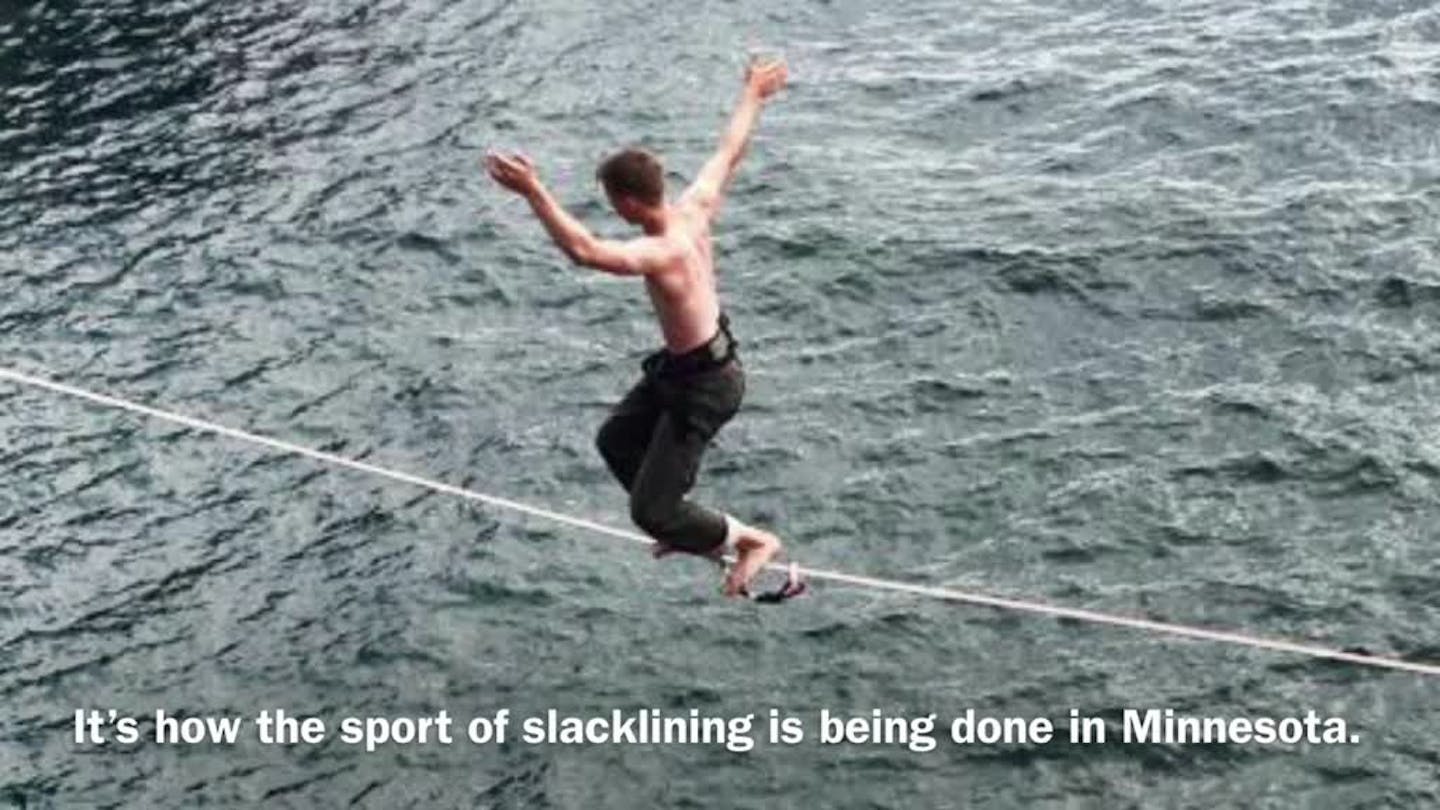

Now imagine if that line were two football fields long and suspended between two cliffs more than 100 feet above Lake Superior.

Mark McKee doesn't have to imagine. The 29-year-old Minneapolis man has done it. It's called slacklining, a niche sport that's getting its footing in the Twin Cities area and around the state.

"It's very scary at first," he said of being on a high slackline. "It's very nerve-racking. Your palms are sweating."

Slacklining resembles tightrope walking, except that instead of walking on a rigid, tensioned high wire, you're trying to balance on a length of flat nylon webbing an inch or two wide. And that webbing has stretch and bounce.

Unlike tightrope walkers, slackliners don't use a pole for balance. But on high slacklines, they do wear a climbing harness and a safety leash to catch them if they fall.

The sport was pioneered about 40 years ago by rock climbers largely in the West. They stretched webbing lines between trees in the campgrounds at Yosemite National Park as a way to challenge themselves when they weren't climbing.

Over time, the activity has become more mainstream with affordable starter slackline kits that are easy for anyone to set up and try in the backyard.

