Star Tribune

Extreme isolation scars state inmates

Minnesota prisons pile on solitary confinement, often for minor offenses, causing lasting mental problems for inmates. Other states are scaling back.

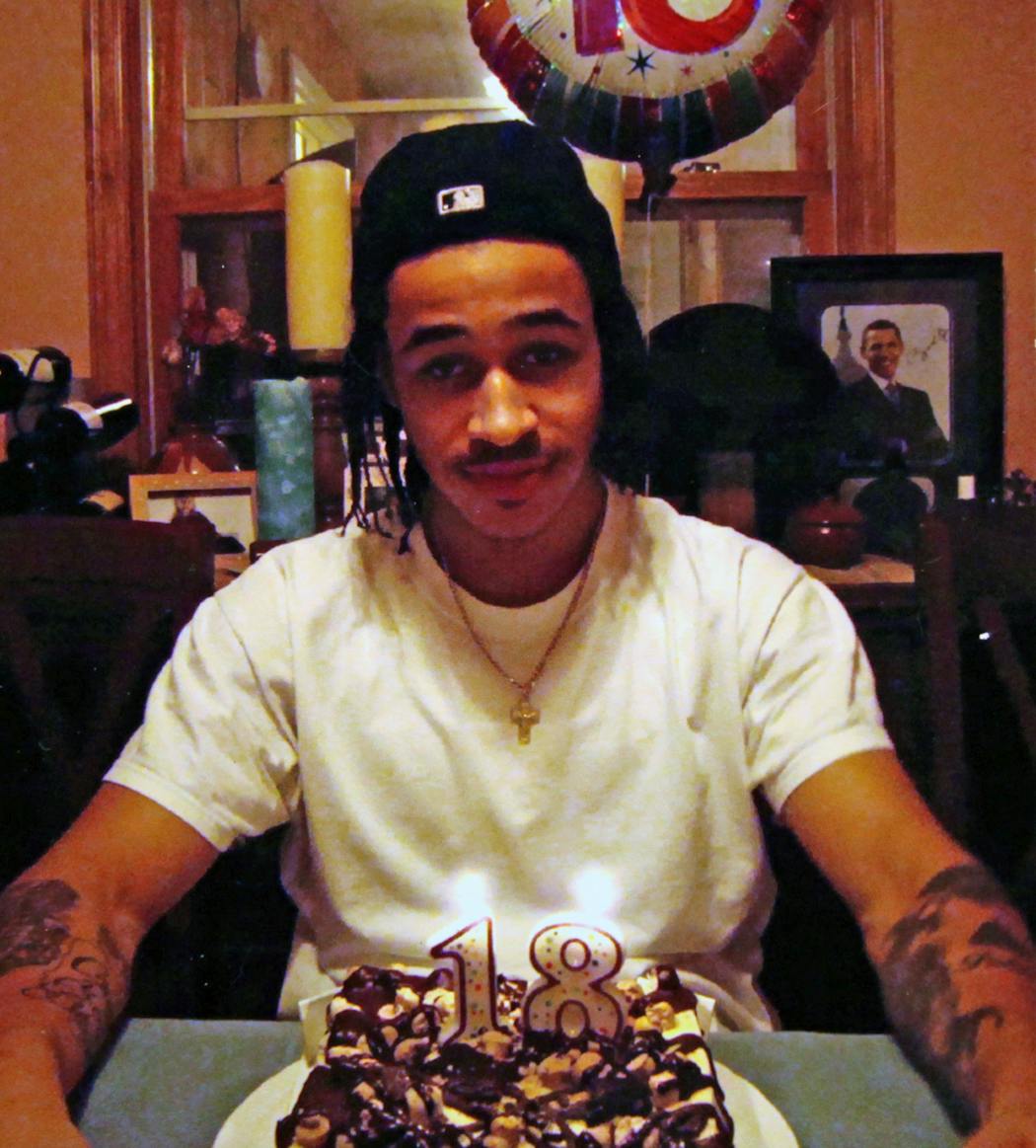

Anthony Nasseff lay awake for hours silent, staring at the metal slot on his prison cell door, waiting for his breakfast tray to appear. That signaled morning: the beginning of another day of tedium, despair and loneliness. Nasseff was a 20-year-old inmate at Minnesota's Oak Park Heights prison when a disorderly conduct citation earned him an initially short stay in solitary confinement.

It lasted three years.

For at least 23 hours a day, walled off from all outside sounds, Nasseff was confined inside an 8 ½-by-11-foot cell. A single bed, concrete bench, shower and toilet left just enough space for him to do push-ups. A camera mounted on the ceiling watched him at all times. Unseen hands flushed the toilet and controlled the light.

Overwhelmed by constant solitude, Nasseff decided to end his life. First he tried to choke himself to death with a bedsheet. Later he attempted overdosing on over-the-counter pain medication. When that didn't work, he stopped eating and drinking, hoping his body would stop functioning. He calculated five days would be long enough. But he broke down after three and accepted water.

"I couldn't take the isolation," he said. "I couldn't take being alone, being stuck in a cell with nothing to do, no one to talk to, no one to really connect with. I spent so many years alone."

Nasseff was in every physical sense isolated, but his story is common in Minnesota's state prisons.

He is one of thousands of inmates across the state punished with solitary confinement — which inmates call "seg," for segregation, or the "hole" — for long periods of time, frequently for just minor infractions, and often with no regard for their mental illnesses, an examination of state Department of Corrections records from the past decade shows.

