LUVERNE, Minn.

When the new water pipe finally arrived, this tiny prairie town overnight became a perfect place to grow shrimp.

In southwestern Minnesota there's food for them — corn, soybeans and wheat. There's plenty of land, plus know-how and an entrepreneurial spirit from local companies.

And now, after a quarter-century of struggle to build the Lewis & Clark Regional Water System, there's enough water for this landlocked spot to produce 7.5 million pounds of shrimp a year. It also means there's water for a cheese factory in Iowa, for rapidly expanding businesses in Sioux Falls, and for a community splash pad in Worthington, where water for playing was often a luxury.

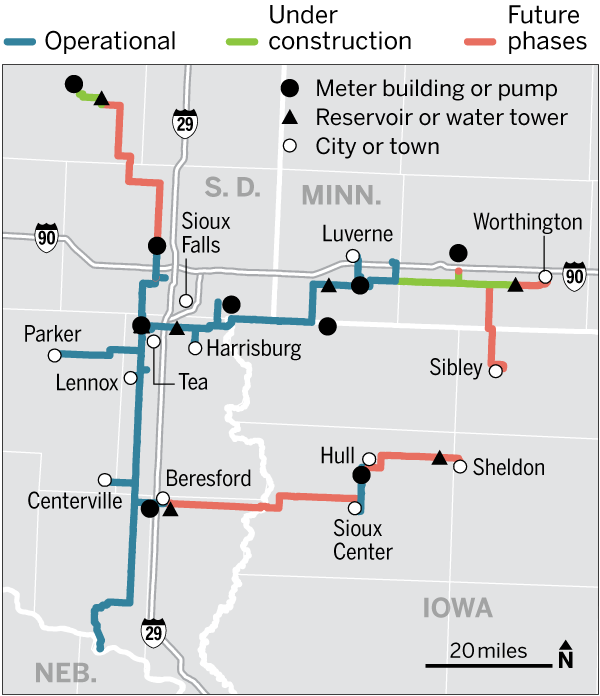

The Lewis & Clark system — 337 miles of underground pipes connecting 20 towns and utilities in three states — was once a literal pipe dream. But today it is viewed by many as an ambitious and prescient solution to the water shortages and contamination that have constrained southwestern Minnesota for decades, and that could soon affect other Midwestern communities as well.

The project required unusual cooperation among community leaders from Sioux Falls to Worthington, as well as nearly $590 million in state and federal subsidies. It also relies on the force of South Dakota water laws, which treat water as a precious resource that must be preserved and protected.

Mainly, it got built because a handful of community leaders recognized that "water is the new oil," and the way to get it was to band together, said Troy Larson, the water system's executive director.

"You can't create more water," he said. "But in the Midwest, we take it for granted."

That's not been true, however, in Worthington, Luverne and other southwest Minnesota towns. This part of the state gets about the same amount of precipitation as the rest of the southern half of the state, but it was cursed by glaciers that receded 10,000 years ago. They left behind only shallow deposits to collect groundwater, creating limited supplies that are vulnerable to drought and subject to contamination from decades of farm fertilizers used on porous soils.

"Worthington has struggled throughout its history with adequate water supplies," said Scott Hain, the city's director of public utilities.

Now, he said, he's watching with some sympathy as other Midwestern communities confront similar challenges. Irrigation is straining aquifers that feed the Mississippi River in the center of Minnesota. Cities across the state's farming regions are spending millions to remove agricultural contaminants from drinking water. And east metro communities are struggling to protect their beloved White Bear Lake from the effects of groundwater pumping.

"All of a sudden, the chickens are coming home to roost all over the state," Hain said.

Aaron Lavinsky

'We were trailblazers'

In Worthington, economic development officials learned long ago that the first question they have to ask prospective businesses is, "How much water do you need?" Hain said. "Worthington would have been a larger community had water never been a concern."

Luverne has similar problems, and its groundwater is naturally contaminated with iron and manganese that is expensive to remove. As a result, the city operates 18 municipal wells in order to provide enough water for a population of 4,700. It has turned away water-intensive ag businesses like cheese and dairy plants. Even local farmers couldn't expand their livestock operations because of limits on supply, said Mayor Pat Baustian.

And during droughts it came perilously close to pumping the aquifers dry, he said.

"We were sweating it on our wells," he said.

The idea behind Lewis & Clark was rooted in forecasts 30 years ago that southeastern South Dakota would eventually run out of water for growth, especially the rapidly expanding city of Sioux Falls. In fact, the city did max out on its water supply in 2012, just before it connected to the Lewis & Clark.

The solution was simple but ambitious: Draw water from an aquifer fed by the Missouri River along the southern border of South Dakota and then pump it to 20 towns and utilities in three states that together own and manage it as a nonprofit. It will eventually pump up to 45 million gallons daily — almost enough for a city the size of Minneapolis.

Twenty-five years ago the Lewis & Clark was a huge gamble for the communities that were offered the one-time chance to sign on. It would need city, state and federal funding. It required upfront money for a pipe that wouldn't deliver water for a decade or more for future businesses that might never materialize.

For many, the risks were too great. Over time, the 40 towns and small water systems in South Dakota, Iowa and Minnesota that initially expressed interest dwindled to 20.

Worthington, Hain said, didn't hesitate. But, he added, "we were trailblazers."

Now, those cities are starting to reap the rewards.

When Baustian sat down with executives from tru Shrimp in 2016 to pitch Luverne as the site for their shrimp production plant, his first question was a natural.

"Have you ever heard of the Lewis & Clark?" he asked.

They had not.

The company is a private startup launched by the owners of Ralco, a Marshall, Minn., feed and nutrition company that is turning the traditional livestock business on its head.

"We have changed the rules on how to grow shrimp," said general manager Mike Ziebell.