It's also become more extreme, with vertiginous slacklining stunts attempted between tall buildings, using hot air balloons or crossing mountain gorges using lines hundreds of feet long, thousands of feet above the ground.

Nothing quite that intense has been attempted in Minnesota, but local slackliners are doing their best to push the envelope.

"In Minnesota, the geography presents its limitations, but we're working on it," said McKee, the organizer of a Facebook group called MINNSLACK.

This summer, a small group of slackliners has been rigging a line above Lake Superior between the cliffs at Palisade Head at Tettegouche State Park on the North Shore.

The anchor points are about 180 feet high and the line stretches about 585 feet across the water. Local slackliners believe it is the longest high slackline attempted in the state.

"The key words are longer and higher," said McKee, who someday would like to rig a slackline on the Mississippi River bluffs in the Twin Cities and walk above the river from bank to bank.

McKee, who has also lived in Utah and has slacklined around the country, is a masonry contractor who started slacklining in 2010.

When he moved back to Minnesota in 2013, he started MINNSLACK to foster interest in the sport and arrange outings. The group has about 300 members. McKee also started a podcast about slacklining in North America (minnslack.com/webslackline).

At a park near you

Much of what MINNSLACK does is less extreme than defying gravity above Lake Superior. They usually meet a couple of times a week to slackline between trees in local parks or around the Chain of Lakes in Minneapolis.

A favorite spot is off Theodore Wirth Parkway in north Minneapolis in an open park field with a bowl-shaped depression that's too hilly for soccer and doesn't get much foot traffic. The lines they rig there aren't very high, but can be up to 750 feet long.

While neither the Minneapolis Park Board nor the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources prohibits slacklining, guidelines may be developed if the activity becomes more widespread.

McKee said MINNSLACK members are aware that they're on public property.

"It's an unfamiliar thing for folks," he said. "We do our best to be good stewards of the activity and do our best to answer questions." And, of course, to encourage others to join the group.

The common first reaction for people who try it: "I'll never be able to do this." But McKee insists that almost anyone can walk on a slackline. The main requirement is persistence.

"Your greatest barrier to success on a line is your mental state," he said.

For the first couple of years, McKee said, he practiced on lines 2 to 5 feet off the ground. It took him an hour every day for two weeks before he could walk 30 feet.

"Once you're familiar with a given slackline, the ability to walk across it without falling is 95 percent mental," McKee said.

Enthusiasts compare slacklining to everything from meditation to flying.

An 'escape'

"It lets you kind of escape from everything else because it requires that deep meditative focus," said Hunter Cottrell, a college student and slackliner from Forest Lake.

"I like the feeling of being in the air," said Meridith Graham, a 26-year-old St. Paul woman who likes to do "tricklining," which is bouncing on a slackline like a sort of skinny trampoline.

Typically done in bare feet, Minnesota slackliners continue their sport in the winter using neoprene footwear. McKee said that his group would like to find practice space indoors and that they're always looking for interesting new outdoor locations.

"Any two elevated points 100 to about 2,500 feet apart are of interest to us," he said.

Slacklining high above the ground is called highlining, and it's not for beginners, McKee said. To safely set up the lines, slackliners use specialized equipment and rigging procedures similar to those used by rock climbers and in industrial rigging. McKee said the Palisade Head line took about four hours to set up, and is designed with redundant safety features.

A highline actually consists of two lines, separately anchored. A person walking on the line has to wear a climbing harness tied to a 4-foot-long leash with double lines. The leash is connected to the slackline so that in case of a fall, the slackliner will drop only a few feet before being caught. The lines are capable of holding at least four times the load they are expected to experience.

The leash is connected to the slackline with a drop forged steel ring that slides along the line and is capable of supporting at least 10,000 pounds before breaking. Folks actually use two of the rings at the same time to be doubly sure.

Extreme but safe?

Despite how dangerous it looks, there have been only a handful of slackline-related fatalities, according to a 2016 report from the International Slackline Association. The group said the only highlining death occurred in 2011 in Slovenia and was caused by inappropriate use of equipment.

Done correctly, highlining is "the safest 'extreme sport' you'll find," McKee said.

Safe perhaps, but not necessarily easy.

McKee said this summer he and another slackliner, Michael Nichols, each got across the 585-foot line at Palisade Head with just one fall.

"If everything is gravy, you can stroll right across," McKee said.

Other times, he has spent a frustrating hour on the line, falling 30 or 40 times, having to climb back on the line each time before finally getting across.

He said so far no slackliner has crossed the Palisade span without falling at least once. Members of his group hope to try it again in October.

"You kind of feel like you're in the middle of nowhere," Cottrell said of the high slackline above Lake Superior.

"It's kind of enjoyable because no one's ever been there before."