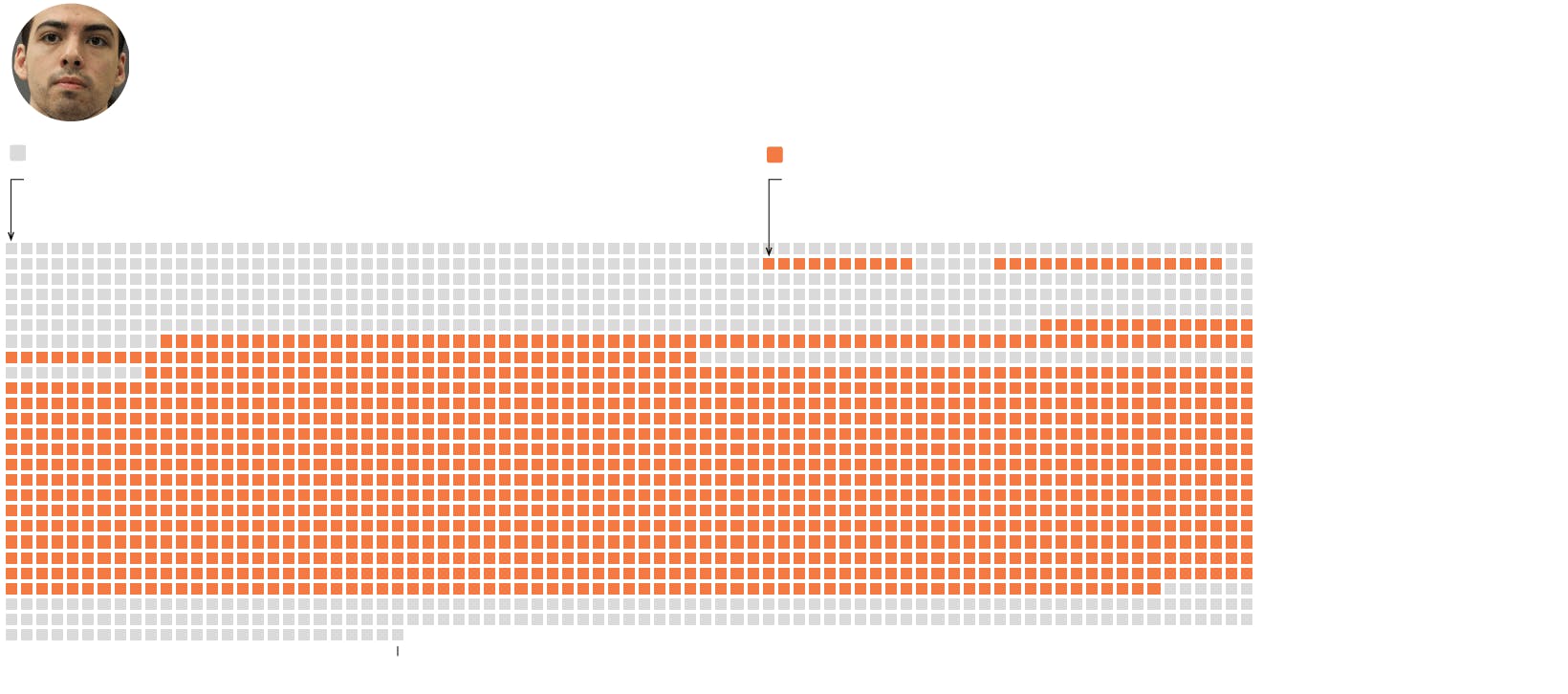

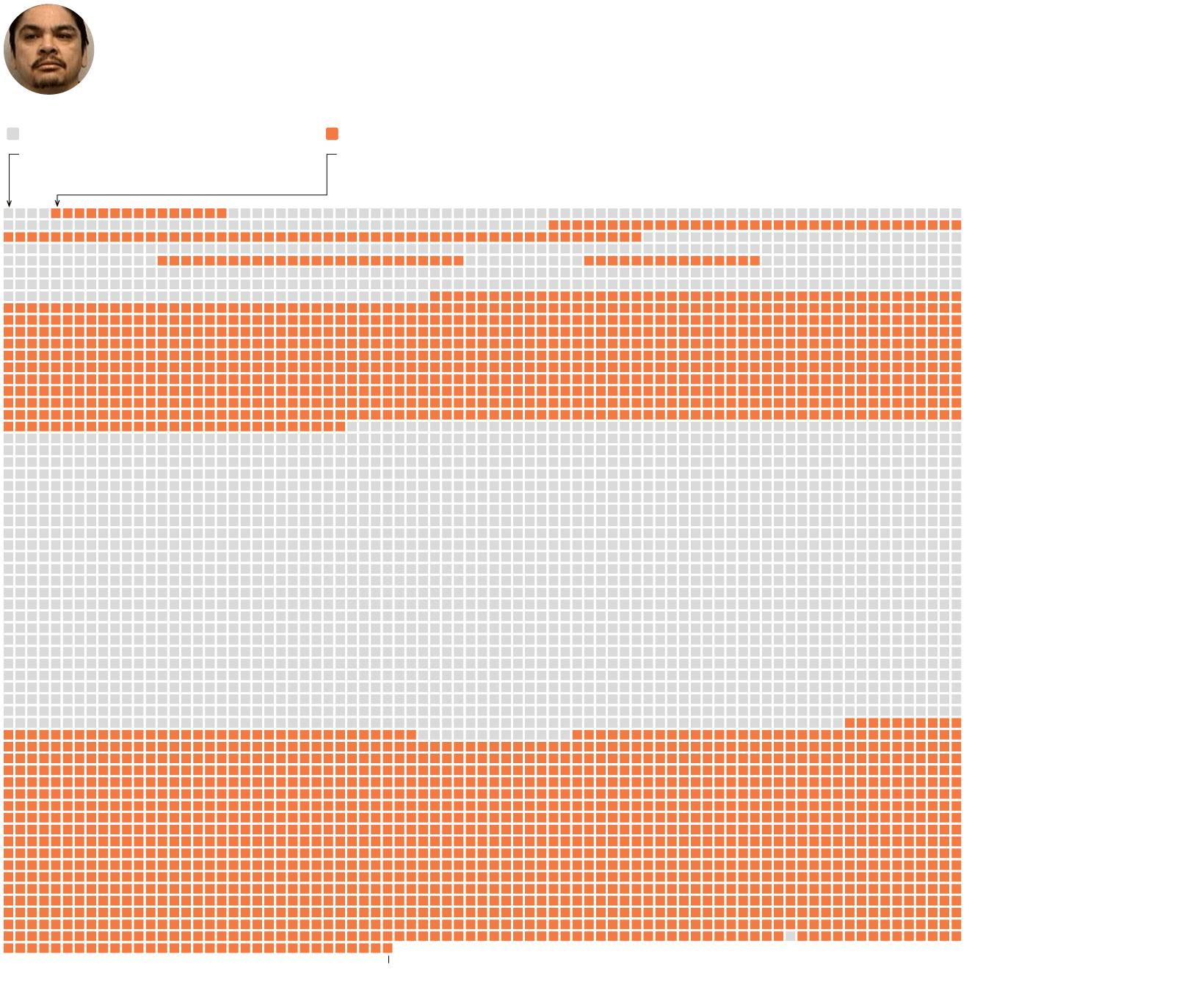

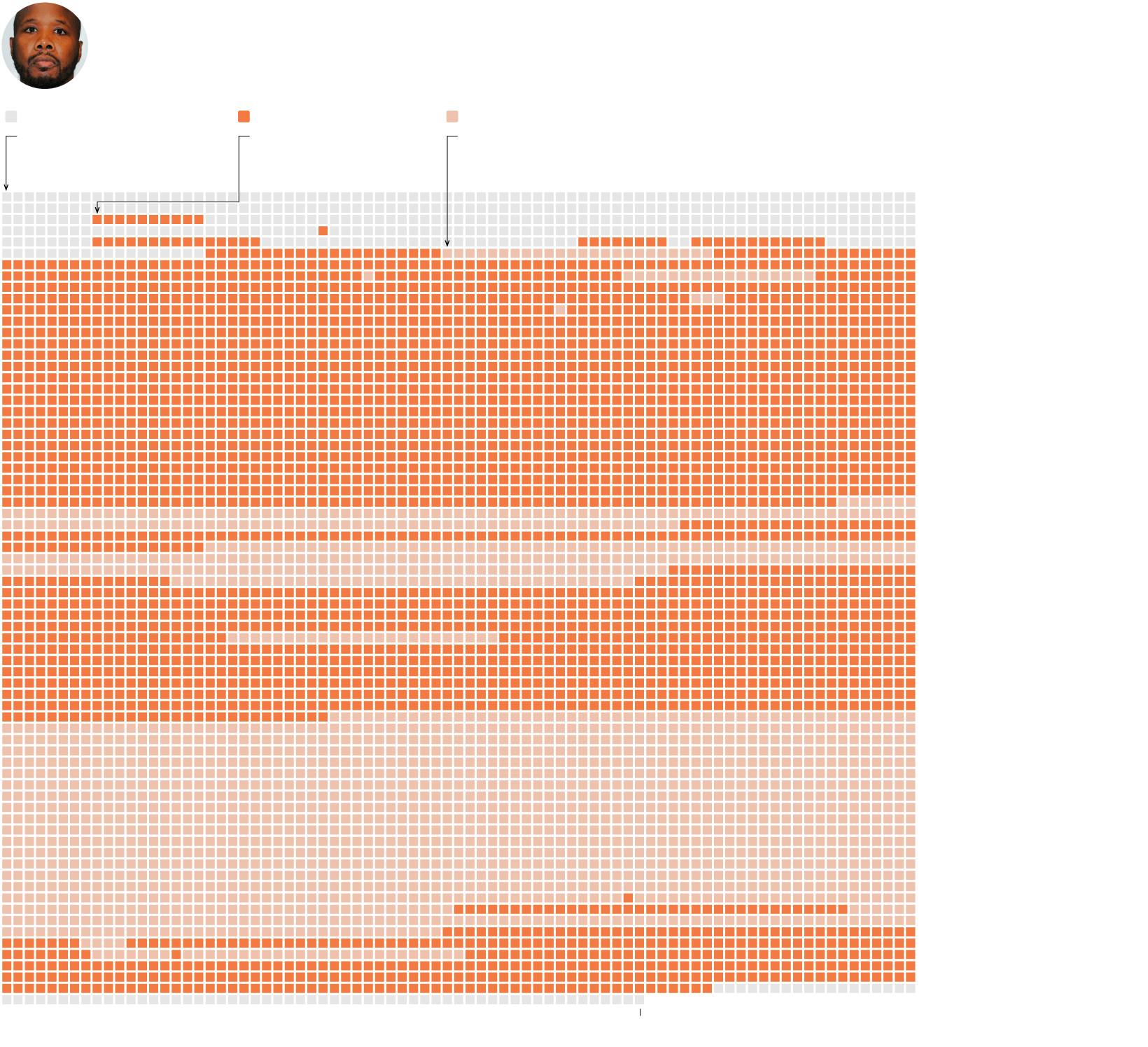

Anthony Nasseff: Nearly 70 percent of his prison time

(1,395 of 2,050 days) was spent in solitary confinement.

Prison

Solitary

Nasseff began his

sentence May 21, 2010.

His first day in solitary

was Sept. 28, 2010.

10 days

Time spent in his first solitary term, for possessing contraband.

27 terms

Includes 9 terms of solitary for threatening others and 7 terms for disorderly conduct.

240 days

Time in solitary for his most serious infraction, threatening others.

December 31, 2015

Anthony Nasseff: Nearly 70 percent of his prison time (1,395 of 2,050 days) was spent in solitary confinement.

Prison

Solitary

Nasseff began his sentence May 21, 2010.

His first day in solitary was Sept. 28, 2010.

December 31, 2015

10 Days

Time spent in his first solitary term, for possessing contraband.

27 terms

Includes 9 terms of solitary for threatening others and 7 terms for disorderly conduct.

240 days

Time in solitary for his most serious infraction, threatening others.

More than 1,600 inmates in Minnesota have been held in such isolation for at least six months.

Four hundred and thirty-seven have endured stays of a year or longer.

One man spent more than seven consecutive years in solitary.

Another spent longer than 10 years.

Across the country, states are taking new steps to either curtail or review solitary confinement, acknowledging that its unchecked use does not make prisons safer and may cause permanent harm to inmates. The federal government also has cut the use of solitary confinement in its detention facilities by 25 percent in recent years by banning it for juvenile offenders and adults who commit low-level infractions, and diverting inmates with serious mental illnesses.

But in Minnesota, the state's prisons continue to rely on the use of solitary confinement. The state also has no independent system to review whether such punishment was merited, nor any laws that limit who can be assigned to solitary in prison — or how long someone can spend in isolation.

As a result, the records show, what begins as days or a couple of weeks in solitary can turn into weeks, months or years, even for mentally ill inmates.

"I would be very surprised if you'd find any mental health professional that would say this is OK," said Sue Abderholden, director of the Minnesota chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. "This is absolutely detrimental to someone's mental health. It is not a practice that we should be doing in Minnesota."

State corrections officials defend their practices, saying they use solitary confinement only as last-resort discipline for difficult inmates. The Oak Park Heights prison is home to hundreds of murderers, rapists and violent assailants.

"There are some inmates who spend long periods of time because of their behavior," said Terry Carlson, deputy commissioner of Minnesota's corrections system. "If they seriously assault a staff member, if they kill another offender while they're incarcerated, they're going to be in segregation for a long time."

Killing another inmate can earn a prisoner the maximum solitary sentence of two years. But many of the longest solitary confinement sentences in Minnesota are served by inmates who commit less serious offenses, records show.

Nasseff, imprisoned for a violent knife assault, was supposed to stay in solitary for only 45 days. But while in solitary, he was cited again for "disorderly conduct." That added 10 more days to his punishment. The pattern continued: 45 days for disobeying an order; 240 days for making threats; 10 days for harassment. He ultimately racked up 20 additional sentences in solitary, each one adding more time.

By the time he got out, 45 days had turned into 1,200 days.

Inmate Timothy Medley, serving a five-year sentence for illegally possessing a firearm, followed an almost identical pattern. In July 2009, the department sent Medley to solitary for a 15-day stint for possessing alcohol. Like Nasseff, he continued to get in trouble in solitary, ultimately picking up 41 more terms while serving his punishment. And like Nasseff, each infraction meant more days in solitary.

Medley spent four straight years in solitary — twice as long as the sentence for a prisoner who kills another inmate.

Minnesota has sentenced more than 17,500 prisoners to solitary confinement over the past decade. Now it is among a shrinking number of states with no laws directly addressing the use of solitary in prisons.

"Why aren't we having that conversation here?" asked Susan Miles, a Washington County judge who regularly sees inmates who have been in solitary. "To continue to carry this practice out as if this were the Dark Ages — and nobody should be looking — is frankly immoral."

'A huge concept of escapism'

In an interview at Oak Park Heights prison, Nasseff, who suffers from several mental illnesses, attributed his misbehavior to prison medical staff refusing to refill his seizure medication. He said he grew ill-tempered and threatened staff who didn't help.

OFFENSES AND TIME IN THE HOLE

| Most common violations/offenses | |

|---|---|

| Disorderly conduct | 30,000 |

| Possession of alcohol, intoxicants, illegal drugs | 5,369 |

| Possession of contraband | 5,335 |

| Being in unauthorized area | 4,922 |

| Most serious violations/offenses | |

|---|---|

| Assault with a weapon on staff or inmate |

595 |

| Homicide | 67 |

| Holding hostage | 33 |

| Riot | 72 |

For each new infraction, inmates like Nasseff attend a disciplinary hearing, which is governed by a single high-ranking lieutenant, or for some major offenses, an outside hearing officer. The prisoners are not allowed lawyers in most cases, but have the option to bring a prison staffer as an advocate. If they reject an offer, similar to a plea deal, and try to fight the accusation, they risk harsher discipline. Nasseff spent 18 months of his sentence in Oak Park Heights' supermax solitary wing, formally named the Administrative Control Unit. Inmates call this infamous unit "ACU" for short, though some prefer "the hole within the hole" for its extreme isolation, even relative to other solitary units. One prison commissioner called it "the most restrictive environment in the whole state of Minnesota."

"ACU is hellish," said Brad Colbert, who runs a law clinic for inmates at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, "and there is no other way to describe it."

Inmates like Nasseff spend just an hour a day outside their small ACU cells — and sometimes less. They are supposed to get an hour of recreation time five days a week, but they are sometimes deprived of even that due to staff shortages at prisons, department officials said.

Nasseff passed the days in solitary by exercising and reading — mostly genres like science fiction, romance or westerns. During warmer months he'd spend hours watching birds play in a bush outside his narrow-slit window.

Anything to help him forget where he was.

"There's a huge concept of escapism," he said. "There's no way that I would want to live in the reality of solitary confinement."

