Nearly a dozen residential treatment centers for children with serious mental illness have lost millions of dollars in federal funding, the result of a federal policy that could imperil care for hundreds of Minnesota youths.

After a prolonged review ordered by federal officials, state regulators determined last week that 11 treatment centers with a total of 580 beds no longer qualify for coverage under the federal-state Medicaid program. Officials cited a 1960s-era rule that prevents Medicaid from paying for care at institutions with more than 16 beds.

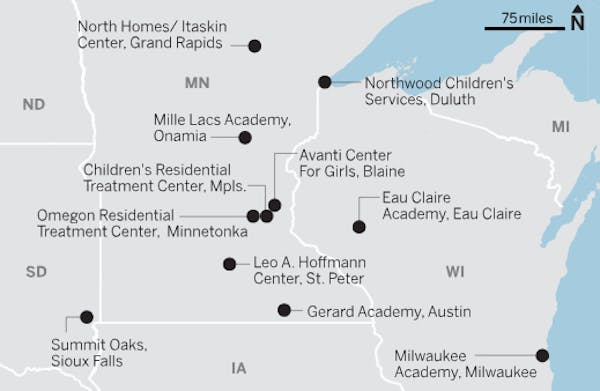

The decision casts doubt on the future of residential programs, spread from Austin to Duluth, that treat hundreds of children and adolescents who have histories of trauma and suffer from a range of psychiatric problems, including severe anxiety and self-injury. State officials and mental health advocates say the facilities are vital to helping children return to stability after psychiatric crises, in addition to avoiding costly treatment in hospital settings.

Related

Looking at federal funding cuts

Unless state legislators step in to provide stopgap funding, the treatment centers would lose about $4.5 million in annual Medicaid funding, and would be forced to rely on county governments for support — a prospect that is far less certain, officials said. Some of the facilities might be forced to close or reduce their services, officials said.

"These programs are crucial," said Claire Wilson, an assistant commissioner at the state Department of Human Services (DHS). "We have limited capacity right now, and we know we have kids being sent all over the state, and sometimes out of state, for residential treatment."

The Medicaid decision marks the latest setback in the state's efforts to expand mental health treatment for the estimated 109,000 Minnesota children with serious mental illnesses. Last month, city leaders in Forest Lake rejected a proposed 60-bed psychiatric facility for children and teenagers, despite overwhelming support in the community.

In addition, Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis plans to close its residential treatment program at St. Joseph's Home for Children in Minneapolis by August, officials with the nonprofit said Tuesday. The program has 30 beds and each year serves 60 to 70 youths with mental health and behavioral problems. And last year, the troubled St. Cloud Children's Home, a 60-bed treatment center operated by Catholic Charities of the Diocese of St. Cloud, shut its doors after state regulators cited it for repeatedly failing to protect young patients from harming themselves.

Even before these closures, Minnesota families reported struggling with a shortage of treatment options for children with severe mental disorders. Across the state, children needing psychiatric care have wound up cycling through hospital emergency rooms or going out of state for treatment. Statewide, roughly 300 children go out of state every year to receive this level of care, according to the DHS.

"Where are all these children going to go?" asked Sue Abderholden, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) of Minnesota. "Families don't have the resources or services to keep their children safe and to help them get better."

'We need more options'

The decision reflects a decades-old federal policy against paying for treatment at large institutions. The policy stems from the 1960s-era movement to deinstitutionalize care for people with mental illnesses and developmental disabilities, amid concerns about the cruel and inhumane treatment of people in large state mental hospitals. To encourage treatment in the community, Medicaid prohibited reimbursements to certain mental health facilities with 16 or more beds, a provision known as the "Institutions for Mental Disease exclusion."

Since 2001, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency that oversees Medicaid, has allowed Minnesota to receive federal matching funds for children receiving care in residential treatment centers. However, after the CMS ordered a review, the Minnesota Department of Human Services reclassified these facilities as "Institutions for Mental Disease" because they have more than 16 beds.

"The struggle for Minnesota is that we have not built up a very robust treatment system" for children, Wilson said.

Without Medicaid funding, many of the residential facilities would struggle to stay open. At Northwood Children's Services, which operates a 44-bed residential treatment center for children in Duluth, up to two-thirds of the patients are eligible for Medical Assistance, the state Medicaid program.

"If there would be no alternative funding found, it would put us in serious jeopardy — there's no question," said Richard Wolleat, president and chief executive.

For now, the decision will not immediately affect children and their care. That's because the 2017 Legislature authorized funding to cover the residential treatment programs until April 30, 2019. However, without further action, counties would be responsible for the full cost of the services when the state funding expires, officials said.

It remains unclear if county governments will be willing to step in.

Eric Ratzmann, executive director at the Minnesota Association of County Social Service Administrators, said the extra costs would pose "a significant challenge" for county governments; some might choose to provide care in more community-based settings than the residential treatment centers.

"This is a reminder that we need to broaden our system of care for our children," Ratzmann said. "We need more options."