Using patented tank technology, the company wants to provide a new source of disease-free, nonpolluting shrimp for the global market, raised in the middle of the prairie 800 miles away from the ocean.

The prototype is housed inside a giant concrete box attached to the side of the former elementary school in the tiny town of Balaton, Minn., near Luverne.

Balaton Bay Reef, they call it.

Shrimp hatchery tanks fill what used to be classrooms, and a stack of 150-foot-long plastic-shrouded tanks rise 42 feet high inside the dim, cavernous space of the new concrete addition. Shrimp, it turns out, grow better in the dark.

When the production facility opens in 2020, it will create more than 100 jobs and have enough tanks and a hatchery facility to produce more than 7 million pounds of whole shrimp annually. For that, the company needs water — 14 million gallons at the start of production for even bigger tanks, and 300,000 gallons per day after that.

But it's already generating revenue for Luverne. More than 30 employees from places like Hawaii, India and the fisheries division of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources are spending some of their paychecks in town.

Earlier this month, the kitchen staff at Benson's, the tiny cafe in the back of the Clark gas station in Balaton, got the job of cleaning and cooking 1,500 locally grown shrimp for the company's Christmas party.

"It's been a huge boost for our local economy," said cafe owner Mike Benson.

For the first time in its history, Baustian was able to tell a company that Luverne "has treated, softened water at the city gate." Now, the fire hydrants and sewer lines are in place, and next year tru Shrimp expects to start construction on 68 acres along I-90 on the west side of town.

"It is by far the biggest example we've had of the mantra, build it and they will come," said Larson of Lewis & Clark. "We just couldn't prove that in advance."

Aaron Lavinsky

Minnesota ponies up

Lewis & Clark relies on a feature of water law that doesn't exist in many water-rich states, including Minnesota. In drier states like South Dakota, water managers are forced to look ahead in order to manage tight supplies. That's helped generate a legal system that allows large users — irrigators, industry and cities — to plan ahead as well by staking a claim on water supplies that they won't need until later.

But South Dakota takes it a step further with statutes that also outlaw the depletion of water sources. The state can't promise more water than nature will replace, an amount determined by long-term monitoring. "It does recognize that water is a limited resource," said Ron Duvall, an administrator with the state's Water Rights Program.

In addition, Lewis & Clark's creators thought big. In contrast to the many rural water systems that supply pockets of farmers and small towns, including some in western Minnesota, Lewis & Clark serves cities and other water systems. It's a nonprofit, nongovernmental entity owned by its members across a geographical region that includes parts of three states.

"The whole concept was to pool financial and political resources … rather than everyone doing their own thing," said Larson.

But paying for it was an uphill fight. At one point, when the system's construction stalled at the Minnesota border, some dubbed it "the pipe to nowhere."

"When you have abundant water, you don't think this is a big deal," said Luverne's Mayor Baustian, describing the reaction of state and federal representatives during annual lobbying trips to St. Paul and Washington, D.C. "But it is a big deal."

To date, the federal government has not come through with all its share. Though Congress authorized the funding, it's paid only about half its promised share for construction. Instead, the three states have paid their own commitments — and that of the federal government's — in the form of zero interest loans to Lewis & Clark.

Legislators in Minnesota, where bipartisan political support for the project grew over time, have been the most generous of all. In addition to its own share, $5.45 million, under Gov. Mark Dayton the state has advanced $39.5 million of the nearly $188 million that the federal government owes.

Some point out that it's all been an extraordinary leap of faith for Iowa and Minnesota. After all, it's still South Dakota's water. David Ganje, a natural resources attorney in Rapid City, said he wonders what could happen if South Dakota suddenly decides it needs the water for its own citizens since there is no compact between the states on how to manage a shortage.

Two aquifers in South Dakota are already maxed out by users, he said, and the state often issues shut-off orders to water systems during dry periods. What it shows, he said, is complacency in the face of continued economic growth, climate change and a future in which water issues will only get bigger and more complicated.

"This is going to be a problem when there is a water shortage or natural disaster or production facility breakdown," he said. "And usually the end user is screaming bloody murder."

Aaron Lavinsky

Larson disagreed. Short of an "apocalyptic situation," South Dakota's bedrock water laws are enough, he said.

"The water right is Lewis & Clark's," he said.

The system's success faces other challenges. While it has strong laws related to supply, South Dakota is much less rigorous in protecting lakes and streams from urban and agricultural pollution. And the permits that govern discharges from many water treatment plants are long out of date. Now, some sources that draw from lakes and rivers are becoming polluted as well.

How, or even if, to protect them is not getting much reception from state leaders, said Jay Gilbertson, manager of the East Dakota Water Development District.

For now, though, Luverne, Worthington and other co-members are promised enough clean water to grow for the next 40 to 50 years. If it's not enough, the system has room for expansion, and future water rights, for up to 60 million gallons a day.

But it's all spoken for. Today, the system's huge pipes bypass cities that decades ago said no thanks — a decision that has come back to haunt some.

Brandon, a suburb of Sioux Falls, has seen its population double; it's now struggling with both a shortage of water and quality problems from naturally occurring radium in its system. Former City Administrator Dennis Olson said he has no regrets about turning down Lewis & Clark nearly two decades ago. At the time, it was expensive, he said.

"And eventually we would run out and we would still have a problem," he said.

But this year the lawn watering bans and health worries in Brandon erupted into political battles that helped spur a near complete turnover of the City Council. Resident Tim Wakefield Jr. even went so far as to ask Lewis & Clark officials whether it was too late for Brandon to connect.

It is.

But after running unopposed on water issues, Wakefield is now one of the new members on the City Council.

"Water really is the lifeblood of a community," he said. "It sets the tone."