The practice of using solitary confinement to punish prisoners existed before Minnesota was even a state. The first prison, built in Stillwater in the 1850s, included cells to isolate problematic inmates, officially called "the dungeon." Fighting, irritating a guard or using profanity could buy an inmate days or a week in the poorly ventilated, 5-by-7-foot cells. Inmates wore black-and-white striped jumpsuits, and most survived on bread and water. The well-behaved ones got soup and hot milk; those who continued acting out got handcuffed to the bars in their cells.

Inmates rejected solitary from the beginning. In one case, an inmate refused to obey an officer in the dungeon, and bought more time for calling him a "son of a bitch," according to prison disciplinary dockets from the era. Another inmate spent so much time in solitary he could no longer stand up.

The original Stillwater prison closed in 1914, but the practice of solitary confinement remained, though the Department of Corrections has since traded the term "dungeon" for "restrictive housing." Every prison now has at least one solitary unit, and the degree of isolation varies. In the St. Cloud facility, segregation cells have barred doors, so inmates have more opportunities to communicate with each other; when the Oak Park Heights ACU is on lockdown, prisoners can hear nothing, not even footsteps outside their cell doors.

Other states reforming

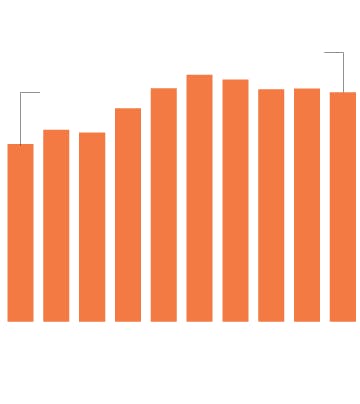

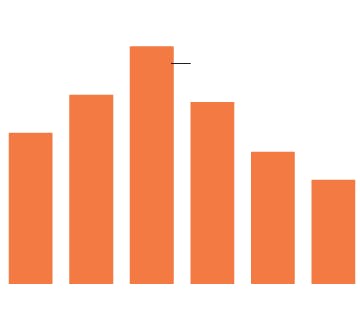

Minnesota prisons punished inmates 5,828 times with restrictive housing in 2006, according to department records. That number rose sharply over the next five years, peaking at 8,110 in 2011. It has since dropped incrementally, hitting 7,533 last year.

Carlson, of the DOC, said that inmates are taught discipline procedures upon their arrival to prison, and they know what behavior will land them in segregation. She said correctional officers try to find alternative punishments, but sometimes solitary is the only option.

Yet Carlson acknowledges flaws in the department's practices. If an inmate continues getting into trouble in solitary — in turn accruing more and more time, like Nasseff or Medley — that may be a red flag that the punishment isn't effective, she said. The department is now examining better ways to deal with these repeat offenders, she said.

HOW HEAVILY DO MINNESOTA PRISONS RELY ON SOLITARY?

"That's exactly it — finding a different way, maybe an incentive system for good behavior, rather than continuing the stacking that obviously isn't working," Carlson said.

Meanwhile, at least 30 states have put in place major reforms over the past six years. Last year, Wisconsin banned the use of solitary for minor offenses. For major offenders, like those who kill another inmate in prison, the state's corrections secretary has to approve any stay longer than 120 days.

Thousands of Minnesota inmates have spent longer than four months in solitary confinement.

As of this summer, Nebraska mandates that solitary confinement be used in the least restrictive way possible.

California consented last year to a court settlement that will drastically overhaul its use of solitary. Under the historic agreement, California can send only the most serious offenders to solitary and the state will build a new unit that allows more socialization, group activities and time out of cell for inmates deemed too dangerous for the general prison population.

Behind the wave of national reform is emerging research showing that long-term isolation does not make prisoners less likely to reoffend — on the contrary, some studies have found, it makes them even more likely to be arrested after release. The practice can also cause devastating psychological damage, which is why many states have focused on banning or limiting its use for inmates with mental illnesses.

One of the most damning assessments of prisoner isolation came in 2011, when a special investigator for the United Nations denounced it as a degrading punishment, declaring that any stay in excess of 15 days can amount to torture.

Minnesota has given out terms of that length or longer more than 24,000 times over the past decade.

"What's surprising about Minnesota is that they've taken so few steps to reform," said ACLU attorney Amy Fettig, senior staff counsel for the ACLU's National Prison Project. "If Texas is reforming, if Mississippi is reforming and Minnesota doesn't even have it on their radar screen, you gotta wonder what's going on there."

A judge takes a stand

Susan Miles sees up close the toll deep time in solitary can take on a man.

The judge's chambers on the fifth floor of the Washington County Courthouse overlook the idyllic St. Croix River Valley, which, beyond its antique stores and river-view condominiums, is home to the Oak Park Heights and Stillwater prisons. Collectively, these two facilities hold about a fifth of Minnesota's inmates, among them the state's most serious offenders. When a prisoner is charged with another crime inside either facility, or files a claim of wrongful imprisonment, there's a good chance he'll end up in front of Miles.

In 2012, a man named Cesar de la Garza appeared in her courtroom. De la Garza faced charges for punching a correctional officer in the face, a felony that carried another year in prison. She watched De la Garza deteriorate from well-groomed and well-spoken to disheveled, 30 to 40 pounds lighter and struggling to speak coherently. Around that time, she read the United Nations' report classifying more than 15 days as torture.

"That's when the light bulb went off," she recalled, "and I said, 'Wait a minute, this is going on routinely across the street from the courthouse, and nobody's paying any attention.' "

De la Garza had already spent 2 ½ years in the hole by the time he arrived in Miles' courtroom. In addition to going back to solitary as punishment for the recent assault, the DOC had already extended his prison time by a year. If he was convicted of the assault charge, he'd spend yet another year in prison.

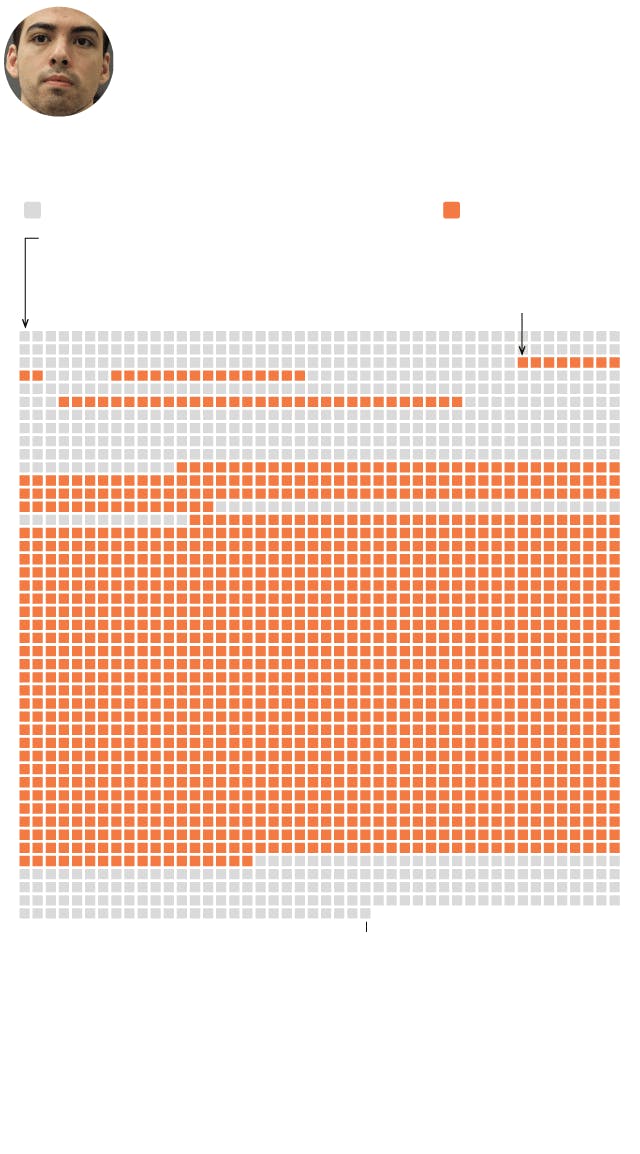

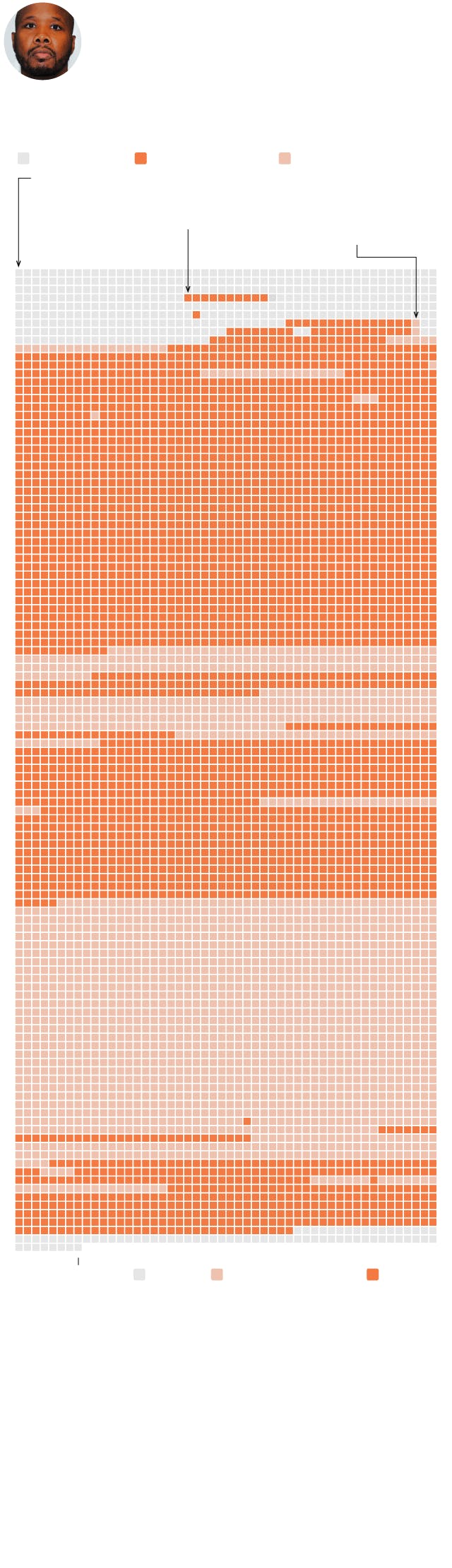

Cesar de la Garza: Out of 5,055 days in prison, almost half (2,516 days) were in solitary confinement.

Prison

Solitary

De la Garza began his prison sentence Feb. 27, 2002.

His first day in solitary was March 3, 2002.

15 days

Length of De la Garza's first term in solitary, for disorderly conduct.

48 terms

This includes being placed in solitary 12 times for disorderly conduct.

450 days

Time in solitary for his most serious infraction, attempted homicide.

December 31, 2015

Cesar de la Garza: Out of 5,055 days in prison, almost half (2,516 days) were in solitary confinement.

Prison

Solitary

De la Garza began his prison sentence Feb. 27, 2002.

His first day in solitary was March 3, 2002.

Prison

Solitary

December 31, 2015

450 days

Time in solitary for his most serious infraction, attempted homicide.

15 days

Length of De la Garza's first term in solitary, for disorderly conduct.

48 terms

This includes being placed in solitary 12 times for disorderly conduct.

De la Garza fought the charges from his cell in the ACU. He said the officer provoked him by calling him names. He represented himself with assistance from attorney Rebecca Waxse, but when Waxse came to visit him they couldn't sit in the same room together to look over evidence due to security policies for solitary inmates. After months contesting the assault, De la Garza recognized a losing battle and pleaded guilty.

But on the day of sentencing, Miles had determined to do something bold: She was going to stand up for a guilty man.

"I have to say that though I've been doing this job for going on 17 years now, this is a case in which the issue of solitary confinement and its impact on an inmate grabbed my attention," she told the court. "So I did a little digging."

She began by citing a Supreme Court case from 1890, which found inmates experiencing even short terms in solitary became "violently insane," and in some cases committed suicide.

She read from the U.N. torture report, which called solitary confinement "A harsh measure which is contrary to rehabilitation, the aim of the penitentiary system."

She quoted from a study by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which concluded solitary "always constituted cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and even torture when applied to persons with mental disabilities."

She pointed out De la Garza deteriorated mentally from spending so many years in isolation already. A common symptom of long-term solitary was the type of irrational violence that led to this charge. It was clear, she concluded, that solitary had "a deleterious impact on Mr. De la Garza's mental state leading up to this offense."

Miles ordered that De la Garza serve the extra year in prison concurrently with his sentence, meaning he wouldn't spend more time behind bars for the assault.

The state appealed Miles' decision to a higher court and won. When the case came back to her courtroom for resentencing, the best Miles could offer was a reduced prison time tacked onto his sentence.

By the time the cases finished, De la Garza had spent another year in solitary for the assault. In 2015 the DOC shipped him to a prison in Pontiac, Ill., through an inmate-swapping program. There, he continued to serve time in isolation, bringing his total time in solitary to more than six years since arriving in prison in 2000.

An evolving philosophy

The tectonic shift in philosophy over solitary confinement isn't bound by political affiliation.

In recent years, major political figures from both sides of the aisle have spoken out publicly against the practice. This includes conservative billionaire funders Charles and David Koch, who have bankrolled a lobbying push for prison reform, including solitary confinement practices. President Obama denounced the practice earlier this year when he enacted a ban on solitary for juveniles in the federal prison system.

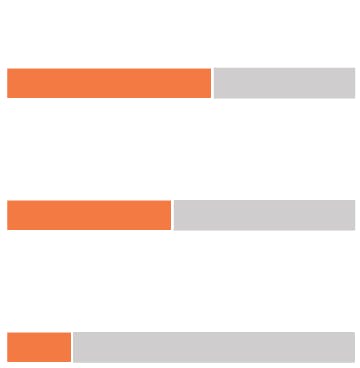

INMATES BY RACE

"How can we subject prisoners to unnecessary solitary confinement, knowing its effects, and then expect them to return to our communities as whole people?" Obama wrote in a Washington Post editorial. "It doesn't make us safer. It's an affront to our common humanity."

In Minnesota, corrections officials say they are constantly monitoring their policies and trying to calibrate based on national trends. They are looking at recommendations put forth by the White House — the same that led to the 25 percent decrease in federal prisons — said Bruce Reiser, assistant corrections commissioner.

"It's the right thing to do," Reiser said. "Based on national standards and all the studies that say isolation is detrimental to the offenders that are in segregation, it was just time for us to take a look at how we're managing our segregation units."

The department has tried to get help from the Legislature. In the 2016 session, corrections officials asked lawmakers for funding to expand mental health services for solitary inmates and hire more correctional officers, which could allow for more constructive programming. But the request fell by the wayside in a contentious legislative session. Commissioners say they will ask for money again in 2017.

In September, after months of inquiries from the Star Tribune, the department sent a memo to staff and inmates announcing it will limit single solitary terms to 90 days — down from the previous maximum of two years. However, the change is not retroactive. Inmates can also still rack up additional time if they break rules in solitary. If prisoners stay in for six months, they will be eligible for a "step-down" program, in which they will be able to earn more privileges through good behavior and completing assignments, and then transfer back to general population with some restrictions. No inmates have gone through this program yet, and corrections officials say they're still working out the details.

Without giving specifics, Carlson said the department plans to make more changes gradually, though some depend on funding.

"I think it will change," she said. "I don't want to say it won't happen anymore, because if an offender continues to be really assaultive, we need to protect staff and offenders. At the same time, we know that there's always room for improvement."

Starting new

After spending four years in solitary, Cesar de la Garza was finally transferred to his prison's general population this summer. But the relief was short-lived. After two weeks, the Illinois prison threw him back in solitary.

The Illinois Department of Corrections denied the Star Tribune an interview with De la Garza, and department spokeswoman Nicole Wilson refused to explain why. Wilson also would not say why mail from De la Garza frequently came months later than dated. Meanwhile, De la Garza recently filed his 12th federal lawsuit challenging his living conditions in prison — including solitary. None has been successful. With good behavior, he is expected to be released from prison in 2021.

Nasseff has had better luck. Earlier this year, the department sent him to general population on a probationary basis. If he misbehaves, he could go back to solitary.

So far, he's managed to stay out of trouble, which he credits to finding God in those years of reading in solitary. He's since earned his GED and works a job in the prison's canteen department. He's being treated for several mental illnesses, including PTSD, anti-social behavioral disorder and substance abuse.

Nasseff is scheduled for release in 2019. Once he's finished supervised release and is completely free, he plans to get as far away from Minnesota — and the Oak Park Heights prison — as possible.

"I'm hoping Alaska," he said. "I just see it as a better chance to start new — fresh. I just want to live off the land."

Minnesota's state prisons are routinely sending inmates with serious, chronic mental illnesses to stays in solitary confinement that can last months or years, even as records show that such extended, harsh punishment can make their conditions worse.

Israel Musawwir spent about nine years in isolation — longer than any inmate in the recent history of Minnesota prisons — even with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Not long afterward, he was smearing his feces on the walls of his cell.

Alexander Mooney spent about 100 days in solitary from August 2014 to January 2015. He killed himself last year, less than two months after his release from prison. The death record cites "history of psychiatric illnesses" as a secondary cause of death. He was 26 years old.

There is no official count of how many people with preexisting mental illnesses have been punished with solitary confinement by the Minnesota Department of Corrections. But nearly 2,500 of 17,500 prisoners who have served time in isolation have been recommended for state-ordered mental health treatment — known as a "civil commitment" — according to a Star Tribune analysis of 10 years' worth of prison and civil documents.

Of those sent to solitary confinement in Minnesota from 2006 through 2015, at least 39 have since killed themselves, according to Department of Health records. Some suicides occurred weeks after release from solitary, others years. In many cases, the Health Department lists a mental illness as a cause of death.

Mental illness permeates every level of the state's corrections system. A report this year by the Minnesota Legislative Auditor found that nearly two-thirds of those deemed mentally incompetent to stand trial were jailed while courts decided whether to commit them to treatment, which is in violation of state law.

Minnesota correctional officials defend placing inmates with mental illnesses in solitary confinement. Prison therapists regularly visit inmates while in isolation, and will transfer them to the facility's Mental Health Unit — an inpatient wing of the prison — if their condition worsens, said Bruce Reiser, assistant corrections commissioner.

Reiser said barring the use of solitary for mentally ill inmates would jeopardize the safety of prison staff and other inmates.

"We're pretty black and white when it comes to maintaining the safety and security of the facility," he said.

The federal government and several states, including neighboring Wisconsin, have curbed the use of solitary as a way to discipline seriously mentally ill inmates, acknowledging the punishment has been overused. Keeping prisons safe and giving inmates better mental health care don't need to be mutually exclusive, said Dr. Kenneth Appelbaum, a psychiatrist with the Center for Health Policy and Research at the University of Massachusetts, who has worked on the issue in other states.

"The argument that somehow you've got to do this — you need to put people into these conditions of extreme isolation and social deprivation in order to keep them and everyone else safe — is a bankrupt argument," said Appelbaum. "It's simply not true."

Nine years of solitude

In Musawwir's case, there was plenty of evidence to suggest mental illness before he ever got to prison.

Musawwir agreed to turn his medical records over to the Star Tribune. The documents chronicle the devastating impact of long-term solitary on the psyche of someone already living with a debilitating mental illness.

As a teenager, Musawwir began experiencing paranoid hallucinations. When he was 19, he became convinced a friend hired an assassin to kill him, and in what he later described as an act of self-defense, shot the man to death, according to criminal charges.

Ramsey County prosecutors charged Musawwir with second-degree murder, and while he awaited trial, the state committed him to the Minnesota Security Hospital in St. Peter, where doctors diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia. His attorney argued Musawwir lacked the mental competency to understand his crime, and asked for leniency. But after testimony of Musawwir's drug use, including smoking marijuana laced with embalming fluid, the judge sentenced him to 27 years in prison.

Once he was in the Oak Park Heights maximum security prison, doctors began treating him for schizophrenia, paranoid personality disorder, anti-social personality disorder and substance abuse. In those early days, they described him as "well groomed," "logical" and "organized."

But Musawwir started getting in trouble with prison staff almost immediately. In fall 2000, a lieutenant sent Musawwir to solitary confinement because he refused to stop profanely rapping in his cell.

His condition began to worsen, especially when he refused to take his medication. In February 2001, one doctor predicted Musawwir's symptoms "will begin to increase more markedly," suggesting he should stay in the prison's mental health unit until they could get a court order to forcibly medicate him.

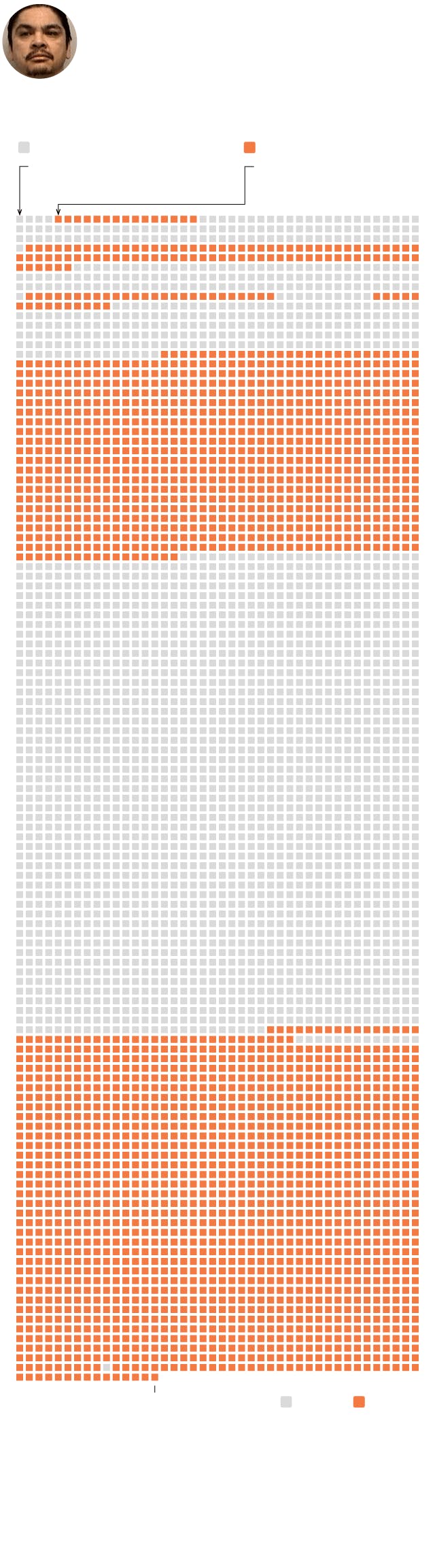

Israel Musawwir: Of his 5,809 days in prison,

about 56 percent (3,270 days) were in solitary confinement.

Solitary

Mental health unit

Prison

Musawwir began his prison sentence Feb. 9, 2000.

His first stay in solitary began July 24, 2000.

Musawwir was admitted to the mental health unit for the first time April 24, 2001.

15 days

Time spent in his first term of solitary, for harassment.

162 terms

Includes being placed in solitary 70 times for disorderly conduct.

360 days

Time in solitary for his most serious infraction, assaulting staff.

2,087 days

Time in mental health unit. He repeatedly requested permanent move to the prison's in-house unit, but was repeatedly shuffled in and out of solitary.

3 years

His longest stint in the mental health unit.

December 31, 2015

Israel Musawwir: Of his 5,809 days in prison, about 56 percent (3,270 days days) were in solitary confinement.

Prison

Solitary

Mental health unit

Musawwir began his prison sentence Feb. 9, 2000.

His first stay in solitary began July 24, 2000.

He was admitted to the mental health unit for the first time April 24, 2001.

Dec. 31, 2015

Solitary

Prison

Mental health unit

15 days

Time spent in his first term of solitary, for harassment.

360 days

Time in solitary for his most serious infraction, assaulting staff.

2,087 days

Time in mental health unit. He repeatedly requested permanent move to the prison's in-house unit, but was repeatedly shuffled in and out of solitary.

162 terms

Includes being placed in solitary 70 times for disorderly conduct.

3 years

His longest stint in the mental health unit.

Instead, Musawwir remained in solitary. The prison psychiatrists assigned to Musawwir couldn't be in the same room, and treated him through the metal slot in his cell door. Eventually the prison transferred him to its new "supermax" solitary unit, called the Administrative Control Unit, where he was completely isolated from sound or human contact, save for with prison staff, whom Musawwir increasingly saw as his enemies.

Because of his behavior, the DOC sentenced him to 20 years in solitary with a scheduled release in 2026.

Musawwir's doctors' notes detail how his mental condition deteriorated as he lost all hope of getting out.

• Feb. 21, 2006: "Seems to be slipping emotionally/mentally in that he does not believe anything he does will make a difference in his incarceration ... Is thinking of going off meds as he does not see that it makes any difference. Does not see any point in continuing with psych services."

• March 8, 2006: "Mr. Musawwir has been doing everything he can possibly do to comply with rules and regulations. I have concern that he will be losing complete sense of hope if he is unable to actively see change."

• July 3, 2009: "Mr. Musawwir's thinking is very closed and he is in great distress."

In February 2011, a doctor noted that due his mental illness and the stress endured over such a long time in the ACU, "a psychosis did occur."

Out of asylums, into prisons

Mooney, originally sent to prison for domestic abuse, bounced back and forth between freedom and Oak Park Heights in 2015, after an extended stay in solitary.

He began experiencing paranoid delusions and attempted suicide several times that year. In one case, he tried cutting his throat during a standoff with police outside Regions Hospital.

He succeeded less than two weeks after getting out of prison in September of last year, when he was found dead in his backyard in Apple Valley. He maimed his girlfriend in the process, but she survived the attack.

Documentation of solitary confinement's harmful effects has been around for more than a century, but until recently the American correctional system has largely ignored it. From 1995 to 2000 alone, the number of prisoners in solitary in the United States surged nearly 70 percent, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Part of the increase was driven by the high rate of mental illness among prisoners. Throughout the 1960s and '70s, the United States phased out its so-called mental health "asylums," abandoning the philosophy that people with severe psychological illnesses should be locked up indefinitely. The shift meant more humane treatment of these patients, but it also coincided with the beginning of the largest prisoner influx in the history of the United States.

One national study, conducted by the Treatment and Advocacy Center, found that about 35,000 people with severe mental illnesses resided in state hospitals in 2012. Meanwhile, more than 356,000 — roughly the population of Minneapolis — were confined to prisons or jails unequipped to deal with them. Inmates with debilitating mental illnesses frequently act out in the volatile prison setting. The behavior lands them in places like the ACU, where they often remain because the prisons deem them a risk to the other inmates and staff.

"We try to work with them, to stabilize them, to get them back out into the general population, but sometimes they relapse and they end up moving back and forth to ACU [and the mental health unit]," Reiser said. "We can't move them out into general population because of the safety issues that go along with it — because of their behavior."

Lawmakers in Minnesota have yet to address the practice of isolating problematic prisoners — let alone creating specific policies to protect the most vulnerable inmates. And there's no concrete evidence to suggest the practice of isolating mentally ill inmates makes prisons safer. In his 10 years working for Massachusetts prisons, Appelbaum saw time and again the impact of solitary on patients with mental illnesses: "They are certainly not going to get better under those conditions, and there's a high likelihood they're going to get worse."

Abandoning all hope

In an interview at Oak Park Heights this summer, Musawwir said he started to "lose it" after the prison moved him to the ACU in 2003.

"I didn't hear voices until I got to ACU and I was back there that long," he said. "And I started to hear them real bad. It got to the point where I went on hunger strikes."

He described increasing anger over his treatment, both with psychiatric staff and the correctional officers who guarded his cell. He was moved to the prison's Mental Health Unit several times, and asked repeatedly for a permanent move there, but was always dropped back in solitary.

Physical standoffs became a regular occurrence. After picking up so much time in solitary, Musawwir lost any hope of getting out, and in turn any incentive to follow orders, he said.

"I got to the point where I said, you know what, I'm not talking to you no more," he said. "I'm just going to smear feces, and when I do that, then they'll see that I'm not doing well."

While he became more combative, his mental health worsened. Less than two years after being described as logical by prison psychologists, Musawwir was regularly throwing feces and urine at staff, hoarding garbage and milk cartons in his cell and masturbating in front of his doctors.

One day, in March 2005, he covered the camera in his cell with wet paper, wiped soap over the window on his cell door and barricaded the metal slot with his mattress, blankets and a pillow. When the correctional officers asked him to come out and accept restraints, he shouted for them to "Get suited and booted," according to a criminal complaint. The officers put on helmets, gas masks, vests, gloves and leg and elbow pads and tried to feed a tool into the cell so they could fill it with chemical irritant. But when an officer opened the metal slot, Musawwir threw a cup containing a mixture of urine and feces at his head.

On four separate instances, Musawwir was charged with felony fourth-degree assault of an officer, and he picked up more than two additional years in prison. The charges also meant more solitary time and the loss of small privileges like books, visits with family and daily exercise time.

Musawwir ultimately spent 14 years between solitary confinement and the mental health unit.

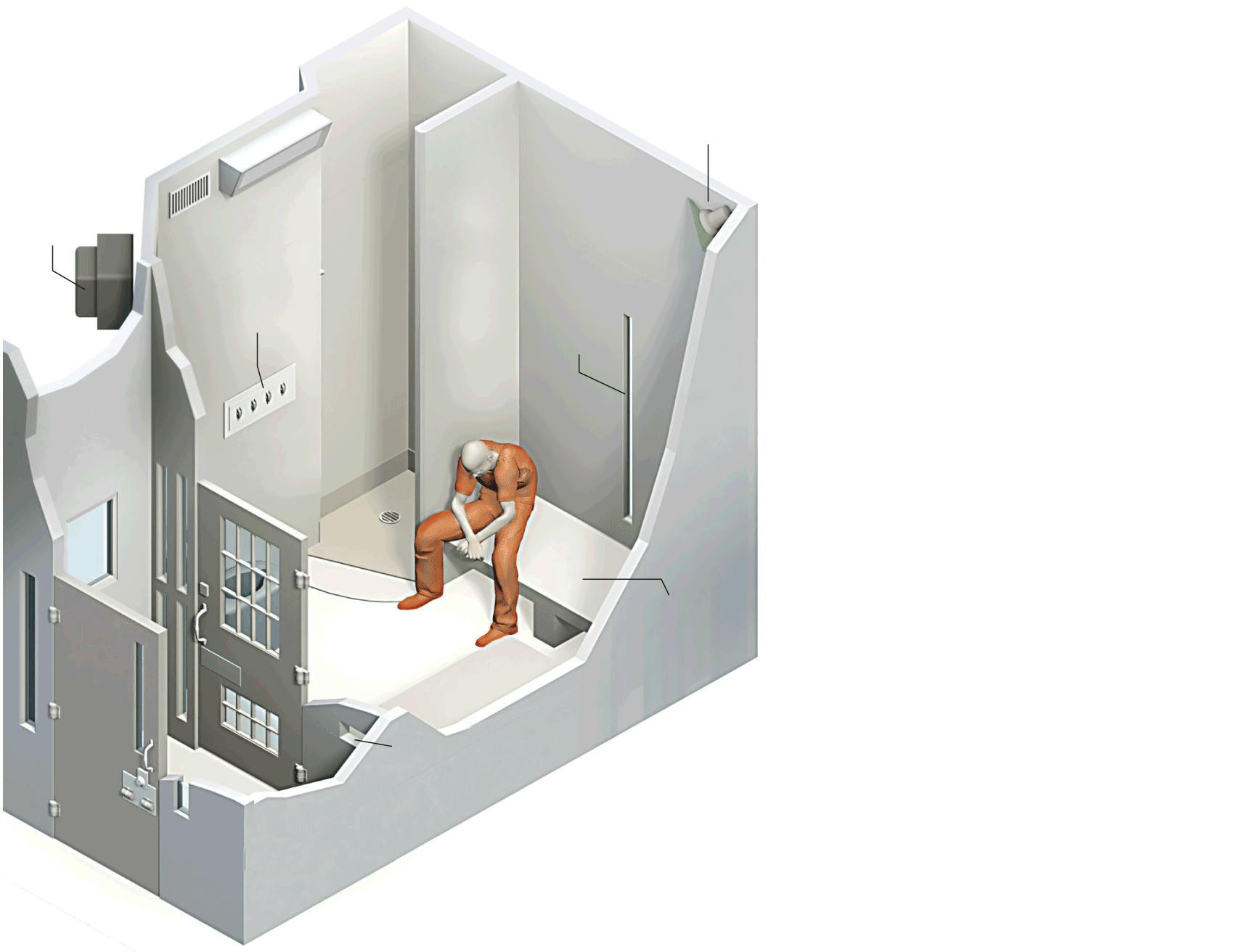

Inside the 'hole'

The Oak Park Heights prison, Minnesota's only maximum security prison, places its most dangerous inmates apart from its other 400 prisoners in solitary confinement cells.

Inmates sent to the prison's "supermax" unit end up in one of 60 solitary cells, where they spend 23 hours a day in a space smaller than the average bedroom.

For one hour each day, inmates in solitary are allowed access to a common space that includes an exercise area. Some inmates are granted access to television and radio.

Each cell contains:

• Double-door controlled entry

• 95 square feet (11-by-8.5 feet)

• Wall-mounted radio

• Intercom

• Table/bench

• Air vent

• Toilet

• Light

Shielded

camera for

24-hour

surveillance

TV behind

shatterproof

glass

Breakaway

hanger

hooks

Exterior

window

Shower

stall

Bed with

thin mattress

Access slot for

meals/telephones

Sources: Oak Park Heights prison,

news interviews

MARK BOSWELL • Star Tribune

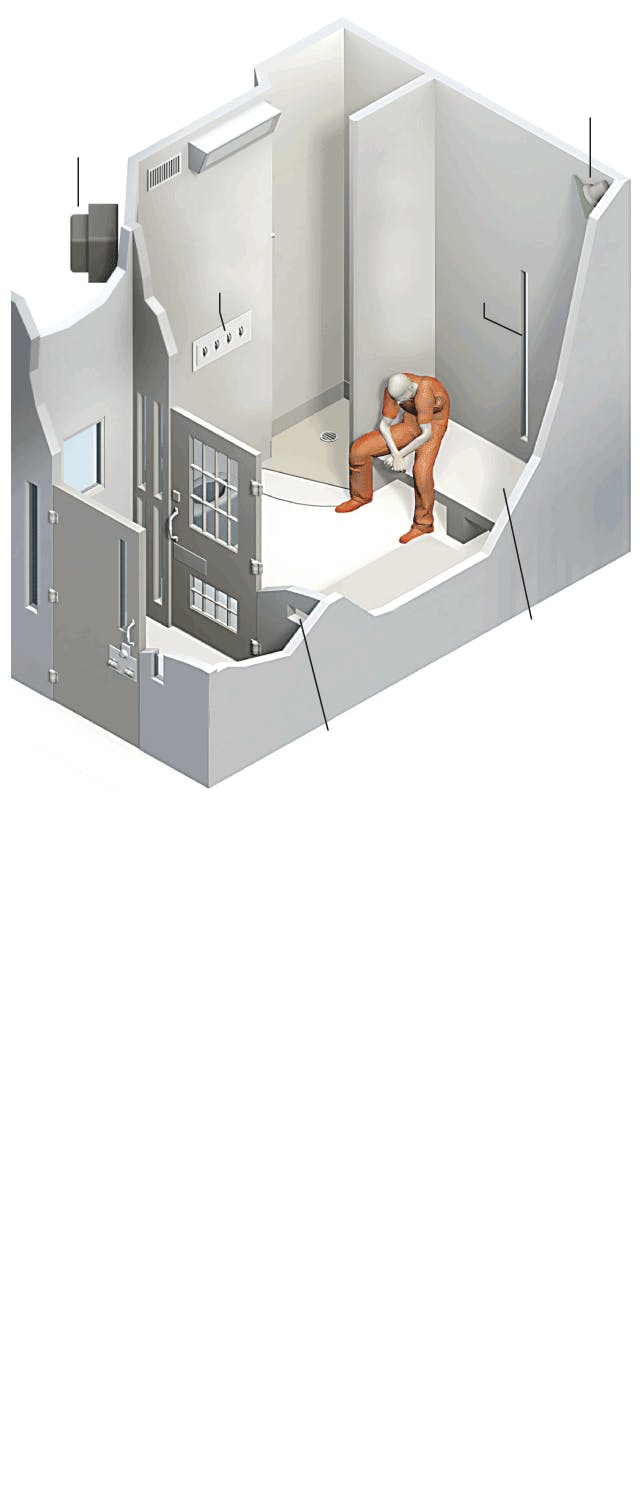

Inside the 'hole'

Shielded

camera for

24-hour

surveillance

Shower

stall

TV behind

shatterproof

glass

Breakaway

hanger

hooks

Exterior

window

Bed

with thin

mattress

Access slot for

meals/telephones

The Oak Park Heights prison, Minnesota's only maximum security prison, places its most dangerous inmates apart from its other 400 prisoners in solitary confinement cells.

Inmates sent to the prison's "supermax" unit end up in one of 60 solitary cells, where they spend 23 hours a day in a space smaller than the average bedroom.

For one hour each day, inmates in solitary are allowed access to a common space that includes an exercise area. Some inmates are granted access to television and radio.

Each cell contains:

• Double-door controlled entry

• 95 square feet (11-by-8.5 feet)

• Wall-mounted radio

• Intercom

• Table/bench

• Air vent

• Toilet

• Light

Sources: Oak Park Heights prison, news interviews

MARK BOSWELL • Star Tribune

Alternatives to solitary

Three years ago, Colorado came under fire from human rights organizations for its aggressive use of solitary in a supermax unit similar to the one Musawwir lived in.

On any given day in 2012, between 537 and 686 mentally ill prisoners were held in isolation, staying a median of 16 months, according to a report from the ACLU.

Now Colorado is among states pioneering alternatives to solitary.

In 2014, the state Legislature banned placing inmates with serious mental illnesses in solitary. The prison system also created a new unit called a Residential Treatment Program. Inmates with mental illnesses are segregated from general population, but they still go to classes and spend more time out of their cells with other inmates. They are also guaranteed adequate mental health care time each week.

Colorado prisons have cut their solitary population by two-thirds since the ban. And it's not just Colorado. Earlier this year, North Dakota's Department of Corrections made a similar and perhaps even more dramatic overhaul: It flipped its solitary unit into a rehabilitation hub that offers group services like activities and psychological treatment.

"There are places that are trying to deal with these issues, some of them on a fairly shoestring budget," said Laura Rovner, who runs a civil rights clinic through the University of Denver's law school. "The answer is not just, well, we've got a problem, and when all you have is a hammer, which is solitary confinement, everything looks like a nail. There are other tools. And hopefully Minnesota will start using them."

In late 2014, Oak Park Heights prison finally moved Musawwir out of solitary confinement on a probationary basis, meaning he will go back if he gets in trouble again. He is expected to be released from prison in 2028.

After years of therapy, he said the voices have subsided. He's been in general population for more than a year and is working toward earning his GED. He credits his recovery to finally getting released from the isolating conditions of solitary confinement and into a social environment. He struggles to comprehend why they kept him in solitary for so long.

"If you see a person in a situation where they're not getting better, they're actually getting worse, why would you keep them in that situation?" Musawwir asked. "You get to a point where you just don't care anymore."

It's Christmas Eve in the hole, and Keegan Rolenc hears familiar moans and cries for help from down the cell block. He figures it's because starting tomorrow the unit will go on lockdown for three days. No calls, no mail, no exercise time. Worse yet: The guards close both doors to the cells, so inmates in solitary confinement hear nothing but their own thoughts.

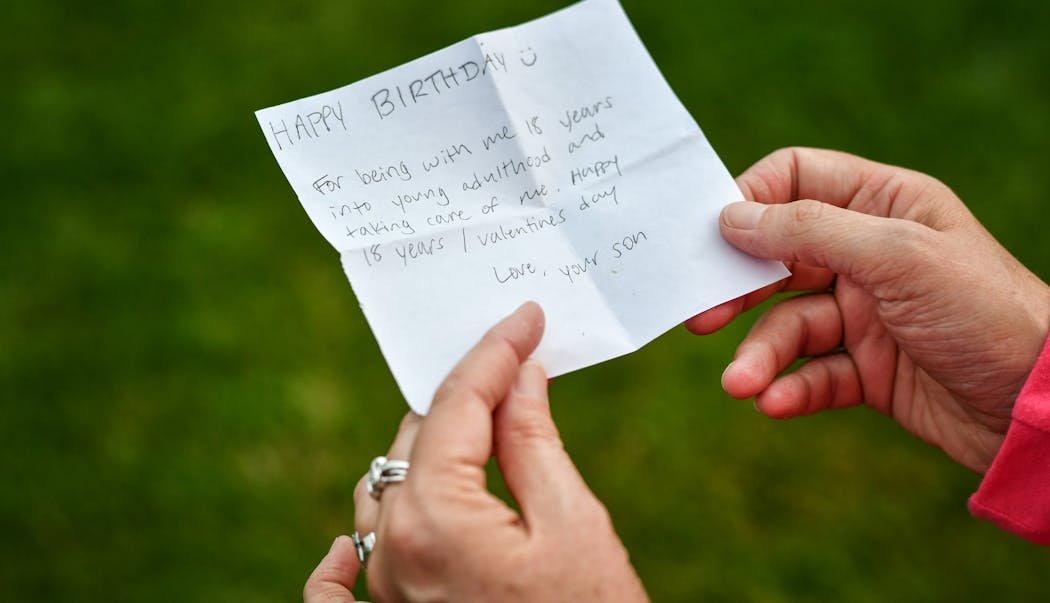

Rolenc has been in solitary for a month now, with 11 more to go. Already, his mind is playing tricks on him. He hardly sleeps, and when he does he has nightmares that he gets out of prison and the cops bust him with a pistol. He runs away but they always catch him.

He promises himself that won't happen. Tomorrow will be the third Christmas in a row he's missed with his son, and that's enough.

When I step foot out of these gates I never want to see the inside of a jail or prison another day in my life, he writes in his journal. I know it's all on me. I gotta make that a reality.

In November 2015, the Minnesota Department of Corrections sentenced Rolenc, a 23-year-old Minneapolis man, to a year in solitary confinement for assaulting his son's mother during a visit. He will serve most of that sentence in a cell the size of a small child's bedroom. He will be alone for 23, sometimes 24 hours a day. Over the course of a year, he will be permitted one visit, from his mother and his 5-year-old son.

Rolenc's was one of the 7,500 solitary sentences handed to Minnesota prisoners last year alone; he among an estimated 100,000 serving time in isolation around the country. His punishment comes when many states are reconsidering the practice of isolating prisoners. At least 30 have passed new laws or policies limiting how prisons can use solitary confinement to punish inmates. Minnesota, where more than 400 prisoners have spent at least a year in solitary during the last decade, is not among them.

The Star Tribune spoke to dozens of inmates who have served lengthy solitary sentences. In letters, phone calls and supervised interviews in prison they described the torment of spending months or years alone in closed quarters, under perpetual supervision and with little or nothing to occupy their mind. Some told of the psychosis that ensued. One man said he passed the time by killing small bugs he found in his cell. Another likened his experience to a caged lion at the zoo. "He just give up on life," he wrote. "If you try to let him out in the jungle, he won't be able to survive."

The Department of Corrections denied an in-person interview with Rolenc, who was released from solitary in late November, citing potential further trauma to his victim. To tell his story, Rolenc agreed to share family letters and his handwritten journal in which he meticulously documented life in the hole. Together, they provide a rare, real-time glimpse into the mind of a person living in long-term isolation.

This isn't for the weak minded or weak hearted, Rolenc writes. Back here it's a regular occurrence for dudes to snap and sling feces all over their cell, eat feces, smear it on their body ... It's the monotony, the boredom, the hopelessness, the helplessness, the anger, the frustration, the loneliness, being tired of the same thing day in and day out for days, months, years that brings them to the breaking point.

A fight — and punishment

It's late November 2015, and Rolenc sits in the disciplinary unit of the Faribault prison. When he closes his eyes, he sees the horrific incident that landed him in solitary. The guilt is heavy, like waves crashing against the inside of his skull.

His son, Jamaal, and his son's mother, Shay, had come to visit here in Faribault, where Rolenc is serving four years for shooting up a car and house. Rolenc and Shay argued. Shay hit him in the head and kicked him in the shin. When Rolenc got up to end the visit, she slapped him with an open hand across the face, according to prison disciplinary documents.

I lost it, Rolenc writes. I punched her a couple times then threw her on the ground and stomped her a couple times (not in the head though) ... afterwards I couldn't believe what I had just done. In front of my son. To his mom.

Two weeks later, he is summoned to an in-house disciplinary hearing. Rolenc does not have a lawyer with him. The prison charges him with assault, aggravated assault, attempted homicide and disorderly conduct. They offer him 360 days in the hole, with 120 days added to the four years he started serving in 2012. If he tries to fight it, they could push for an even longer stay in solitary. He signs the contract but wonders if he made a mistake.

I probably should've got some type of legal advice ... but I just wanted the s*** to be over and the 'not knowing' was killing me.

He goes back to his cell and thinks about the time.

360 days. 12 months. 52 weeks.

He questions whether he will stay sane. Maybe this will make him stronger, like a mental test.

On Dec. 9, 2015, the officers come to collect Rolenc, and he sees the letters "OPH" emblazoned on a bag. He realizes they're sending him to Oak Park Heights, Minnesota's maximum security prison. They bring him directly to the Administrative Control Unit — the "ACU" — the strictest lockdown isolation unit in the state.

Ain't no telling what I'll be after being here for a year, he writes.

Losing the way

Forty miles from the Oak Park Heights prison, on a block of one-story bungalows in south Minneapolis, a letter arrives in Sharon Rolenc's mailbox.

It's from her son. He asks if she will teach him to cook when he gets out of prison so he can make breakfast for Jamaal. He wants to make French toast. Even weeks later, Sharon tears up at the sentiment.

Sharon, who works in communications for a Twin Cities college, always thought Keegan would be a Rhodes scholar — not a criminal. She tries to pinpoint the moment things went so wrong.

Keegan grew up in middle-class Minneapolis neighborhoods, and Sharon recalls his exceptional acumen for academics at a young age. In elementary school, he started taking classes with students in the grade ahead. He excelled at football and basketball, and he dreamed of playing in college. The future seemed full of possibilities.

Keegan's biological father wasn't much in the picture. He went to prison for selling drugs before Keegan was born, and Sharon always imagined their relationship, maintained mostly through letters and the occasional phone call, caused internal anguish with her son. There was also the matter of growing up biracial — Sharon is white, Keegan's dad is black — and Keegan often being among a minority of children of color in school.

When Keegan was 7, Sharon married Paul Coe, a white man. She tried to find a black role model for her son by enrolling him in Big Brother programs, but they were always placed at the bottom of the waiting list, she remembered.

Keegan started getting in trouble in middle school. One semester, his principal suspended him 11 times for mouthing off and arguing with teachers. Sharon realized her son was hanging out with gang members, so she moved him to different schools around the city, but trouble followed to each one. In high school he was convicted of possessing prescription pain pills. Because they lived across from a school, the prosecutor upped the charge to a felony, ruling out a career in teaching or social work, like he'd always talked about.

Keegan graduated from Washburn High School in 2010, and Sharon thought he had finally outrun his problems with the law when he moved two hours west to Willmar, Minn., to attend community college and play basketball.

But the real problems were just beginning.

Keegan was less than a year from finishing his associate degree when he called from the Hennepin County jail to say he'd been arrested in connection with a drive-by shooting.

No one was hurt, but the incident came just weeks after the high-profile death of Terrell Mayes, a 3-year-old shot by a stray bullet, and prosecutors charged Keegan with eight felonies, including drive-by shooting and second-degree assault. Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman made an example out of the Rolenc to the press, identifying him as a member of the Tre Tre gang and linking the assault to the same pattern that caused the Mayes killing.

"You can't make a priority of every single one of the 10,000-plus crimes that come in here," Freeman told reporters. "But when you look at the ones that we believe — and history shows us — cause the most misery in the neighborhoods, I think it's guns. And it's gunfire that tragically killed [Terrell]."

Isolation takes hold

Winter has come, and the ACU is cold. Rolenc sits under three blankets, and his nose is still running. He's so hungry he eats a sugar packet. He starts sleeping until 2 or 3 p.m., sometimes as late as 9.

Rolenc misses his son. He feels utterly alone.

He calls Shay. Her lip is badly split and she might need plastic surgery. She doesn't accept his apology. She doesn't care that he got a year in the hole. Their son has been talking about the time Daddy punched Mom.

Writing in his journal later, Rolenc can't find the words to describe how that makes him feel. He wants to tell Jamaal that what he did was wrong, and that no man should ever put his hands on a woman.

I need to find other ways besides violence and intimidation to get what I want, he writes.

Rolenc's 360 days will be broken up into phases. Phase one means he gets five books and one phone call a week. With good behavior, he'll hit phase three in March, and he will be allowed more phone calls and snacks from the commissary. Maybe even a radio.

He tries to make the best of the time. He starts reading "Waiting to Exhale" by Terry McMillan and books about travel and starting a small business. He resolves to go to back to school when he's out. Maybe he can be a lawyer or paralegal. During the weeknights, correctional officers leave the exterior cell door open, and Rolenc stays up all night playing chess with his cell neighbors by tearing pieces of paper, drawing a board and shouting out moves.

In January, his son finally comes to visit with Rolenc's mother, Sharon. He hasn't felt this good since he arrived into solitary. Jamaal tells him that whenever the phone rings he rushes to pick it up, thinking it's his dad, but it never is.

I told him I wish I could call every day but they only let me once a week, but that I think about him every day all day. Man I miss my lil dude. That's my life.

A mother's dread

Sharon is dismayed that Keegan struck the mother of his child, and doesn't question that he should be seriously disciplined for it.

"What I question is the use of solitary," she said.

When Keegan told her about his sentence, Sharon had read articles about other states rethinking the use of solitary confinement. She was shocked that Minnesota still gave out yearlong terms, she said. She found herself overcome with fear about who would come out of that cell after 360 days of solitude.

"I worry about what solitary is going to do — to destroy that spirit," she said. "That passion in him. That fierce protectiveness. That social animal. That kind, loving, big-hearted young man. What's it going to do to him?"

Sharon started calling and e-mailing corrections officials, and state and local politicians, pleading for an amended punishment that didn't carry the potential mental health effects of solitary.

"Please do something," she wrote to Gov. Mark Dayton. "Say something. If you remain silent, how will this ever change?"

"I'm back to sleepless nights, worried to death that my son will be ignored when he needs help the most," she wrote in another. "I'm back to being terrified that I will get a call that my son has died in his cell, either due to something that was 100 percent preventable, or at his own hands because the DOC officers have done everything in their power to break him down. Please, please don't let that happen!"

"There is absolutely nothing in his record to justify a year's worth of solitary confinement," she wrote to Bruce Reiser, deputy commissioner for the Department of Corrections. She understood the department extending Keegan's prison sentence, she wrote, "but 360 days in solitary? No programming, no job, no classes? He's released from solitary a month before he's released from jail. How on earth does this prepare him to succeed after prison? How does this 'contribute to a safer Minnesota' as the DOC website's tagline says?"

Reiser assured her that he was aware of the mental health concerns of solitary, and the department would assign a therapist to keep an eye on him. But Keegan committed a serious offense, he wrote, and the department's discipline policy was clear.

"I encourage you to speak with your son in regards to what he can do to better himself while he is incarcerated," he wrote.

Monotony

Rolenc wonders if there's a ghost in his cell.

He wakes up in the middle of the night and finds a light has turned on, even though the switch is across the room. He gets up and turns it off. As soon as he falls asleep he hears a loud noise. This time an orange has fallen off his sink onto a garbage bag.

Yeah there's a ghost or something in here, he concludes. He hopes no one died in his cell.

He has stopped getting out of bed, other than for meals. He reads the same books over and again. He frequently hears men screaming down the hall. One day someone is threatening to kill himself.

He gets so frustrated he contemplates a violent episode, but he decides he needs to be more tactical.

I'm a prisoner of war behind enemy lines right now, so I need to think and act like it. They got the upper hand right now so it's cool, I'll have to play the hand I was dealt and hold my cards to my chest.

He thinks always of Jamaal. He doesn't want him to follow the same criminal path he did, but sometimes he wonders if it's too late.

One night he dreams Jamaal transforms into water, and Rolenc has to carry him in a plastic bag. He steps outside into a hurricane and the bag spills. When he gets back inside, too much of the water has gone, and it won't turn back into his son.

A couple of days later, a correctional officer tells Rolenc they're taking away his visits. Rolenc was never supposed to get them, he says. There was a mistake at the head office. This means Rolenc won't see his son until he gets out in nearly a year.

He feels his heart pounding. His head throbs and his hands shake. He wants to snap. Instead, he lies down and prays not to do something he will regret.

Over the next few days, he lies in his bed and imagines what it will be like to get out and see his son. He can't sleep and frequently wakes up in the middle of the night and lies there until breakfast.

I think I'm losing my damn mind, he writes.

Rolenc has lost 23 pounds, he writes. He feels his body is falling apart.

A neighbor advises Rolenc to eat his own feces. He says that will buy him a transfer out of ACU and into the mental health unit, where the food is better. The inmate says he's going to eat his feces every day until they transfer him.

"You got a chemical imbalance," Rolenc tells him.

"You gotta do what you gotta do," his neighbor replies.

Rolenc thinks about the outside. His life has been on pause since he came to prison in 2012 — when he was 19 — but the rest of the world has remained on play. He tries to imagine how his friends and family have changed, but he can't. He sees them only as they were four years ago.

One day he gets a letter from his father saying he's back in prison, too. He thinks again about Jamaal and the toll of growing up with family members in prison.

So I question myself if at the tender age of five my son has already been stripped of his idea of a loving, caring, carefree world?

And if that is true, he wonders, is it his fault?

Spring, and a threat

March 1. Rolenc learns that the Rice County prosecutor is charging him with third-degree assault for beating up Shay. If convicted, he could spend two more years in prison — on top of the one-year that he's serving in solitary, and in addition to the 120 days that were already added to his sentence.

That means two more years of missed birthdays, holidays, basketball games.

He loses his temper. He thinks the charge is unfair on top of the punishment he's already serving. He resolves that he won't take it idly.

I'll tell you one thing, I'ma wild the f*** out when I get there, he writes. That's on everything I love — even if that means spending the entire sentence in solitary.

The days feel different now. He thinks only of what he will miss. He talks to himself, holds entire conversations by acting out both parts, and wonders if he's going crazy or if he's always done this and never noticed.

One night he wakes up and everything is wrong. The cell looks like a funhouse. He screams and begs for it to stop. He considers hitting the panic button and fighting the officers when they arrive, but he resists.

Some relief comes when he finally reaches phase three, which allows him to load up on cookies, crackers and Cheetos until he's full for the first time in months. He's allowed more books and starts reading Homer's "Odyssey," "Night" by Elie Wiesel and a biography of black playwright Lorraine Hansberry. He's moved most by Hansberry's story, and saddened that she died at 34. He wonders what she would think of race relations in the world today.

I am glad she lived, he writes.

He sees the moon outside his window for the first time in months and stares at it until his eyes burn. He wonders how the Earth must look from the moon. He thinks about the arrangement of the cosmos and how if one thing fell out of place the human race would be wiped out. The delicate balance makes him wonder how some people cannot believe in God.

I think it's pretty clear that there is a god, he writes. Personally I've been spared and Blessed too much not to believe.

He gets a radio. He hears on NPR that the U.S. Treasury might put Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill. He can't believe it — a former slave on American currency! It makes him think about his own ancestry. My great great great grandparents were slaves. Great great grandparents the children of slaves. It's in the bloodline to survive.

In May, He reaches the halfway point to his solitary sentence and talks to Jamaal on the phone. Shay has told Jamaal his dad will be home for Christmas. Jamaal says he wants some books, PlayStation 4 and a Spider-Man game.

He asks if Rolenc will have to go back to jail after Christmas.

Rolenc says no and hopes it's true.

As trial nears, anxiety and hope

On a late-summer evening, Sharon takes Jamaal to soccer practice. On the way, they stop for a snack at a gas station. Jamaal buys some candy and parades out of the store with the boundless energy of a 5-year-old.

"He skips and runs just like his father used to," says Sharon laughing.

They arrive at the soccer field, and Sharon straps on Jamaal's shinguards and cleats. The coach asks the parents to come help with drills, and Sharon fills in, running around the field trying to keep up with her grandson.

"I'm always the runner and I never get catched!" Jamaal announces proudly.

Sharon is trying to help Keegan find a lawyer to fight the new charges filed by Rice County. She first contacted a high-profile private attorney, but Keegan decided to turn instead to a public defender because the cost was so high. The trial is scheduled to begin this month.

Rice County Attorney John Fossum said his office doesn't treat charging decisions differently just because someone's already being punished in prison. "This was a pretty brutal, violent assault," he said.

Keegan's public defender, Erica Sutherland, called the charges excessive given that he was already punished with a year in solitary and an extension to his prison sentence. In an interview with Sutherland's investigator, Shay said she wanted the case dismissed, and agreed that the current punishment is severe enough.

Even if Keegan loses his case, there's a chance the trial could be postponed, meaning he would still get out of prison, if only for a month, on Dec. 20 — in time to spend Christmas with his family.

"That's the hope," Sharon said. "That's the hope."

In the meantime, Sharon is doing all she can to keep her mind occupied. She joins a second book club. She starts going to exercise classes almost every day after work. Still, the anxiety can be overwhelming.

While Jamaal runs drills on the field, she produces a note from Keegan that she found recently. He gave it to her on his own 18th birthday. "Happy Birthday," it reads, "for being with me 18 years into young adulthood and taking care of me."

A world within reach

Rolenc's looking at himself in the mirror. He catches the reflection of a correctional officer doing his rounds. He imagines what the officer thinks about. For Rolenc, prison has become normal. But for someone who's never served time, it's anything but normal. He tries to think objectively about walking through the halls of the ACU. It probably looks like a holding facility for animals.

It must have been a very cruel mind to come up with an invention such as this, he writes.

He longs for the distractions of general population: gym, phone, conversation with other inmates, regular visits from friends and family. He gets headaches every day for a week.

He talks to Shay on the phone, and they finally have an amicable conversation. It's taken a while, but he's relieved to feel like they've found a point of mutual respect.

Back in his cell, he hears other inmates yelling and kicking cells all night. He thinks about being free — a topic that frequently crosses his mind — but this time he's not imagining where he will eat first, or how he will surprise his son at home. Instead, he worries about jumping from prison back to the real world.

Does going home still feel the same when you haven't been there in years? he writes. I wonder if I will feel at home or if I'll feel like a stranger.

Outside his window, Rolenc sees three hot-air balloons flying overhead. One is purple, one is blue and one is black. He promises himself that next summer he will take a hot-air balloon ride, and he will fly over Oak Park Heights and look down to the ACU and reflect on the time he spent in the hole.

I'll think about my homeboys here at Oak Park and in Stillwater that got decades — or their whole life — to do behind bars. My heart will bleed for them.

I'll think about all of the brothers going through the struggle. Doing time. Sitting in segregation. Feeling like the world's against them ... Feeling like everyone has turned their back on them. I'll pray for them.

And I'll be humbled. And cherish the moment and my freedom. As I look down on where I came from — and where I'll never return to.

In prison, Mark Fenning was a brawler.

Sentenced to five years for driving while drunk, Fenning made it his mission to punish sex-offending inmates with his fists. Disagreements with correctional officers often turned physical, and sometimes didn't end until he was carried off in restraints.

Fenning got into so much trouble that he spent more than two years in solitary confinement.

He finally got out of isolation on a spring day in 2015, when he was released from prison onto the streets of Stillwater with nothing but a couple hundred dollars in his pocket.

"You go as you are," Fenning said. "They're done with you."

The transition from a prison cell to freedom can be perilous for any inmate, but those who've spent extended stays in solitary face an especially rocky path. Some come from strict lockdown units, where every detail of their lives is predetermined and monitored by prison staff. Many suffer from mental illness caused or made worse by days or even years of isolation. They've been denied prison jobs, educational programming and normal visits from friends and family — all of which have been proved by Minnesota Department of Corrections studies to reduce their chances of being rearrested. They also don't receive normal services designed to help them re-enter society, such as classes on job skills, staying sober or finding housing.

In the past six years, Minnesota prisons have released nearly 700 inmates directly from solitary back into society, according to DOC data.

Some, lacking fundamental social skills, simply fail to find their place in a society they no longer understand. Others turn back to crime and end up in prison again, not knowing any other way of life.

"You ever see bulls when they prod them in the bullpen? That's sort of what solitary confinement is," said John Turnipseed, an ex-Minneapolis gang leader who served 10 years in prison, including 18 months in solitary, and now helps former prisoners through the nonprofit Urban Ventures. "You get prodded and then they let you into society. I just think it's an inhumane practice."

Back to reality

Some inmates serve their entire sentences and hardly see the outside of a solitary confinement cell.

In summer 2013, Wayne Mathern was caught trying to cash phony checks in the name of a construction company and sentenced to more than a year and a half in prison. He was sent to isolation two days after his arrival, originally for disorderly conduct. He would serve his entire term there, save for 12 days, and leave prison directly from solitary confinement in May 2015.

FROM SOLITARY

TO SOCIETY

Within a week and a half of being free, he'd been cited twice for shoplifting. There are now three warrants out for his arrest for separate theft charges.

Research across the nation shows how serving time in isolation makes the already-difficult task of re-entering society from prison even harder. Studies in Texas, Washington and Michigan have all found higher rates of rearrests for inmates who spent solitary time.

A 2012 paper anchored by research from Arizona anthropologist Brackette F. Williams described the release of these inmates as a "recipe for failure." Inmates in a supermax unit — similar to the one in Minnesota's Oak Park Heights prison — came out "deeply traumatized and essentially socially disabled," she concluded.

In a high-profile incident in 2013, an inmate who was released straight from solitary shot and killed the head of corrections in Colorado. The incident helped fuel massive reforms, and now the prison system limits disciplinary solitary sentences to 30 consecutive days.

Given the high rate of mental illness among inmates serving time in solitary, releasing them without first giving them the treatment to help them succeed is like releasing a person with an untreated infectious disease, said Dr. Kenneth Appelbaum, a psychiatrist who oversaw treatment of inmates in Massachusetts prisons for a decade.

"Do you want them returning to the community without having those problems adequately addressed?" he said. "It puts the general public at risk."

Thrust into society

In Minnesota, inmates considered too dangerous for the general population of a maximum security prison one day are often thrust back into society the next, with nothing but workbooks and videos to prepare them for life outside.

Minnesota does not have the death penalty, and only 130 inmates out of more than 10,000 are serving life sentences without a chance of ever getting out, meaning most people who go to prison will one day get out. For this reason, over the past decade, the state Legislature has spent millions of dollars on programs to help prisoners transition back into society, find a job and stay out of trouble.

"We want them to be thinking of their release and their success upon release from the day they walk through the door," said Terry Carlson, deputy commissioner with the Department of Corrections.

But inmates who live long periods in solitary don't get the advantage of many of these services. While prisoners in general population spend months taking classes designed to help them succeed on the outside, inmates in solitary are deemed safety risks and not allowed to participate.

In recent years, the DOC has been paying closer attention to these inmates, Carlson said. The department has stepped up its efforts to identify them early and, "if it's feasible," move them back into a prison's general population before release, she said. In some cases, prison staff will offer one-on-one help.

But if the inmates don't cooperate or continue to pose a threat, they will remain in isolation until their last day. Last year, 71 such inmates left prison straight from solitary.

Carlson points to Minnesota's sentencing laws as one reason for this. Unlike New York and California, the vast majority of Minnesota prisoners do not leave through "parole" — the system in which a board decides when an inmate should be released based on evidence of rehabilitation.

Instead, Minnesota uses a system called "determinate sentencing," in which prisoners are expected to serve two-thirds of their sentences in prison, and the final leg under the supervision of a case officer in the community.

However, if the inmate misbehaves in prison, the DOC can delay their release without having to go to a judge. If prisoners rack up enough discipline, they can serve out the entire sentence in prison — including the final one-third — and the department legally has to discharge them with no community supervision.

Those last few months of transition classes are most critical to making it on the outside, said Turnipseed. Losing out on those services is compounded by leaving prison straight from isolation.

"I just think all of the hope gets beaten out of you in solitary," he said. "People can build that back up, but if you don't have the chance to do that, a hopeless individual walks out of the penitentiary not even knowing what's going on in the world."

'I kind of gave up'

On a summer afternoon in Montevideo, Fenning sits shirtless in a smoke-filled mobile home, showing off his hardened, wiry frame covered in so many tattoos he's lost count.

"That's the family cemetery," he said in an interview, pointing to an illustration of headstones on his leg, each one marking a lost loved one. The word "Outlaw" is emblazoned across his abdomen. He points to a scar on his forehead where he said he sliced himself with a razor blade in segregation when his request to transfer to a mental health unit was denied.

"My whole floor was bloody," he said.

Fenning, who lives with bipolar disorder, racked up 25 solitary confinement sentences from November 2010 to his release in 2015 for behavior like fighting, possessing a tattoo gun and making alcohol in his cell toilet.

"I started going nuts in there, man," he said. "More than I already was. I started cutting my family out. Every time I called [my wife] was a fight. I was talking about not even coming home — turning that five years into a life sentence."

His last stint in solitary was in a Stillwater prison unit called B-West. He was allowed an hour out of his cell each day to exercise with other prisoners, but that time frequently meant more fighting.

"It's wild," said Fenning — which is why inmates call this wing "The Wild West." "Every day there's fights."

Solitary changed him, he said.

He still sleeps during the day and stays up all night, a practice he picked up in segregation because the other inmates were noisy at night. He said he feels more hateful. He's lost all of his patience and simply doesn't care about things he once did.

"I don't have the go for life like I used to," he said. "I kind of gave up."

Since leaving prison more than a year ago, Fenning has struggled to get by. He and his wife first tried settling in a mobile home park in Oakdale, but they had to leave after Fenning started using methamphetamine. They spent much of the winter living with two dogs in a van with a broken heater. In June, they finally scraped together enough money to rent a mobile home.

"We've had a lot of bad luck," he said. "She ain't working right now, I ain't working. We haven't even made rent this month yet. We've got a lot of stress going on."

In September, Fenning was arrested for driving without a license and possessing a small amount of marijuana, and now faces gross misdemeanor and misdemeanor charges. He was evicted from his mobile home for not paying rent. He's back living in his van, trying to get by, trying to stay sober, trying to find a home for himself and his wife and — above all — trying to stay out of prison.

"When I got out — she thinks something dark followed me home," he said.